Supported by a Create NSW Arts and Cultural Grant – Old Parramattans

WARNING: This essay discusses child abuse, which may be distressing for some readers. Reader discretion is advised.

Parramatta Burial Ground, Saturday 7 January 1804

A convict thrusts a shovel into the fresh grave of little Mary Grimshaw, and tosses the soil aside. There have been whispers of foul play, and the surgeon, D’Arcy Wentworth will not rest until a full examination allows him to either confirm or allay his worst suspicions. The pile of earth beside the grave grows higher, till at last the five-year-old’s body is exhumed and back among the living.

It is now Surgeon Wentworth’s turn to do the digging; to open up her earthly remains and uncover what is lying beneath the skin, bone and tissue. His late patient is something of a whited sepulchre herself, for he is convinced that, deep inside, this innocent one is unwillingly keeping the rotten secret of her own father’s ‘merciless’ violence.[1]

The Father Grim

The chief suspect in what appeared to be Mary’s wrongful death was her father, Richard Grimshaw, a convict who had arrived just ten months earlier on the ship Glatton (1803).[2] Although he was a transported felon, Grimshaw does not seem to have been a career criminal by any means. Indeed, unless he had been very good at avoiding capture in any earlier illegal shenanigans, his life up until mid-1801 followed a tried and true progression down the path of civility.

Born in Heckmondwike, Yorkshire, around 1768, Richard Grimshaw was the son of Abraham and Dorothy Grimshaw (née Preston), and was about twenty when he married Mary Langfield, a young woman of his own parish.[3] The couple did not venture far from their native place, but established themselves in nearby Lowtown, Pudsey, Yorkshire, where Richard worked as a labourer and Mary gave birth to their five children: John (b. 2 June 1789), William (b. 13 June 1791), Thomas (b. 18 May 1795), Mary (b. 7 June 1798) and Elizabeth (b. 17 January 1801).[4] The Grimshaw children were all baptised at St. Cuthbert’s, Ackworth, in the borough of Wakefield, even though the eldest two children’s baptism registrations incurred a fee of three pence each following the Stamp Duties Act of 1783 (23 Geo.III, c.67), which was passed to help fund the war against the rebellious American colonists in their ‘Revolutionary War.’[5] Many parishioners simply deferred baptism until the act was repealed in 1794, so it says something about Richard’s own religiosity and dedication to his children’s spiritual welfare that he, a humble labourer, readily paid the fee. By the time the Grimshaws’ fifth child, Elizabeth, was born in January 1801, the family had moved to Moor Top, which was closer to Richard’s birthplace of Heckmondwike, and if a newspaper report is correct, Richard was then ‘a private in the 3d Regiment of Foot Guards (later known as the Scots Guards).[6] The Grimshaws’ youngest child was a mere five months old and not yet baptised when both Richard and Mary were tried at the York Assizes on 18 July 1801 for burglary.’[7] Mary must have been found innocent of the charge, because only Richard was convicted and sentenced to hang.[8] Fortunately for Richard, ‘[b]efore the Judges left York,’ The Morning Post reported to its readers on 3 August 1801, ‘they were pleased to reprieve Richard GRIMSHAW’ and five others ‘in the castle,’ a decision which saw Richard’s death sentence commuted to fourteen years transportation.[9]

When the youngest Grimshaw was baptised at the family’s parish church a couple of weeks later, Richard was confined on a hulk moored in Portsmouth Harbour: the Captivity.[10] In a former life, the Captivity hulk had been the Royal Navy’s 64-gun third-rate ship of the line HMS Monmouth (1772) and had seen action in the American Revolutionary War before being renamed the Captivity and repurposed as a floating prison in 1796. The Captivity was ‘newly fitted up for [the convicts]…under regulations recently adopted, for better promoting the health, increasing the accommodations, and establishing good order and discipline among the Prisoners.’[11] During Richard’s time on board this hulk, Sir Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild inspected it thoroughly for the purposes of writing their ‘Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802.’[12] Their ‘general inspection of every part of the ship’ revealed ‘that all possible precautions were taken, to ensure cleanliness and proper ventilation, and to afford every convenience to the men that could be expected, where so large a number are confined in so small a space.’[13] In fact, ‘a new Chapel’ had even been ‘lately constructed, in the middle of the ship, sufficient in size to admit the whole complement of Prisoners at once,’ although a ‘regular Chaplain’ had not been appointed to perform Divine Service in it.[14] The authors of the report were also satisfied that there was a sufficient allowance of diet and that the quality of the provisions on board were likewise satisfactory; they ‘could not however avoid remarking, that the Convicts generally…are supplied with no vegetables whatever, but such as they purchase themselves.’[15] If Richard managed to stay ‘robust and healthy’ in these conditions, he would have been ‘employed out of the ship, in his Majesty’s Dock-Yard.’[16] On the other hand, Richard may have been one of those who were unable to work ‘in consequence of sore legs,’ which the surgeon attributed to ‘an impoverished habit, and the want of proper care, during their confinement in those Gaols whence they were sent to the Hulks.’[17]

Almost thirteen months after Richard’s conviction, the convict ship Glatton left the Downs and reached Portsmouth on 31 August 1802, in readiness for its voyage to the Colony of New South Wales.[18] By 4 September, the Glatton was lying at Spithead, and Richard—along with another 269 males and 130 females selected from among the transportees for this particular journey—were embarked from various hulks.[19] Unlike many convicts who left their families behind, Richard’s wife and two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, who were then four and two years old respectively, were among the 30 to 40 people who were also making the journey aboard the Glatton as free passengers.[20] The Grimshaws’ three sons, then aged between seven and thirteen, remained behind in Yorkshire.

The Glatton sailed from England on 23 September 1802, and its 169-day voyage to New South Wales seemed to be quite a success medically speaking, especially compared to earlier crossings.[21] ‘By means of air-tubes and other contrivances, together with due attention to cleanliness and diet,’ fever and flux had been avoided, so there was no loss of life due to shipborn diseases or accidents; the seven convicts who passed away during the voyage had instead died from ‘chronic disorders.’[22] All the same, as the Sydney Gazette recorded, ‘The day before [the Glatton] got into the Cove’ on 12 March 1803, ‘100 weak people were taken out, and put on board the Supply, 50 of the most ailing were soon after sent on shore to the General Hospital, where every attention was paid them. Their complaints were slightly scorbutic,’ meaning they were showing the early signs of scorbutus (scurvy), a severe vitamin C deficiency.[23] Based on James Lind’s description of the progression of the illness in his Treatise on the Scurvy (1757), these early signs would have included:

a change of colour in the face, from the natural and usual look, to a pale and bloated complexion; with a listlessness to action, or an aversion to any sort of exercise. When we examine narrowly the lips, or the caruncles of the eye, where the blood-vessels lie most exposed, they appear of a greenish cast. Mean while, the person eats and drinks heartily, and seems in perfect health; except that his countenance and lazy inactive disposition, portend a future scurvy. This change of colour in the face, although it does not always precede the other symptoms, yet constantly attends them when advanced. Scorbutic people for the most part appear at first of a pale or yellowish hue, which becomes afterwards more darkish and livid.[24]

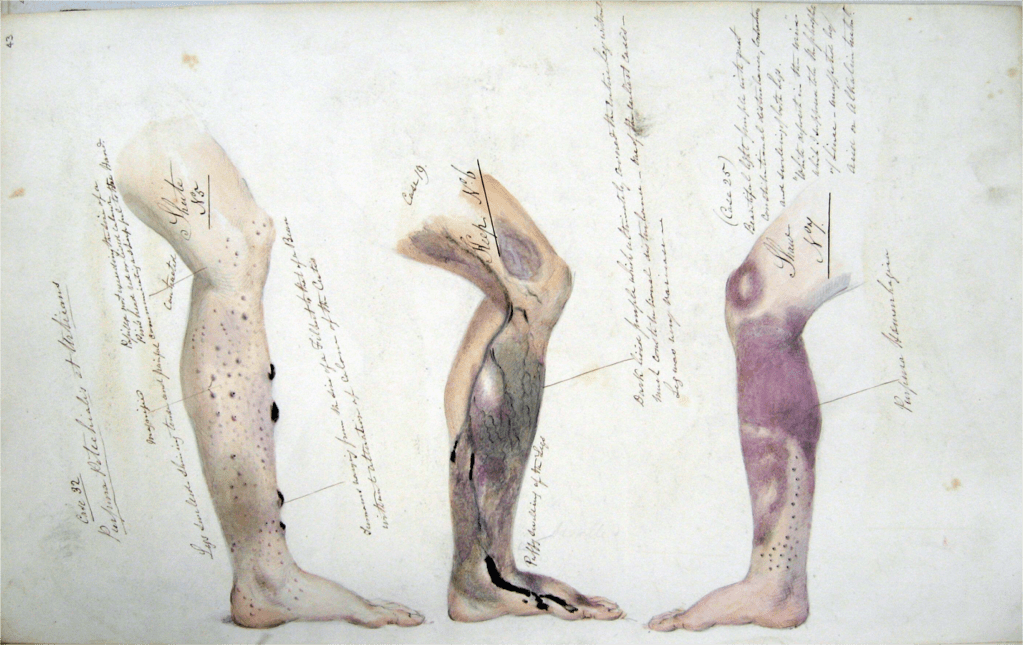

Image: Karl Heinrich Baumgärtner, “Scorbut, Scorbutus,” Physiognomice Pathologica, (Stuttgart: 1839). Courtesy of The Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, Stockholm.

As Richard Grimshaw and the other prisoners who had been held on the hulk Captivity had already had ‘no vegetables whatever, but such as they purchase themselves’ for months prior to the voyage, many of them would have been among those showing these scorbutic signs; indeed the ‘sore legs’ some of those on the Captivity hulk complained of prior to transportation was also likely the onset of scurvy.[25] Yet scurvy would not have struck the Glatton’s convict passengers exclusively. Since it only takes between one to three months of continuously limited or no vitamin C intake in a person’s diet before scorbutic symptoms present, and all passengers had limited or no access to fresh fruit and vegetables during the lengthy sea voyage, free people on board were equally at risk of developing this debilitating and potentially fatal illness. It is probable, therefore, that Mrs. Grimshaw and the two young Grimshaw girls, Mary and Elizabeth, were among the 100 who required varying levels of urgent medical intervention for this malady upon arrival in the colony.[26]

Scurvy was treated by providing those affected with a diet rich in fresh ‘summer-fruits of all sorts’ including ‘oranges, lemons, citrons, apples,’ and fresh ‘green herbage or wholesome vegetables,’ all of which contain vitamin C.[27] Even in the more severe cases, wrote Lind, ‘the first promising appearance’ following the reintroduction of fruit or greens ‘is the belly becoming lax; these having the effect of very gentle physic: and if in a few days the skin becomes moist and soft, it is an infallible sign of their recovery; especially if they bear gentle exercise, and change of air, without being liable to faint. If the vegetable aliment restores them in a few days to the use of their limbs, they are then past all danger of dying at that time of this disease.’[28] Thus, the Sydney Gazette was not being overhasty when it reported only one week after the Glatton’s arrival that the 100 scorbutic cases ‘are recovering very fast,’ for while scurvy was an horrific and potentially fatal illness, it was also a preventable and curable one.[29]

Scurvy or no scurvy, thirty-five-year old Richard Grimshaw was in the prime of his working life as an experienced labourer, so it is not surprising that the authorities wasted no time in sending him up river to work off his sentence in the colony’s second mainland settlement, the young, developing town of Parramatta in Burramattagal Country. We can infer this movement inland soon after the Grimshaws’ arrival from a newspaper report, which reveals that by late September, a little over six months after the Glatton dropped anchor, the family were already settled in and living at Parramatta together in a ‘house,’ that is, a convict hut, which they shared with fellow Glatton convict Thomas Greensmith.[30]

By the time Mary Grimshaw turned five years old at Parramatta on 7 June 1803, then, she had already experienced a significant and continual amount of upheaval that even an adult would have struggled to process. She had been separated from her father for almost half of her life during his incarceration and transportation, during which time she may have experienced some level of poverty; consequently, she had been removed from her country and from the company of her elder brothers and extended family; she had sailed the high seas and endured all that came with it, including the constant damp, sea sickness, and a want of fresh food which then more than likely led to a bout of scurvy; she had found herself in a new land with an exceedingly different climate to the one she had known; and she was having to adjust to living in a small hut not only with her estranged father again but also with a male convict who was not a family member. In addition to all this, we can only imagine what emotional distress the child was likely privy to in that small convict hut; after all, her father had been a free, labouring man in Yorkshire, but after doing whatever necessary to survive incarceration in England, his transportation as a convict, and his ongoing experience as a forced labourer who was stripped of his dignity and freedom, and subject to harsh, degrading punishments in Parramatta, he could hardly have been the same man. Then there was Mary’s mother, who was no doubt much changed by the traumatic events of the last couple of years. In Yorkshire, she had been surrounded by her entire family, but having left three of her children behind as well as all the familiar faces and places of the parish in which she had lived her whole life, she was likely suffering depression, homesickness, and perhaps guilt that her actions might have reduced them to this, since she had been implicated in the crime that led to her husband’s conviction. Mary would have absorbed a lot of this darkness around her, even if she did not fully comprehend it. In the wake of all that had transpired, frankly it would have been strange if Mary had not misbehaved.

One Monday afternoon in late September 1803, Mary allegedly did act out in some way.[31] What naughtiness the little girl exhibited (if any) is not recorded; however, according to the story told later, in the eyes of her father she was guilty of some misdemeanour that was worthy of correction, and Greensmith, who arrived home in time to observe what followed, did not disagree.[32] Richard promptly fulfilled what was then widely considered part and parcel of his patriarchal role: he took ‘a few twigs out of a broom with the thick ends of which he gave [Mary] several smart strokes on the neck, shoulders, and arms; he also struck her on the side of the head with his open hand,’ and the child ‘reeled.’[33] Warranted or unwarranted, the punishment must have been efficacious, because according to Greensmith, Mary apparently stayed out of trouble. The members of the household went about their lives as usual for the next couple of months, and the reportedly isolated, unpleasant episode might have eventually been entirely forgotten by all and sundry were it not for some troubling and inexplicable afflictions with which little Mary suffered as the year of 1803 waned.

Parramatta surgeon, D’Arcy Wentworth, first visited Mary in late December when the child was ‘labouring under a very violent fever, which,’ he stated, ‘he [could] not then attribute to any particular cause, as the child made no complaint whatever.’[34] Even as the cause of the fever at that time eluded him, the surgeon proceeded to treat the fever itself, ‘administer[ing] such remedies as were generally found most useful in such cases.’[35] On 2 January 1804, however, the surgeon was again examining his young patient, who continued to decline, and ‘perceived a morbid swelling at the back of the neck, extending to the left ear.’[36] Alarmed at this discovery, Wentworth immediately made ‘some essential enquiries’ at which time ‘he was told by the mother that it must have proceeded from some violent treatment given some time since’ by the child’s father, Richard Grimshaw.[37] Upon ‘minutely examining the tumour,’ Wentworth became ‘conscious of the child’s approaching dissolution, and therefore did not think proper to open the skull,’ that is, to evacuate the subdural haematoma by performing trepanation, a grisly operation considering its method of drilling into the head of the fully conscious patient, as this was before the age of anaesthesia.[38] ‘[T]hat operation,’ Wentworth quite rightly acknowledged, ‘could only have tortured [the child’s] latter moments, without any possibility of prolonging the existence of the patient.’[39]

As Wentworth sadly predicted, death came to collect five-year-old Mary Grimshaw only two days later on 4 January 1804, and she was buried in the Parramatta Burial Ground (St. John’s Cemetery) the following day—although, as we know, she would not rest there for long.[40] Having gone to the trouble of having her body exhumed on 7 January, the surgeon proceeded with the trepanation he had not been prepared to perform on Mary while she was still living.[41] He ‘perforated the skull’ and was met with a large gelatinous bloody mass (the subdural haematoma), which is typically associated with a traumatic brain injury, that is, a blow to the head strong enough to burst blood vessels.[42] Since typically only a major assault, a bad fall, or some other equally catastrophic accident could do such damage, the surgeon ‘was decidedly of [the] opinion’ ‘that the child had received a violent blow on the affected part, which, from the appearance he could entertain no doubt whatever, had finally terminated its existence.’[43] And he had heard it straight from the mouth of the babe’s own mother: the child had received ‘some violent treatment’ from her convict father.[44]

Wilful Murder?

‘[F]rom the evidence that appeared before the Coroner,’ reported the Sydney Gazette, ‘a Verdict of Wilful Murder was returned against the father of the child, who was in consequence fully committed to His Majesty’s Gaol at Sydney, to take his trial for the offence before a Court of Criminal Jurisdiction.’[45] Thus, on 13 January 1804, a mere two-and-a-half years or so since he was sentenced to death for burglary, Richard Grimshaw was again standing before the court, ‘charged with Violently and Inhumanly Beating his Infant Daughter, Mary Grimshaw…and thereby giving several mortal Bruises, on the 26th day of Sept. 1803, which were the Cause of her Death upon the 4th day of January, 1804.’[46]

The surgeon, D’Arcy Wentworth, shared his findings with the court first, informing them of how Mary had declined over the ten days she was in his care, the results of the postmortem he conducted, as well as the information he had gleaned from Mrs. Grimshaw, who had thought the punishment Mary received from her father in September could be the only likely explanation for what proved to be her fatal injuries.[47] The court, however, quickly identified a number of problems with Wentworth’s theory. To begin with, they questioned the surgeon as to ‘whether he could positively aver that the tumour had originated from a blow.’[48] Wentworth confirmed ‘that such was his opinion,’ yet he had to concede that ‘as he did not see the child until about ten days before its dissolution, he could not pretend to speak positively, though such cases very rarely occurred without some previous cause.’[49] The court then expressed doubts over the significant delay between the date of the alleged violent assault and the child’s demise, asking Wentworth ‘whether it was a probable circumstance that a violent treatment sustained by a patient in the month of September should be the actual cause of her death at so distant a period.’[50] Nevertheless, Wentworth was not to be shaken from his belief in Grimshaw’s guilt. Summoning all his powers of persuasion, Wentworth declared that ‘in the course of his practice in this Colony, two instances of the same nature had come within his observation, in one of which the patient had survived a mortal injury 91 days, and in the other 93; in both [of] which it had been thoroughly ascertained, that death was the actual consequence of the injury, though after so considerable an interval.’[51]

The question, then, was whether anyone who had witnessed the allegedly violent interaction between the father and the child could verify that the chastisement was severe enough that the injury sustained could prove fatal months later. To this end, Greensmith was ‘duly sworn and strictly interrogated.’[52] He described the punishment he witnessed, admitting he had seen the open-handed blow to the child’s head, but tempering this by carefully pointing out that it had not even been ‘with sufficient force to occasion her falling, though she reeled,’ let alone to cause her to die from it months later.[53] Importantly, Greensmith added that,

no mark of violence whatever appeared, nor did he then or since conceive that the chastisement was in any respect severe, nor did he ever hear the child complain of any ailment for sometime after, tho’ he living under the same roof, was in the habit of seeing it frequently throughout the day. The child, he added, was always rather weakly; and although resident in the house, and in habits of intimacy both with the father and master, [he] had never seen it receive a blow before or since….[54]

At such a remove and with so little information, the value of Grimshaw and Greensmith’s opinions about whether Mary misbehaved, whether her punishment fit her crime, and whether the corporal punishment administered was actually mild or severe cannot be objectively assessed. Still, we might recall the sheer fact that both were convicts and, as such, they had experienced and witnessed a great deal of physical abuse themselves: it cannot be ruled out, then, that both men may have had a considerably distorted view about what constituted reasonable physical force against others. It could be that neither of them saw anything wrong with an angry, full grown man physically assaulting a small child, perhaps through no fault of her own but merely because she was ‘his’ and, as such, could be used as ‘a whipping post’ or outlet for her father’s own emotional turmoil as he wished. Greensmith’s revelation that the child was ‘rather weakly’ in general only made any physical punishment she experienced at her father’s hands all the more abhorrent. Moreover, how could anyone be certain that it was an isolated incident? No one was denying that Richard physically punished the child, thus establishing a history of this type of parenting. Richard might have beaten Mary more severely on another occasion, much closer to the time of her death, without her mother’s or Greensmith’s knowledge; after all, as Wentworth could not help but notice, the position of the ‘morbid swelling’ had been in the same region the father had been seen hitting the child in September: it was like a fingerprint or a signature. Then again, it is worth considering that it might not have been Richard at all: he did, in fact, solemnly ‘declare…his innocence of the Charge.’[55]

So, if not Grimshaw in September, might someone else have assaulted the child at a later date? There were two other adults who had the greatest opportunity. It is feasible that Greensmith, who had no familial connection to the small children with whom he was living, could have taken it upon himself to issue some corporal punishment of his own on some other occasion when Mary irritated him and, not knowing his own strength, took things too far. We may even cast an eye of suspicion towards Mary’s long suffering mother who had endured a great deal of heartache—had she at last reached breaking point? She had been rather eager to connect her husband’s actions with what had developed into a serious malady—were those the words of a guilty woman trying to deflect attention away from herself? Or had the little girl simply fallen over while no one was looking and, in her shock at the severity of the impact, gotten up and carried on as though nothing had happened? In all of these alternative explanations, the location of Mary’s subsequent ‘morbid swelling’ may have been covered up by her hair for some time and, thus, could have gone unnoticed by other members of the household until the surgeon inspected her two days prior to her death.

Evidently, there was nothing straightforward about this case. Thus, while D’Arcy Wentworth had been thoroughly convinced by his own theory of the child’s demise, the court proved less so. ‘[A]fter a short deliberation,’ Mary’s father Richard Grimshaw was ‘Acquitted’—and it was just as well, because it may be that it was never so much a question of who killed Mary Grimshaw, but what?[56]

A Patient and Deceitful Killer

Of all the things offered to the coroner and court as critical pieces of information in this case, the most important evidence could be Greensmith’s passing comment that Mary was a ‘rather weakly’ child.[57] Let us cast our mind back to the Grimshaws’ arrival in the colony, ten months earlier, when the Glatton arrived with passengers suffering from scurvy.

There is no surgeon’s journal for the Glatton voyage, so we will not conveniently find Mary’s name on a sick list with the word ‘scorbutus’ written next to it. However, as previously noted, there is good reason to believe Mary was labouring under the condition on arrival; after all, the scorbutic presentation of such a significant proportion of the Glatton’s largely adult passengers suggests that if adult constitutions could not even hold up against scurvy on the extended sea voyage, a growing four-year-old girl with a disadvantaged background had little hope of remaining healthy when she could not access fresh fruit and vegetables either.[58] Given how difficult it was to detect scurvy, though, if Mary was in the early stages of the illness on arrival in the colony, any slight symptoms she had might have been mistaken for something else, or she may have been relatively asymptomatic and overlooked altogether, so it is possible that she was not among the 100 transferred to the Supply or the 50 critical cases hospitalised and given a steady supply of vitamin-rich foods to treat the deficiency at all.[59]

Even in the best-case scenario that Mary received a correct diagnosis and treatment for scurvy when the Glatton docked, her prognosis would not have been great. Despite the Sydney Gazette reporting on the speedy ‘recovery’ of the Glatton’s scurvy sufferers, as with many qualitative and quantitative reports of morbidity and mortality on ships in the colonial era, the report written just one week after the ship’s arrival only tells us of the short-term statistics and positive results the patients in the hospital showed to the reintroduction of vitamin C-rich food in their diet.[60] The Sydney Gazette report could not reflect on the long-term suffering or even deaths that may have been at least partly attributed to this specific period of malnutrition. For example, in general, convict ship death statistics only tell us who died on the voyage and on arrival. As the St. John’s, Parramatta burial register attests, many more of the so-called ‘healthy’ convicts were sent up river to Parramatta only to die and be buried there within a few days, weeks, or months after arriving.[61] While some of those deaths would have resulted from an accident whilst labouring in the colony, just as many, if not more, would have been due to these convicts finally succumbing to the debilitating effects of diseases and malnutrition experienced during transportation. In fact, relapse was all too common in scorbutic people. As Lind noted, in adult cases,

though the recovery of [scorbutic] persons seems promising and speedy at first, yet it requires a much longer continuance of the vegetable diet, and a proper regimen, to perfect it, than is commonly imagined. There are many instances of seamen who have been sent from the hospitals, after having been three weeks or a month on shore, to their respective ships, who in all appearance were in perfect health; yet, in a short time after being on board, relapsed and became highly scorbutic. …

It is indeed frequently experienced, that people once deeply infected, are extremely apt to relapse into symptoms of this disease in different periods of their life afterwards.[62]

Image: James Lind, Stipple engraving by J. Wright after Sir G. Chalmers, (1783), from R. Burgess, Portraits of Doctors & Scientists in the Wellcome Institute, (London 1973), no. 1775.1. Wellcome Library no. 5826i, (CC BY 4.0), Wellcome Collection, Wellcome Library.

Lind’s assertions were wholly corroborated by Governor Sir George Gipps, who noted in a despatch to Lord Glenelg in March 1839 that upon the discharge of a large number of convict scurvy patients from the Lord Lynedoch (1838), ‘many…will however feel the effects of the disease for the rest of their lives.’[63] Only a continued diet of vitamin-C-rich food over the subsequent months could have sustained the health of a four-year-old child who had been dealt such a major blow to her nutrition at a pivotal time in her development. What is the likelihood Mary Grimshaw had access to the optimal diet she needed as a recovering scurvy patient in the colony? The sad fact is, despite being on land, Mary was now in a very young colony where, as a newly arrived convict’s child, she was socially and economically disadvantaged and, as such, would have continued to have a poor, limited diet. The dreaded scurvy was free to rear its ugly head again, and wreak havoc on her tiny body. Scorbutic relapse therefore certainly accounts for the ten-month delay between her sea voyage and her death, whereas the significant gap between Grimshaw’s punishment of Mary and her death had never seemed reasonable to anyone other than D’Arcy Wentworth, who was all but plaiting the rope for Richard Grimshaw’s neck.[64]

So why did Wentworth fail to consider scurvy?

By the time Wentworth came to examine Mary Grimshaw, ten months after she had been at sea, scurvy would not have been suspected. Many in this period thought of scurvy as an exclusively maritime illness, as Lind wrote in 1757: ‘I have been told by some practitioners that this is a disease not met with in people living at land.’[65] Thus blinkered, physicians found the illness only where they expected to find it: on hulks, on ships during lengthy sea voyages, and among passengers disembarking from ships at the end of those journeys, but usually among those who were seafarers by occupation. Yet, the sea itself was not what caused scurvy; it was merely the physical barrier that prevented access to fresh foods containing nutrients that were essential to its prevention. There were, of course, other scenarios in which a nutritious diet was inaccessible to people on dry land, including famine. Lind did, indeed, identify a number of such cases, particularly among poverty-stricken people in Alba (Scotland) who had never undertaken a sea voyage.[66] But Lind was exceptional; for many medical professionals, when scurvy symptoms presented on land, scurvy was not even in the equation; they attributed the symptoms to other illnesses that have common presentations, but not necessarily common treatments, much to the detriment of their patients. Even at sea, where ship surgeons relied heavily on the maritime context to give meaning to the array of symptoms they observed in scorbutic patients, a correct diagnosis of scurvy was notoriously difficult due to its ‘varied disease spectrum,’ that is, the many different ways the deficiency presents in the sufferer, and the fact that it has several stages.[67]As the illness advanced, the symptoms became increasingly horrific and unpredictable. Thus, particularly in the late stages of scurvy, the illness is less obvious because, as Lind noted, ‘It is not easy to conceive a more dismal and diversified scene of misery, than what is beheld in the third and last stage of this calamity; it being then that the anomalous and more extraordinary symptoms most commonly occur.’[68]

Mary’s reported symptoms align with some of those recorded for advanced stage scurvy by Lind and other practitioners. In outlining the disease profile, Lind noted that ‘whatever former ailment the patient has had,’ including ‘aches from bruises, hurts, wounds &c.,’ upon being afflicted with [scorbutus],’ the ‘former and old complaints are renewed, and [the] present malady…rendered worse.’[69] ‘Most, although not all, even in this stage, have a good appetite, and their senses entire, though much dejected, and often low-spirited,’[70] and also have an aversion to using their legs, being moved or touched, since these things cause ‘agony.’[71] These symptoms would account for the ‘rather weakly’ state Greensmith observed in Mary, and could easily have caused her to be irritable or uncooperative, thus instigating the punishment from her father.[72] By stark contrast, Lind noted in his treatise, ‘many’ of these scurvy sufferers ‘make no complaint…when lying at rest in their beds, unless afflicted with the dysentery, or a troublesome salivation,’ which is practically verbatim what Wentworth observed in Mary, who whilst at death’s door in her bed, ‘made no complaint whatever.’[73] Another potential scurvy symptom is the ‘morbid swelling’ Mary exhibited.[74] Vitamin C deficiency causes leaky blood vessels, and the latter leads to haemorrhaging.[75] These haemorrhages are responsible for the characteristic bruise-like ‘scurvy spots,’ (petechiae and ecchymoses), but also typically take the form of subperiosteal haemorrhages and haematomas that occur most frequently in the ‘long bones,’ which is why Scottish cases on land were known as ‘black legs’ rather than scurvy.[76] However, while rare, intraocular and subdural haematomas are also documented features of active scurvy, particularly in paediatric cases.[77] Mary’s ‘violent fever’ was one of the rarer symptoms of end-stage scurvy, as described by Lind, who noted: ‘Some few at this period (though very rarely) fall into colliquative putrid fevers’ and that in those instances ‘fevers of any sort’ always ‘prove fatal.’[78] On the whole, though, the more instantly identifiable features of scurvy, namely the scurvy spots and putrid gums, were not apparent or at least not recognised by Wentworth. However, this could be because Mary was already in the end stages, when ‘the anomalous and more extraordinary symptoms most commonly occur,’ or that, as a paediatric case, the deficiency did not present or progress in a typical way—not even Lind had attempted to cover infantile scurvy in his otherwise ‘exhaustive and masterly’ treatise.[79]

To this day, doctors describe scurvy as an ‘eternal masquerader,’ because all too often it continues to elude formal diagnoses.[80] According to present-day medical researchers, the deficiency is widely thought to be a thing of the past and, specifically, ‘the age of sail,’ so it is still mistaken for everything from osteomyelitis and septic arthritis to haematological and soft tissue malignancies including acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, autoimmune diseases, paediatric syphilis, and the list goes on.[81] Young children with undiagnosed scurvy have therefore been known to suffer through unnecessary treatments including invasive operations with lengthy healing times, when a few weeks’ worth of vitamin C supplements would suffice.[82] And, while scurvy-related haemorrhages typically occur in the ‘long bones, particularly in the metaphyseal region of lower limbs,’ ‘intraocular and subdural haematomas’—like the one D’Arcy Wentworth discovered in Mary—are now ‘a documented feature of active scurvy,’ resulting from the leaky blood vessels associated with the vitamin deficiency rather than from any ‘merciless’ ‘violent blows.’[83] Child abuse remains on scurvy’s long list of differential diagnoses, and holds a special kind of horror among all the misdiagnoses for the nutritional deficiency since it can—and has—led to innocent caregivers being accused of grievous bodily harm and their children being removed from their care.[84] Indeed, it is only in recent times that Australian courts have demonstrated a greater awareness that what might appear to be child abuse by a primary caregiver may actually be caused by a nutritional deficiency that is itself not always the result of general neglect.[85] In the extremely ‘cold case’ of the mysterious death of Mary Grimshaw over two centuries ago, we may have an early example of this very horror story, in which a little girl died in mysterious circumstances months after her arrival in the colony and scurvy was not a suspect in her demise, but child abuse was. The only consolation in the sad tale is that in an era when people were hanged for much less, Mary’s convict father was given the benefit of the doubt and his life was spared.[86]

In the Grimshaw case, the reality is that Mary’s true killer, be it an abusive father, scurvy, or some other unsuspected malady, will forever masquerade as an innocent, simply because it is impossible to identify her killer, beyond all doubt, from a distance of two hundred and seventeen years, especially with such limited evidence. But in opening up and following a new line of enquiry that shines a light on a new suspect, the patient and ‘deceitful’ killer scorbutus, we have come as close as we may ever get to identifying Mary’s destroyer and exonerating her father.[87] In the event that Richard Grimshaw was indeed innocent, it is unlikely he ever understood why he did not have his little girl anymore, but her death at the very least told him that she had been ill and he had to live with the fact that in the last months of her life he had physically punished her for misbehaving when her suffering—whatever its cause—had probably made her irritable and uncooperative. That negative interaction would have been forever seared into his memory as something that was deeply associated with her death. Nor is it hard to imagine that, in their grief and the absence of clear answers, the Grimshaws privately held on to a belief that the punishment Richard gave their daughter must have somehow contributed to Mary’s premature death. One thing is clear: the town did not hold it against Richard Grimshaw. He went on to become a convict constable of Parramatta and in that capacity was regularly entrusted with transporting prisoners as well as with accommodating a man named Joseph Sutton, who ‘was a material evidence for the Crown’ in a major court case; and when Sutton was murdered near James Larra’s Freemason’s Arms on George Street, Parramatta, Richard, the formerly accused murderer, even gave testimony in the subsequent high profile murder trial at the Court of Criminal Jurisdiction.[88] Yet, on the eighteenth anniversary of Mary’s burial, Richard Grimshaw was buried ‘A Lunatic.’[89] While we cannot know what caused his mental illness, one cannot help but wonder if the weight of the shocking allegation and his own lingering doubt might have haunted him to the end, after all.

If this essay has raised any personal issues for you please contact: Lifeline 13 11 14 for Australian residents, or a mental health service near you.

CITE THIS

Michaela Ann Cameron, “The Grimshaws: The Eternal Masquerader,” St. John’s Online, (2021), https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/the-grimshaws, accessed [insert current date].

References

Primary Sources and Databases

- F. M. Bladen (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. IV.—Hunter and King, 1800, 1801, 1802, (Sydney: Charles Potter, Government Printer, 1896).

- Gilbert Blane, “Statements of the Comparative Health of the British Navy, from the year 1779 to the year 1814, with proposals for its farther improvement,” Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, Vol. 6, (1815): 490–573.

- British Newspaper Archive (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/)

- Home Office: Convict Prison Hulks: Registers and Letter Books, 1802–1849, Class: HO9; 5 rolls, (The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England).

- James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757).

- John Marshall, Royal Naval Biography; or Memoirs of the Services of All the Flag-officers, Superannuated Rear-admirals, Retired-captains, Post-captains, and Commanders, Whose Names Appeared on the Admiralty List of Sea Officers at the Commencement of the Present Year, Or who Have Since Been Promoted; Illustrated by a Series of Historical and Explanatory Notes … With Copious Addenda, (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1827).

- Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,”in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812).

- Frederick Watson, Watson & Peter Chapman (eds.), Historical Records of Australia: Series I. Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. XX, February 1839–September 1840, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1924).

- Yorkshire Parish Records, (Leeds, England: West Yorkshire Archive Service).

- Parish Burial Registers, Textual Records, St. John’s Anglican Church, Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia.

- Trove (https://trove.nla.gov.au/)

Secondary Sources including Medical Literature

- Anil Agarwal, Abbas Shaharyar, Anubrat Kumar, Mohd Shafi Bhat, Madhusudan Mishra, “Scurvy in pediatric age group – A disease often forgotten?” Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma, Vol. 6, No. 2 (June, 2015): 101–7.

- B. Barrett Gilman and Radford C. Tanzer, “Subdural Hematoma in Infantile Scurvy: Report of Case with Review of Literature,” JAMA, Vol. 99, No. 12 (1932): 989–991.

- Sarah Benezech, Chrystele Hartmann, Diane Morfin, Yves Bertrand, Carine Domenech, “Is it leukemia, doctor? No, it’s scurvy induced by an ARFID!” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 74, No. 8 (Aug, 2020): 1247–1249.

- Wajdi Bouaziz, Mohamed Ali Rebai, Mohamed Ali Rekik, Nabil Krid, Zoubaier Ellouz, Hassib Keskes, “Scurvy: When it is a Forgotten Illness the Surgery Makes the Diagnosis,” The Open Orthopaedics Journal, No. 11 (2017): 1314–1320.

- Alice Brambilla, Cristina Pizza, Donatella Lasagni, Lucia Lachina, Massimo Resti and Sandra Trapani, “Pediatric Scurvy: When Contemporary Eating Habits Bring Back the Past,” Frontiers in Pediatrics, Vol. 6, Article 126,(May 2018).

- Karen L. Christopher, Kelly K. Menachof and Ramin Fathi, “Scurvy masquerading as reactive arthritis,” Cutis, Vol. 103, No. 3 (March, 2019): E21–E23.

- Owen Dyer, “Brain haemorrhage in babies may not indicate violent abuse,” BMJ, Vol. 326, (March, 2003): 616.

- Mark A. Francescone and Jacob Levitt, “Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature,” Cutis, Vol. 76 No. 4 (Oct., 2005): 261–6.

- Eva Lai-Wah Fung and Edmund Anthony Severn Nelson, “Could Vitamin C deficiency have a role in shaken baby syndrome?” Paediatrics International, Vol. 46, (2004): 753–755.

- P. Gupta, K. Taneja, P. U. Iyer, M. V. Murali and S. M. Tuli, “Scurvy: the eternal masquerader,” Annals of Tropical Paediatrics, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1989): 118–121.

- Michael D. Innis, “Autoimmune Tissue Scurvy Misdiagnosed as Child Abuse,” Clinical Medicine Research, Vol. 2, No. 6, (Nov., 2013): 154–157.

- Nadir Khan, J. M. Furlong-Dillard, and Robert F. Buchman, “Scurvy in an autistic child: early disease on MRI and bone scintigraphy can mimic an infiltrative process,” BJR Case Reports, Vol. 1, No. 3 (2015): 20150148.

- Laura M. Kinlin, Ana C. Blanchard, Shawna Silver, Shaun K. Morris, “Scurvy as a mimicker of osteomyelitis in a child with autism spectrum disorder,” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 69, (April, 2018): 99–102.

- Emily J. Liebling, Raymond W. Sze & Edward M. Behrens, “Vitamin C deficiency mimicking inflammatory bone disease of the hand,” Pediatric Rheumatology, Vol. 18, No. 45 (2020).

- S. Mays, “A Likely Case of Scurvy from Early Bronze Age Britain,” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Vol. 18, (2018): 178–187.

- Takuma Miura, Hisao Tanaka, Michio Yoshinari, Akiko Tokunaga, Shinobu Koto, Kazuo Saito, Jiro Izumi, Minoru Inagaki, “A Case of Scurvy with Subdural Hematoma,” Rinsho Ketsueki, Vol. 23, No. 8, (1982): 1235–1250.

- Paul Mogle and Joe Zias, “Trephination as a possible treatment for scurvy in a middle bronze age (ca. 2200 BC) skeleton,” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Vol. 5, No. 1, (March, 1995): 77–81.

- Husna Musa, Imma Isniza Ismail and Nurul Hazwani Abdul Rashid, “Paediatric scurvy: frequently misdiagnosed,” Paediatrics and International Child Health, (Sep., 2020): 1–4.

- S. Ramar, V. Sivaramakrishnan and K. Manoharan, “Scurvy: a forgotten disease,” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Vol. 74, No. 1 (1993): 92–95.

- Anne Marie E. Snoddy, Hallie R. Buckley, Gail E. Elliott, Vivien G. Standen, Bernardo T. Arriaza, Siân E. Halcrow S, “Macroscopic features of scurvy in human skeletal remains: A literature synthesis and diagnostic guide,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 167, No. 4 (2018): 876–895.

- G. F. Still, “Infantile Scurvy: Its History,” Archives of Disease in Childhood, (Aug, 1935): 211–218.

- Rehan Ul Haq, Ish Kumar Dhammi, Anil K. Jain, Puneet Mishra, K. Kalivanan, “Infantile scurvy masquerading as bone tumour,” Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, Vol. 42, No. 7 (July, 2013): 363–5.

NOTES

[1] “On Saturday the 7th Instant and Inquest…,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 15 January 1804, p. 2.

[2] “RICHARD GRIMSHAW per Glatton (1803),” New South Wales Government, Bound Manuscript Indents, 1788–1842, Series: NRS 12188; Item: [4/4004]; Microfiche: 631, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia); “RICHARD GRIMSHAW per Glatton (1803),” Home Office: Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, Class: HO 10; Piece: 3, (The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England).

[3] “Baptism of RICHARD GRIMSHAW, 12 May 1768; Baptism Place: Birstall, St. Peter, Yorkshire, England; Father: Abraham Grimshaw of Heckmondwike,” Yorkshire Parish Records, (Leeds, England: West Yorkshire Archive Service). “Marriage of ABRAHAM GRIMSHAW and DOROTHY PRESTON, 27 January 1761; Marriage Place: Birstall, St. Peter, Yorkshire, England,” Yorkshire Parish Records, (Leeds, England: West Yorkshire Archive Service). “Marriage of RICHARD GRIMSHAW and MARY LANGFIELD, 1 December 1788; Marriage Place: Ackworth, York, England,” England, Marriages, 1538–1973, (Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013).

[4] “Baptism of JOHN GRIMSHAW; Born: 2 June 1789; Baptised: 12 June 1789; Baptism Place: Ackworth, St. Cuthbert, Yorkshire, England; Father: RICHARD GRIMSHAW; Mother: MARY GRIMSHAW”; “Baptism of WILLIAM GRIMSHAW; Born: 13 June 1791; baptised: 7 August 1791; Baptism Place: Ackworth, St. Cuthbert, Yorkshire, England; Father: RICHARD GRIMSHAW; Mother: MARY GRIMSHAW”; “Baptism of THOMAS GRIMSHAW; Born: 18 May 1795; Baptised: 14 June 1795; Baptism Place: Ackworth, St. Cuthbert, Yorkshire, England; Father: RICHARD GRIMSHAW, Labourer of Lowtown; Mother: MARY GRIMSHAW”; “Baptism of MARY GRIMSHAW; Born: 7 June 1798; Baptised: 15 June 1798; Baptism Place: Ackworth, St. Cuthbert, Yorkshire, England; Father: RICHARD GRIMSHAW, Labourer of Lowtown; Mother: MARY GRIMSHAW”; “Baptism of ELIZABETH GRIMSHAW; Born: 17 January 1801; Baptised: 9 August 1801; Baptism Place: Ackworth, St. Cuthbert, Yorkshire, England; Father: RICHARD GRIMSHAW; Mother: MARY GRIMSHAW”; New Reference Number: WDP77/4, Yorkshire Parish Records, (Wakefield, Yorkshire, England: West Yorkshire Archive Service).

[5] See the “Duty” column in “Baptism of JOHN GRIMSHAW; Born: 2 June 1789; Baptised: 12 June 1789; Baptism Place: Ackworth, St. Cuthbert, Yorkshire, England; Father: RICHARD GRIMSHAW; Mother: MARY GRIMSHAW”; “Baptism of WILLIAM GRIMSHAW; Born: 13 June 1791; baptised: 7 August 1791; Baptism Place: Ackworth, St. Cuthbert, Yorkshire, England; Father: RICHARD GRIMSHAW; Mother: MARY GRIMSHAW,” New Reference Number: WDP77/4, Yorkshire Parish Records, (Wakefield, Yorkshire, England: West Yorkshire Archive Service).

[6] “Baptism of ELIZABETH GRIMSHAW; Born: 17 January 1801; Baptised: 9 August 1801; Baptism Place: Ackworth, St. Cuthbert, Yorkshire, England; Father: RICHARD GRIMSHAW, Labourer; Mother: MARY GRIMSHAW; Place of Abode: Moor Top”; New Reference Number: WDP77/4, Yorkshire Parish Records, (Wakefield, Yorkshire, England: West Yorkshire Archive Service). For mention of Richard being a private in the 3rd Regiment of Food Guards see “York, &c News,” York Herald, Yorkshire, England, Saturday 18 July 1801, pp. 2–3.

[7] “York, &c News,” York Herald, Yorkshire, England, Saturday 18 July 1801, pp. 2–3.

[8] “York Assizes,” The Morning Post, London, London, England, Monday 3 August 1801, p. 3.

[9] “York Assizes,” The Morning Post, London, London, England, Monday 3 August 1801, p. 3.

[10] “RICHARD GRIMSHAW; Hulk: Captivity; Place Moored: Portsmouth,” Home Office: Convict Prison Hulks: Registers and Letter Books, 1802–1849, Class: HO9; 5 rolls, (The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England).

[11] Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,” in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812), p. 620.

[12] Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,” in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812).

[13] Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,” in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812), p. 620.

[14] Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,” in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812), pp. 620–1.

[15] Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,” in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812), p. 621.

[16] Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,” in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812), p. 621.

[17] These ‘sore legs’ were probably early signs of these men being afflicted with scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency). Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,” in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812), p. 621.

[18] “York Assizes,” The Morning Post, London, London, England, Monday 3 August 1801, p. 3.

[19] “York Assizes,” The Morning Post, London, London, England, Monday 3 August 1801, p. 3.

[20] Thomas Pelham, “Lord Pelham to The Treasury, Whitehall, 12 May 1802,” in F. M. Bladen (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. IV.—Hunter and King, 1800, 1801, 1802, (Sydney: Charles Potter, Government Printer, 1896), p. 752; “Ship News,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 19 March 1803, p. 3.

[21] “Ship News,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 19 March 1803, p. 3; Gilbert Blane, “Statements of the Comparative Health of the British Navy, from the year 1779 to the year 1814, with proposals for its farther improvement,” Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, Vol. 6, (1815): 567.

[22] John Marshall, Royal Naval Biography; or Memoirs of the Services of All the Flag-officers, Superannuated Rear-admirals, Retired-captains, Post-captains, and Commanders, Whose Names Appeared on the Admiralty List of Sea Officers at the Commencement of the Present Year, Or who Have Since Been Promoted; Illustrated by a Series of Historical and Explanatory Notes … With Copious Addenda, (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1827), p. 109 citing Gilbert Blane, “Statements of the Comparative Health of the British Navy, from the year 1779 to the year 1814, with proposals for its farther improvement,” Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, Vol. 6, (1815): 566–7.

[23] “Ship News,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 19 March 1803, p. 3.

[24] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 104.

[25] Henry St. John Mildmay and James Neild, “No. 1. Report on the State of the Convicts in Portsmouth Harbour, March 16, 1802,” in James Neild, State of the Prisons in England, Scotland and Wales, extending to various places therein assigned, not for the debtor only, but for felons also, and other less criminal offenders, together with some useful documents, observations, and remarks, adapted to explain and improve the condition of prisoners in general, (London: John Nichols and son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812), p. 621.

[26] “Ship News,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 19 March 1803, p. 3.

[27] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), pp. 136–7, 194–6.

[28] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), pp. 137–8.

[29] “Ship News,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 19 March 1803, p. 3.

[30] For reference to the living arrangements and their timeframe, see “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[31] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[32] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[33] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[34] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[35] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[36] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[37] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[38] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[39] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[40] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2; “On Saturday the 7th Instant and Inquest…,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 15 January 1804, p. 2; “Burial of MARY GRIMSHAW, 5 January 1804, Abode: Parramatta; Age: not recorded; By whom the burial was registered: Samuel Marsden; Remarks: Child,” Parish Burial Registers, Textual Records, St. John’s Anglican Church, Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia.

[41] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[42] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[43] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[44] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[45] “On Saturday the 7th Instant and Inquest…,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 15 January 1804, p. 2.

[46] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[47] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[48] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[49] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[50] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[51] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[52] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[53] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[54] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[55] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[56] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[57] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[58] “Ship News,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 19 March 1803, p. 3.

[59] “Ship News,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 19 March 1803, p. 3.

[60] “Ship News,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 19 March 1803, p. 3.

[61] For a discussion making specific mention of supposedly ‘healthy’ people being sent up river to Parramatta to work, only to die within days, weeks or months, see Michaela Ann Cameron, “The Taylors: ‘I Am But Sleeping Here,’” St. John’s Online, (2020), https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/the-taylors/, accessed 17 March 2021. See, generally, too, the Parish Burial Register, Textual Records, St. John’s Anglican Church, Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia.

[62] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), pp. 196–7.

[63] George Gipps, “Sir George Gipps to Lord Glenelg, Government House, 8 March 1839,” in Frederick Watson, Watson & Peter Chapman (eds.), Historical Records of Australia: Series I. Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. XX, February 1839–September 1840, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1924), p. 57.

[64] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[65] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 121.

[66] See “Letter from Dr. James Grainger, physician in London, late surgeon to Lt-Gen. Pulteney’s regiment,” and “Extract of a letter received from Dr. Huxham, physician in Plymouth,” in James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), pp. 127 and 131 respectively.

[67] James Lind described scurvy as “a disease attended with so many and various symptoms” including “most common and constant symptoms,…casual and accidental [symptoms]…And…Some extraordinary and uncommon symptoms, that sometimes, though seldom, have happened in it; and which occur only in the highest and most virulent state of this disease, from the peculiar idiosyncrasy of the patient, its combination with other malignant diseases, or from other incidental circumstances.” Lind also included in his treatise letters from colleagues containing “accounts of the unlucky and sometimes fatal errors they ha[d] fallen into by mistaking this disease.” See James Lind, James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), pp. 103, 124, 128.

[68] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 119.

[69] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 112.

[70] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 119. Eva Lai-Wah Fung and Edmund Anthony Severn Nelson also describe scurvy’s typical presentation of ‘non-specific symptoms of listlessness, loss of appetite, irritability and failure to thrive. Affected children could have tender extremities, which may or may not be swollen as a result of subperiosteal hemorrhages. In advanced cases, a scorbutic rosary is present. Purpura or petechiae may be observed over the skin. Gum swelling may not be obvious initially and a more general bleeding diathesis has also been reported.” See Eva Lai-Wah Fung and Edmund Anthony Severn Nelson, “Could Vitamin C deficiency have a role in shaken baby syndrome?” Pediatrics International, Vol. 46, (2004): 753–755, esp. 753.

[71] See “Letter from Dr. James Grainger, physician in London, late surgeon to Lt-Gen. Pulteney’s regiment,” and “Extract of a letter received from Dr. Huxham, physician in Plymouth,” in James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 125 and Lind himself, who writes “And as scorbutic pains in general are very liable to move from one place to another, so that are always exasperated by motion of any sort, especially the pain of the back; which, upon this occasion, proves very troublesome,” on pp. 109–10. For a more recent medical study mentioning mobility problems relating to infantile scurvy see Nadir Khan, J. M. Furlong-Dillard, and Robert F. Buchman, “Scurvy in an autistic child: early disease on MRI and bone scintigraphy can mimic an infiltrative process,” BJR Case Reports, Vol. 1, No. 3 (2015): 20150148. Lind asserts that ‘whatever former ailment the patient has had,’ including ‘aches from bruises, hurts, wounds &c.,’ upon being afflicted with [scorbutus],’ the ‘former and old complaints are renewed, and [the] present malady…rendered worse,’

[72] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[73] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 118; “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[74] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[75] B. Barrett Gilman and Radford C. Tanzer, “Subdural Hematoma in Infantile Scurvy: Report of Case with Review of Literature,” JAMA, Vol. 99, No. 12 (1932): 989–991; S. Mays, “A Likely Case of Scurvy from Early Bronze Age Britain,” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Vol. 18, (2018): 178–187 https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.930; James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 117.

[76] See “Letter from Dr. James Grainger, physician in London, late surgeon to Lt-Gen. Pulteney’s regiment,” and “Extract of a letter received from Dr. Huxham, physician in Plymouth,” in James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), pp. 121, 127. Nadir Khan, J. M. Furlong-Dillard, and Robert F. Buchman, “Scurvy in an autistic child: early disease on MRI and bone scintigraphy can mimic an infiltrative process,” BJR Case Reports, Vol. 1, No. 3 (2015): 20150148; Takuma Miura, Hisao Tanaka, Michio Yoshinari, Akiko Tokunaga, Shinobu Koto, Kazuo Saito, Jiro Izumi, Minoru Inagaki, “A Case of Scurvy with Subdural Hematoma,” Rinsho Ketsueki, Vol. 23, No. 8, (1982): 1235–1250.

[77] See Takuma Miura, Hisao Tanaka, Michio Yoshinari, Akiko Tokunaga, Shinobu Koto, Kazuo Saito, Jiro Izumi, Minoru Inagaki, “A Case of Scurvy with Subdural Hematoma,” Rinsho Ketsueki, Vol. 23, No. 8, (1982): 1235–1250. Miura et. al write: “It is said that scurvy is now an uncommon disease in the pediatric field. Only a few papers on this disease were reported in these five years. In our hospital a 5-month-old female baby was admitted with bleeding tendencies such as purpura, vomiting and bulging of the anterior fontanelle. On admission coagulation studies including bleeding time, PT, APTT, platelet aggregation (ADP; collagen, epinephrine and ristocetin) and so on, revealed no abnormal findings except positive Rumpel-Leede test. Roentgenograms of the lower extremities showed subperiosteal hemorrhage, thinning of cortex and a scurvy line. Subdural hematoma was found in CT-scanning and she was diagnosed as scurvy with subdural hematoma. We performed an operation of a subdural-peritoneal shunt and prescribed vitamin C. The prognosis was good. Since it was found that the formula milk for this baby had been prepared with boiling water, the level of vitamin C was assayed. The result revealed that the level of vitamin C in the formula with boiling water was decreased to 42.6% of the original source.” Similarly, “In 1778,” writes G. F. Still, “De Mertans, in a paper communicated to the Royal Society, describing the terrible incidence of scurvy amongst the children in a Foundling institution in St. Petersburg, recognized not only the antiscorbutic value of vegetables, but its diminution after cooking. ‘I am convinced,’ he says, ‘that all the greens used in our kitchens are much more antiscorbutic when they are raw than after they have been boiled in water or have through any other preparation by fire.” G. F. Still, “Infantile Scurvy: Its History,” Archives of Disease in Childhood, (Aug, 1935): 214; Paul Mogle and Joe Zias, “Trephination as a possible treatment for scurvy in a middle bronze age (ca. 2200 BC) skeleton,” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Vol. 5, No. 1, (March, 1995): 77–81 is a particularly interesting study, considering that Wentworth, who did not even suspect scurvy, had considered using the same treatment of trepanation / trephination on Mary Grimshaw’s ‘morbid swelling’ at the back of her neck extending to her left ear.

[78] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 112.

[79] James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 119; G. F. Still, “Infantile Scurvy: Its History,” Archives of Disease in Childhood, (Aug, 1935): 214.

[80] P. Gupta, K. Taneja, P. U. Iyer, M. V. Murali and S. M. Tuli, “Scurvy: the eternal masquerader,” Annals of Tropical Paediatrics, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1989): 118–121 doi: 10.1080/02724936.1989.11748611. James Grainger wrote: “I have been favoured with several letters by different gentlemen, giving an account of the unlucky and sometimes fatal errors they have fallen into by mistaking this disease.” For the Grainger letter see James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 128.

[81] S. Ramar, V. Sivaramakrishnan and K. Manoharan, “Scurvy: a forgotten disease,” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Vol. 74, No. 1 (1993): 92–95; Laura M. Kinlin, Ana C. Blanchard, Shawna Silver, Shaun K. Morris, “Scurvy as a mimicker of osteomyelitis in a child with autism spectrum disorder,” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 69, (April, 2018): 99–102; Emily J. Liebling, Raymond W. Sze & Edward M. Behrens, “Vitamin C deficiency mimicking inflammatory bone disease of the hand,” Pediatric Rheumatology, Vol. 18, Article number 45 (2020). Anil Agarwal, Abbas Shaharyar, Anubrat Kumar, Mohd Shafi Bhat, Madhusudan Mishra, “Scurvy in pediatric age group – A disease often forgotten?” Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma, Vol. 6, No. 2 (June, 2015): 101–7. Sarah Benezech, Chrystele Hartmann, Diane Morfin, Yves Bertrand, Carine Domenech, “Is it leukemia, doctor? No, it’s scurvy induced by an ARFID!” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 74, No. 8 (Aug, 2020): 1247–1249; Karen L. Christopher, Kelly K. Menachof and Ramin Fathi, “Scurvy masquerading as reactive arthritis,” Cutis, Vol. 103, No. 3 (March, 2019): E21–E23; Rehan Ul Haq, Ish Kumar Dhammi, Anil K. Jain, Puneet Mishra, K. Kalivanan, “Infantile scurvy masquerading as bone tumour,” Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, Vol. 42, No. 7 (July, 2013): 363–5; For a case involving scurvy in an adult see Mark A. Francescone and Jacob Levitt, “Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature,” Cutis, Vol. 76 No. 4 (Oct., 2005): 261–6. Husna Musa, Imma Isniza Ismail and Nurul Hazwani Abdul Rashid, “Paediatric scurvy: frequently misdiagnosed,” Paediatrics and International Child Health, (Sep., 2020): 1–4.

[82] In Laura M. Kinlin, Ana C. Blanchard, Shawna Silver, Shaun K. Morris, “Scurvy as a mimicker of osteomyelitis in a child with autism spectrum disorder,” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 69, (April, 2018): 99–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.02.002 “A case of scurvy in a 10-year-old boy with autism spectrum disorder is described. His clinical presentation was initially thought to be due to osteomyelitis, for which empirical antimicrobial therapy was initiated. Further invasive and ultimately unnecessary investigations were avoided when scurvy was considered in the context of a restricted diet and classic signs of vitamin C deficiency. Infectious diseases specialists should be aware of scurvy as an important mimicker of osteoarticular infections when involved in the care of patients at risk of nutritional deficiencies.” For more on the importance of suspecting scurvy to ‘avoid unnecessary invasive diagnostic procedures’ see also Alice Brambilla, Cristina Pizza, Donatella Lasagni, Lucia Lachina, Massimo Resti and Sandra Trapani, “Pediatric Scurvy: When Contemporary Eating Habits Bring Back the Past,” Frontiers in Pediatrics, Vol. 6, Article 126,(May 2018). Wajdi Bouaziz, Mohamed Ali Rebai, Mohamed Ali Rekik, Nabil Krid, Zoubaier Ellouz, Hassib Keskes, “Scurvy: When it is a Forgotten Illness the Surgery Makes the Diagnosis,” The Open Orthopaedics Journal, No. 11 (2017): 1314–1320.

[83] Anne Marie E. Snoddy, Hallie R. Buckley, Gail E. Elliott, Vivien G. Standen, Bernardo T. Arriaza, Siân E. Halcrow S, “Macroscopic features of scurvy in human skeletal remains: A literature synthesis and diagnostic guide,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 167, No. 4 (2018): 876–895. G. F. Still mentions a fatal case of scurvy with subdural haematoma dating to 1862 in G. F. Still, “Infantile Scurvy: Its History,” Archives of Disease in Childhood, (Aug, 1935): 215.

[84] Owen Dyer, “Brain haemorrhage in babies may not indicate violent abuse,” BMJ, Vol. 326, (March, 2003): 616. For an article that advises caution in drawing conclusions about the role of vitamin C deficiency in shaken baby syndrome, however, see Eva Lai-Wah Fung and Edmund Anthony Severn Nelson, “Could Vitamin C deficiency have a role in shaken baby syndrome?” Paediatrics International, Vol. 46, (2004): 753–755.

[85] As Owen Dyer states: “Juries like experts who seem sure of the facts, whereas when I appear I have to say I don’t know what caused the death. I’m certainly not advocating letting baby killers walk free…The cases that worry me are the ones where the medical evidence is the only real evidence. Am I saying such people must be acquitted? Yes I am.” Owen Dyer, “Brain haemorrhage in babies may not indicate violent abuse,” BMJ, Vol. 326, (March, 2003): 616. See in particular the comments of Honorary Consultant Haematologist at Brisbane’s Princess Alexandra Hospital, Michael D. Innis, posted in the “response” section to the Dyer article, as well as an Australian case Innis referred to: “Perth man found not guilty in ‘baby shaking’ case,” ABC News, (3 June 2003), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2003-06-03/perth-man-found-not-guilty-in-baby-shaking-case/1864396?utm_source=abc_news_web&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_content=link&utm_campaign=abc_news_web, accessed 18 March 2021. See also Michael D. Innis, “Autoimmune Tissue Scurvy Misdiagnosed as Child Abuse,” Clinical Medicine Research, Vol. 2, No. 6, (Nov., 2013): 154–157, doi: 10.11648/j.cmr.20130206.17

[86] “Trial of Richard Grimshaw,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 January 1804, p. 2.

[87] James Lind frequently refers to scurvy’s “deceitful” character. See James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in three parts, Containing An Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease, Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, (The Strand, London: A. Miller, 1757).

[88] New South Wales Government, Special Bundles, 1794–1825, Series: NRS 898; Reels: 6020–6040, 6070; Fiche: 3260–3312, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia). See “Trial for the Murder of Joseph Sutton,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 27 March 1813, p. 2.