Supported by a Create NSW Arts and Cultural Grant – Old Parramattans & Murder Tales

WARNING: This essay discusses a violent murder and contains images of post-mortem punishment, which may be distressing for some readers. Members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are further advised that this essay discusses frontier violence. Reader discretion is advised.

‘…And the Dead Shall Rise’

Easter 1809 would be like no other William Hosking had ever experienced in his eight years of life, for this was his first colonial Easter, and he was to spend it with the Hassalls, at their picturesque High Street (George Street) residence in Parramatta, Burramattagal Country.[1] He found Hassall House ‘shrouded in a grove of orange trees and laburnums’ while in the back ‘there was a beautiful avenue of orange and lemon, and lime trees, which finished in a large Cape mulberry arbour. To the right and left were evergreen and deciduous peach trees, mingled with apricot, nectarine, apple, pomegranate, fig, chestnut, English mulberry, and a great variety of other fruit trees…The walls were bordered with rose-trees, geraniums, and a hundred beautiful and odoriferous shrubs, that in’ his native land, England, ‘bloom[ed] but to die.’[2]

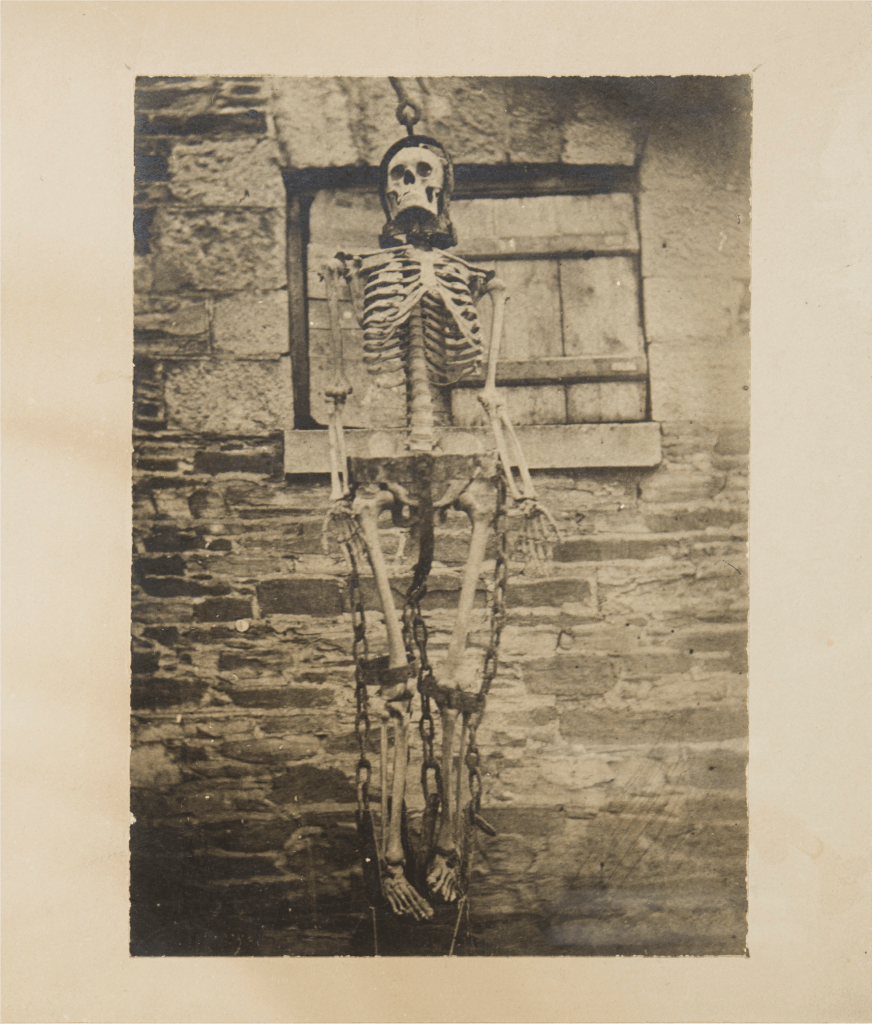

Nevertheless, even amid these polysensory delights, William’s mind was preoccupied with the thoughts of a public execution and the subsequent ‘rising’ of the dead man’s body: yet it was not Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection that he dwelt upon, as he ought to have done at this time of year. The dead man who captivated William was not an ‘exalted’ one, rising body and soul to heaven but, rather, a murderer who was hanged at Cadi (Sydney) and, ‘having remained the usual time suspended,’ had been taken down and sent to Parramatta, where his cadaver was thrown inside a custom-made iron gibbet, and unceremoniously hoisted up again just beyond the Hassall’s rose-bordered walls, on ‘the hill to the south of town’ (present-day Lancer Barracks).[3] There he had dangled only two summers before, silently screaming his homily against the sin of murder at passers-by, his flesh baking and rotting in the searing hot, late January sun for the local wildlife to pluck and devour.

It is actually rather fitting that William Hosking learnt of what befell this Parramatta murderer at Easter time, as the grisly post-mortem punishment to which this criminal corpse had been subjected was preferred because of how it aligned with Christian beliefs regarding what happened to the bodies and souls of believers on Judgement Day. ‘Christ…shall come to judge the quick and the dead. At whose coming all men shall rise again with their bodies: and shall give account for their own works,’ so it says in ‘St. Athanasius’ Creed’ in the Book of Common Prayer (1662).[4] Thus, for centuries, right up until the 1830s, people continued to interpret these words in such a way that they believed one had to be properly buried according to religious rites and, further, that the body had to be intact to be resurrected. Inevitably, this led to criminals of all kinds being sentenced to execution and dissection on the anatomist’s slab or disintegration on a public gibbet so that they were not only condemned to death for their crimes, but went to their deaths knowing they would also be prevented from rising ‘to the life immortal’ for all eternity.[5] During the time of Britain’s ‘Bloody Code,’ however, many crimes were capital offences, with no differentiation between severe and minor cases, and murder was on the rise.[6] To ‘better prevent…the horrid Crime of Murder’ specifically, then, the Murder Act 1751 was established; it added ‘some further Terror and peculiar Mark of Infamy…to the Punishment of Death,’ stating that ‘in no case whatsoever shall the Body of any Murderer be suffered to be buried, unless after such Body shall have been either…dissected or hung in chains, as to the Court shall seem meet…whichsoever of the two the Court shall order.’[7]

In the Colony of New South Wales, out of the two marks of infamy available to them, we find judges typically opted for the sufficiently horrifying punishment of anatomisation and dissection of murderers rather than ‘hanging in chains.’[8] Anatomisation and dissection would have been the more common post-execution punishment for a number of medical reasons. At a time when a fresh criminal cadaver had value for medical education and research yet Christian beliefs discouraged non-criminals from voluntarily donating their remains to medicine, a rotting corpse in a gibbet would have been a wasted, precious resource. The public display of a decaying body in a visible area of town also raised serious public health concerns, not to mention moral, spiritual and psychological ones. Ultimately, it was seen as ‘a practice which wounds only the living,’ insofar as it unfairly inflicted this pestilential punishment on an ‘innocent neighbourhood.’[9] Therefore, in the colony, as elsewhere among Britain’s subjects, ‘there were often particular aggravations’ that saw only a minority of offenders gibbetted.[10]

So who was this man with the ‘brand of Cain’? Who was his victim? And what was it about this murderer’s crime that singled him out for a punishment that was apparently reserved for the most atrocious?

The Man in the Gibbet

“No, no; let them hang, and their names rot,

and their crimes live for ever against them”

—The Pilgrim’s Progress[11]

While the man in the gibbet did indeed hang, not only at his execution in Cadi (Sydney) but also ‘in chains’ at Parramatta, curiously, the stench of his befouled name has not lingered, nor has his crime lived forever against him. For a criminal punishment invented for the purpose of prolonging the horror and infamy of public execution, it is ironic that the name and crime of this man in the gibbet has failed to endure in our collective psyche. Surely, his was a name that would have been passed down via oral tradition over the two centuries since his crime, and been as familiar to us as other legendary Australian rogues: the budding dark tourist William Hosking’s fascination for this particular tale, as well as the macabre details the locals had evidently eagerly shared with him, gave early indications that it would be preserved in local legend at the very least. For here was a man whose crime of murder had been considered so heinous that he was made the, emphatically, rare subject of this ‘revolting and disgraceful spectacle’ in the early Colony of New South Wales.[12]

As expected, others within the very exclusive club of his fellow gibbetted ones in the penal colony have retained a comparatively prominent position in our nation’s hall of infamy. For example, many know that in November 1796 the convict Francis Morgan was hanged for murder and gibbetted on the rocky outcrop Mattewanye (Fort Denison) or ‘Pinchgut,’ as the isle of punishment was nicknamed by settlers, and that his body remained there, hanging in chains, for years.[13] At Parramatta in Burramattagal Country, the convict and Irish rebel Samuel Humes was also hanged and gibbetted for his role as a ringleader of the ‘Castle Hill Convict Rebellion’ in 1804.[14] But our murderer, despite being publicly displayed in the gibbet irons on the hill to the south of town, has somehow, in the passage of time, achieved a level of anonymity that clearly none of his contemporaries felt he deserved.[15] Hosking’s anonymous and highly censored account of his time at Parramatta and the murder case that so enthralled him is only partially to blame for this, because even when all of those mysteries are adequately solved, the identity of the man in the gibbet continues to elude and taunt the modern researcher. For at the end of all those investigations, we do at last know his rotten name—John Kenny—but we are confronted with a new mystery: which John Kenny was he?

There were two contenders in this period: John Kenny per Boddingtons (1793) and John Kenny per Britannia (1797). And, despite the fact both John Kennys were thieving Irish convicts, to date, researchers have been unwilling to argue that the John Kenny who, along with his convict brother James Kenny, briefly occupied a position of trust and respectability as the first Catholic school teacher in Australia, might have ended his days strung up on a gibbet in Parramatta. The fact is that such paradoxical types were exactly the sorts that abounded in the penal colony: convict constables, gentleman rogues, and eventually even a convict mayor, to name but a few. Here, it was entirely within the realms of possibility that an Irishman the governor had entrusted to lift up ‘the rising generation’ of his fellow Irish convicts’ children as their teacher could himself become a grisly lesson in the consequences of committing murder. But whilst possible, is it what actually happened? In the interests of leaving no stone unturned, let us do what others have been seemingly disinclined to do thus far: let us stare unflinchingly at the available evidence to explore the theory that John Kenny, Australia’s first Catholic school teacher, and John Kenny, the gibbetted murderer, were one in the same.

The Kenny Brothers

John and James Kenny were in their early twenties when they were tried and convicted at Contae Cheatharlach (County Carlow), Éire (Ireland), for the crime of robbery and sentenced to seven years transportation in August 1791. John was the elder of the two by about a year, based on ages recorded in their convict indents, but these early indents unfortunately tell us little else. The brothers sailed from Contae Chorcaí (County Cork) on 15 February 1793 per Boddingtons (1793) and arrived at Warrane (Sydney Cove) on 7 August the same year. Ann Kenny, ‘the daughter of John and Mary Kenny,’ was born on 20 March 1795 and baptised in the parish of St. Philip’s, Cadi (Sydney), on 26 May.[16]

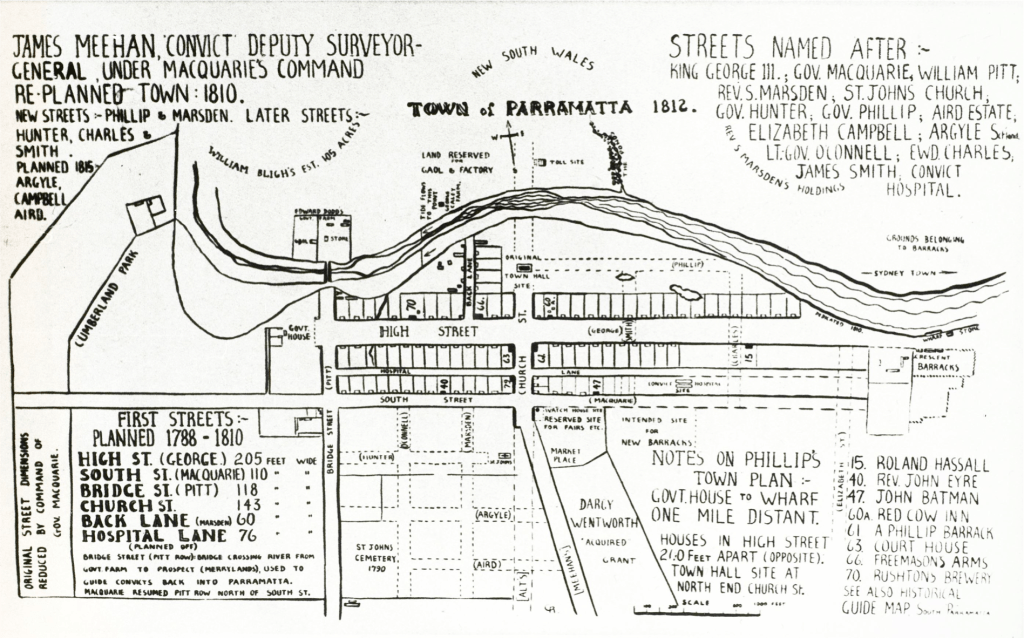

The Kenny brothers must have conducted themselves well, because on 30 December 1796, less than four years after arriving as convicts, they both received land grants next to each other in the Field of Mars, north of Parramatta, in Wallumettagal Country. Within a few months of receiving the grant, John and his wife welcomed a son, ‘Morris Kenny.’[17] At sixty acres, John’s grant was twice the size of James’s. Farming was not for everyone, and in the Field of Mars especially in this period, there were few who stuck to it for the long haul, so grants frequently changed hands. For example, on 20 March 1799, James finally set himself apart from his elder brother by selling his thirty acres to John Warby, who sold it at a loss the very next day to John Macarthur, and the following month, the grant belonging to the Kenny brothers’ neighbour, Simon Taylor, would also change hands after Taylor was executed for murdering his wife, Anne.[18] In the absence of any evidence to suggest otherwise, it seems John Kenny held on to his Field of Mars grant or at least remained in the Parramatta district, because on 22 April 1799, his two-year-old son Morris was finally baptised at St. John’s, Parramatta.[19] If nothing else, then, the Kenny Farms somewhere to the north of the town of Parramatta in present-day Carlingford and the Hills district connect John Kenny the future schoolteacher to Parramatta and surrounds, whereas there is no evidence tying the other John Kenny to the region at any time.[20]

While the Kennys’ convict indents were sparse, their colonial circumstances reveal that they were Roman Catholic and educated.[21] Once they were emancipated and established in their new community, irrespective of what their occupations had been at home in Éire (Ireland), their religion, literacy, and numeracy were aspects of their identities that took on great if not entirely new significance in the colonial context; something which could not have happened at all if not for the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, which was passed the same year the Kennys committed their crime.[22] The Act allowed Catholics to practice law, exercise their religion, and teach in their own schools, and for the children of Irish Catholic convicts in the colony it was passed not a moment too soon.[23] After all, using the Parramatta murders as a small dataset, we find Irish convicts and emancipists making up the majority of victims, and that the murderers more often than not were Irish, too. Excessive alcohol consumption was also frequently cited as an aggravating factor in many of those violent crimes. In this context, the authorities increasingly saw that providing an education to convicts’ innocent, colonial-born children (Irish and otherwise) was a means of breaking the cycle of illiteracy, unskilled labour, loose morals, criminality, and alcohol abuse, all of which had seen their convict parents transported in the first place, continued to place them in dangerous—if not fatal—situations, and compromised the overall public morality of the penal colony. In spite of Protestant and Catholic tensions, which reached a fever pitch in 1804 during the Convict Rebellion at Mogoaillee (Castle Hill) in Bidjigal Country led by Irish convicts and their sympathisers, therefore, the very next year Governor King was only too glad to permit the Kennys to open the first school for Irish Catholic children at Cadi (Sydney) and to support it with government money:

…there are three [schools] at Sydney (one of which is for Catholic children), two at Parramatta, one at Toongabbe [sic], and one at Kissing Point, under the protection of Government besides several others, which present the means of the youth receiving suitable educations. And as those who manage them are attentive to their scholars, they make a considerable progress in the common rudiments of learning. Nor are the parents in general backward of availing their children of these advantages.[24]

As a state school, noted historian Vernon W. E. Goodin, ‘it was directly controlled by the governor,’ teachers were ‘appointed to the office either by the King or by the Colonial Governor, and could only be dismissed by the same authority.’[25]

The Kennys opened their school ‘at No. 8, on the Rocks, at the back of the Residence of Mr. Henry Kable’ (Harrington Street) on 30 October 1805.[26] The advertisement announcing the school’s opening appeared in the Sydney Gazette on 6 October and informed ‘Parents and Guardians who may please to place their Children under their tuition’ that they ‘may rely on the strictest attention to their speedy improvement in Reading, Writing, Vulgar and Decimal Arithmetic, Menturation, and Book-keeping according to the Italian mode.’[27] Goodin described the school’s location at Talla-wo-la-dah (The Rocks) as one ‘which at that time had a mixed population of the very best and the very worst in Sydney. The high ground which in much later years became a slum area was then highly popular with the social elite on account of the views and the elevated and convenient situation.’[28]

Ten months later, on 12 August 1806, William Bligh arrived to replace King as Governor of the Colony of New South Wales. It was on this same day that King mentioned the Catholic school at Cadi (Sydney) in his report on the ‘Present State of His Majesty’s Settlements on the East Coast of New Holland, called New South Wales.’[29] Yet Goodin claimed that the Kenny School was ‘given up’ ‘with or without reason…as soon as Bligh became Governor,’ implying that the newly arrived Governor Bligh, less liberal than his predecessor, must have refused to continue supplying government funding to an Irish Catholic school or, at least, dismissed the Kennys as its masters, as it was within his power to do. Since Goodin did not cite any primary evidence to support a precise time for when the Kenny School ceased operating, it is possible it continued for considerably longer, because a general muster noting each person’s employment status, taken on the same day of King’s report and Bligh’s arrival, tells a different story to the one Goodin offered. John Kenny was mustered as a ‘self-employed schoolmaster’ in an unknown location, while his younger brother James was already employed, presumably as a common labourer, by John Ruffler, an emancipated First Fleet convict who had a thirty-three-acre grant at ‘Mulgrave Place,’ near present-day Bardo Narang (Pitt Town) in the Hawkesbury region.[30] The discovery that it was John Kenny who was still employed as a schoolmaster whilst James was already a labourer in the Hawkesbury emphasises a peculiarity in Goodin’s ‘History of Public Education in New South Wales before 1848’: Goodin does not acknowledge John Kenny’s existence at all. Only the younger brother James is named and credited as the first Catholic School teacher in the colony and Australia, and as ‘giving up’ the school at Talla-wo-la-dah (The Rocks), yet from the outset, as the 1805 advertisement made clear, like everything the Kenny brothers undertook (including robbery!), the school had been very much a joint venture, and it was John—not James—who continued teaching the longest in this period.

The possibility that John Kenny the Catholic schoolteacher may have been the gibbetted murderer only intensifies when we get to know the murder victim a little better.

The Victim: ‘A Decent, Inoffensive Woman’

Mary Smyth, a convict per Britannia (1797), was ‘a decent, inoffensive woman who…followed the avocation of an instructress on the Brickfield Hill.’[31] An ‘instructress’: a female teacher, and an Irish one at that! Granted, the Brickfield Hill, an area of the colony devoted to brick-making and now part of Surry Hills, was definitely not Talla-wo-la-dah (The Rocks), where the Kenny School had operated. On the other hand, to be able to secure employment as an instructress anywhere in the colony, Mary must have had some level of education and, while Goodin noted that ‘Private tutors, both men and women, were not a novelty,’ a literate Irish female was undoubtedly less common, given that impoverished Irish female convicts typically would have had limited or no access to education.[32] This unusual mix of a marketable skill and Mary’s ethnicity increases the chances that she ended up teaching or assisting at the Kennys’ ‘niche’ school for Irish Catholic children. (Mary’s religion is unknown, but there is a good chance she was Catholic, too). So, let us hypothesise for a moment that Mary Smyth did indeed previously work as a teacher at the Kenny School at Talla-wo-la-dah (The Rocks), or at the last undisclosed location John Kenny was working as a self-employed teacher in August 1806. If Goodin was correct in his claim that the school closed as soon as Bligh’s governorship commenced or soon after, then Mary would have been obliged to seek work elsewhere in Cadi (Sydney), such as the ‘Brickfield Hill,’ perhaps as a private tutor or in another school, be it private or state-aided. Even in this scenario, some sort of association with her fellow Irish schoolteachers, the Kennys, would have likely continued.

We do not know how old Mary Smyth was at the time of her death, nor do we know her birthplace. In fact, even Mary’s trial date is impossible to determine. As with the case of the multiple John Kennys, there was another woman on the same ship as Mary Smyth with the same name who was tried in the same city of Baile Átha Cliath (Dublin), within a year of Mary’s own conviction. Yet these basic biographical details do not, in the end, tell us who she was at her very core. We gain a far greater insight into the kind of person Mary Smyth was in her actions and in the conversations various people had with her on her final day, all of which is in the account of how she came to be horrifically murdered and wickedly disposed of by her killer.

The Murder

Mary Smyth was fiercely independent and gutsy—rather too gutsy, as it turned out. On Saturday 10 January 1807, a very determined Mary donned her patterned cotton gown with its matching cloth-covered wire buttons at the wrist, put on her nankeen walking shoes, tied up a pair of leather shoes in a handkerchief, clasped her parasol with her other hand, and set off—she was a lady on a mission.[33] No one would steal from her and get away with it: she would seek the perpetrator out herself, confront them, and demand that they return what was rightfully hers. She said as much to James Phelan when she was at his Cadi (Sydney) home that day, adding that she suspected John Kenny had robbed her, and that she was therefore heading out to Parramatta in quest of ‘some’ of her treasured ‘articles.’[34] She wholeheartedly believed she could ‘recover part of her property’ thus ‘without recourse to harsher measures.’[35] Whether or not Phelan harboured any reservations about Mary’s plan is unknown; but even if he did, he nevertheless accompanied her to the passage boat and waved her off.

On the boat to Parramatta, Mary found another willing ear in Samuel Terry, a convict who would go on to become Australia’s richest-ever man.[36] Mary told Terry that she also ‘intended going to Hawkesbury after some of the things that had been taken from her.’[37] On hearing this, Terry offered her ‘a passage up in his cart, which was going from Parramatta to Hawkesbury next day,’ and Mary gratefully accepted, though she would never have the chance to actually make that journey.[38]

Read in combination, Phelan and Terry’s depositions seemingly indicate that Mary believed two individuals had robbed her ‘some months before,’ and that ‘some’ of her property was with one of them who was now at Parramatta (John Kenny), and ‘some of the things taken from her’ were with the other ‘suspect,’ in the Hawkesbury.[39] Is it sheer coincidence that the killer John Kenny was in Parramatta, and that the Hawkesbury was precisely where John Kenny the schoolteacher’s brother James was then working as a labourer for John Ruffler? Might the Kenny brothers have returned to their robbing ways, despite the major coup of securing government support to teach in their very own Catholic school? Did they commit one last robbery together, this time on a fellow teacher? Is this what prompted James to suddenly leave their school at Talla-wo-la-dah (The Rocks) within months of the school’s grand opening to work as a common labourer in a remote, rural location? The newspaper reports of the criminal proceedings do not name the individual Mary was planning to visit at the Hawkesbury, perhaps solely because she never made it that far, or perhaps because, based on Terry’s deposition, Mary never divulged to him that she suspected the Kennys. If she had named them, Terry might have reacted differently to what transpired when they both reached Parramatta.

Once in Parramatta, Terry inquired ‘where [Mary] should be found’ the next day, so he knew where to collect her for the journey to the Hawkesbury.[40] Mary replied that ‘she intended to sleep either at the house of Margaret Rees or John Kenny.’[41] Observing John Kenny ‘at his own gate’ Terry ‘pointed out the house to her,’ after which John Kenny ‘advance[d,]…t[ook] her cordially by the hand, [and] lead [sic] her into his house.’[42] Terry would later recall under oath, ‘[A]t parting, [Mary Smyth] anxiously requested [Terry] to call there for her the next morning, or at the house of Margaret Rees.’[43] He would see poor Mary Smyth the next morning, albeit as an unrecognisably disfigured, discarded corpse.

The same night, Mary Smyth and John Kenny visited the house of the previously mentioned Margaret Rees, a convict woman per Experiment I (1804) who, according to the muster taken the previous year, was employed at the Factory Above the Gaol. Whilst at Rees’s house, and apparently when John Kenny was not within earshot, Mary ‘recit[ed] the circumstance of the robbery, her suspicion of [John Kenny],’ and, further, that she had already sufficiently confirmed his guilt, for ‘she had seen the prisoner wear about his neck a handkerchief which she knew to be part of her property.’[44] Although Margaret Rees pleaded with Mary Smyth to stay with her overnight, she declined and ‘persisted in her determination…to go home with [John Kenny], and to sleep at his house…with a view of recovering more of her property.’[45] At some stage during the visit, Rees recalled, Kenny confirmed the accommodation arrangements and ‘seemed very anxious to get her away.’[46] Maybe Mary Smyth had used some of her feminine wiles to make him think she was there for him that night, rather than for her stolen items. That Mary was still prepared to sleep under John Kenny’s roof when she was sure he had robbed her either says a lot about how well she felt she knew John Kenny, how well he hid his dark self, or how invincible she thought she was. Because, otherwise, a woman who had been a convict herself and, therefore, would have been ‘worldly wise’ could not have so seriously underestimated what John Kenny was capable of: he was a bit light-fingered but, after all, so was she, to say nothing of the rest of the colonial population! All she wanted was to retrieve her property; she had no intention of getting anyone into trouble by taking ‘recourse to legal measure.’[47] Everything could be settled amicably between herself and the Kennys. As the first of several blows came down upon the back of her head, did Mary have time to realise her mistake? Quite possibly, because despite these blows leaving ‘several wounds on the back of the head,’ ‘a great quantity of blood’ in Kenny’s bedroom fireplace, and a bloody trail in a direct line from the murder scene to where Kenny disposed of the body, Surgeon Mileham would later note that Mary’s skull did not appear to have been fractured, so it was his opinion that the head injuries were not what killed her.[48] It would have been better if they had. Most distressingly, Kenny had dragged the unconscious, bleeding, yet still very much alive Mary into his fireplace ‘to consume the unhappy object of [his] depravity,’ with a view of erasing her identity and thus ‘conceal[ing his] guilt.’[49] Mary either perished there in the flames or died slowly from her extensive burns, perhaps as he moved her from his house across undeveloped land (probably present-day Parramatta Public School) or, chillingly, maybe only as he threw the dirt over what used to be her face.[50]

A woman named Eleanor Clavers made the terrible discovery of Mary’s ‘partly covered’ body early the next morning, Sunday 11 January 1807, ‘on or near the grounds’ of Surgeon D’Arcy Wentworth, most likely on the border of his grant and what later became the site of the Military Barracks.[51] Around eight o’clock the same morning, Parramatta’s Chief Constable Francis Oakes informed Wentworth about the discovery of a dead body on his property and both proceeded to the spot.[52] News travelled fast in the small town, so by the time they reached the site practically every other Parramattan had beaten them there:

[U]pon the earth being removed from off the covered part of the body it proved to be that of a woman, burnt and so much disfigured that none of the numerous persons assembled could call to recollection who she was until one of them [Samuel Terry] mentioned that among the passengers arrived from Sydney in the boat the day before was a woman, that had gone to the house of Kenny,…which was near at hand. That Kenny, whose house was so close to the spot, should be almost the only one in the neighbourhood who was absent from the melancholy spectacle struck [Wentworth’s] imagination with much force.[53]

Wentworth and Thomas Hobby walked from the deposition site towards the home of the prime suspect, which was only ‘a hundred yards’ distant.[54] Along the way, they noted ‘a ditch on the side of which were the evident traces of a man’s boot (proceeding towards where the body lay).’[55] The murderer had clearly ‘slipped in ascending it, as it was rather steep.’[56] He must have dropped Mary in the process, as ‘a quantity of blood was visible’ there, too.[57] Crucially, ‘the footstep continued to the paling of the house which [Kenny] inhabited,’ but the door was locked.[58] After causing the door to be opened, Wentworth found within a ‘cleanly swept’ apartment ‘but in one corner some tinder was found, which proved to have been cotton cloth.’[59] These ‘scraps of tinder retained the outlines of their original pattern, which corresponded with the gown found on the deceased,’ and, as James Phelan would later testify under oath, were also a match for the cotton gown Mary was wearing when she boarded the passage boat to Parramatta, and to her death.[60] A piece of wire found on the scene, which had once been part of the cloth-covered wire buttons on her gown, was also positively identified by Phelan as being ‘of the same size.’[61] Casting his eye to an adjoining passage, Wentworth found ‘several spots of blood were visible, over which dirt had to all appearance recently been thrown.’[62] Elsewhere in the house, Wentworth found a shirt that had been ‘newly’ spot-cleaned, no doubt to remove blood splatter.[63] Chief Constable Francis Oakes likewise searched the premises, noted the ‘direct line…of blood…from where the body lay towards the prisoner’s house,’ the ‘great quantity of blood in the bedroom fireplace,’ and more burnt or blood soaked remnants of Mary’s life scattered about: ‘several pieces of scorched leather about the room and passage,’ presumably the leather boots Mary had carried in a handkerchief all the way from Cadi (Sydney), ‘and a handkerchief stained with blood…in the bedroom.’[64] Town gaoler Richard Partridge recovered ‘the brass ring’ of Mary’s parasol ‘on a dunghill close to the house.’[65]

When they went to apprehend John Kenny for the murder of Mary Smyth, they found him where one might expect to find a good Catholic schoolteacher on a Sunday morning: ‘at church.’[66]

‘The Most Direful Aggravation of a Horrible Offence’

John Kenny was ‘fully committed’ by the Coroner’s Verdict.[67] On Monday 12 January 1807, Mary Smyth was given the decent Christian burial she deserved in the parish of St. John’s, Parramatta, and Kenny came under the watchful eye of gaoler Richard Partridge at the Parramatta Gaol (present-day Prince Alfred Square) whilst awaiting his trial.[68] At Sydney’s Court of Criminal Jurisdiction ten days later, on Thursday 22 January, with such damning evidence before them, the Court, ‘with little hesitation found the prisoner Guilty.’[69] The Judge Advocate, Richard Bowyer Atkins, ‘proceeded to pass sentence of condemnation,’ and showed no mercy to one who had ‘mercilessly tak[en] the life of a fellow creature, incapable of defending herself against the violence of an assailant from whose superior strength she could have no retreat.’[70] He first apprised [John Kenny] that his situation was the most wretched and inconsolable to which human nature could be reduced by any act of enormity,’ [for b]y his crime, he had violated the Laws of God! the voice of Nature, Reason, and Mankind have ever demanded,’ “that whosoever sheddeth Man’s blood, by Man shall his blood be shed.”[71]

Yet even among murderers, John Kenny was deemed to be one of the very worst. He had robbed Mary Smyth of her life and sent her ‘with all her crimes upon her head, before the Supreme Tribunal,’ but his case was ‘fraught with the most direful aggravation of’ what was already ‘a horrible offence’: he ‘had daringly presumed to torture & destroy a fellow creature.’[72] He had apparently burnt her alive, might have even buried her alive, and had almost succeeded in erasing her identity, too. Such a crime could only have been committed by one with ‘a disposition, savage, sanguinary, and unrelenting, and precluded him the pity it had not been in his own ‘nature to bestow.’[73] John Kenny, a man who showed no respect for life, and even less for a corpse, was thus condemned to suffer the same, for, as we know, he lived at a time when his society happened to have a gruesome punishment to fit his shocking crime. After ‘pathetically admonish[ing] Kenny to repentance, to implore the forgiveness of the Great Avenger of Crimes, and to supplicate that his heart might be cleansed from the corruptness that…seized upon its noblest faculties,’ Judge Advocate Atkins ‘passed the awful sentence, which doomed’ Kenny to be hanged at Cadi (Sydney), then ‘sent to Parramatta to be hung in chains.’[74] In accordance with the common British practice of gibbetting bodies in a highly visible place with a lot of foot traffic and, preferably, ‘as close to the crime scene’ as possible, Kenny’s dead body was displayed near both the house in which he killed Mary Smyth and the place where he disposed of her body.[75]

Thanks to William Hosking, we know that Kenny the killer (like Kenny the schoolteacher) had two children: a girl and a boy who were old enough to be apprenticed.[76] With nowhere else to go, the daughter was sent to the Orphan Asylum in Cadi (Sydney).[77] Small wonder, then, that the whole sordid tale proved to be so memorable to William Hosking: his own parents, the pious Methodists John and Ann Hosking, took over as Master and Matron of the Female Orphan Asylum in early 1809. No doubt the Hoskings, as the new leaders of an orphan school in Cadi (Sydney), found all this a scintillating bit of gossip about what increasingly appears to have been their Irish Catholic school-teaching counterparts, not to mention about one of the children then under their care. They need not have been too smug. According to some, even under the Hoskings’ direction, the orphanage really was no better than ‘a bawdy house’ since its position in the centre of town and, of all places, opposite the guard house, meant the girls who were not fortunately married invariably turned to prostitution upon leaving.[78] Nonetheless, if the schoolteacher’s then twelve-year-old daughter Ann Kenny was the murderer’s daughter who was admitted to the Orphan Asylum in early 1807, then it seems Ann ultimately transitioned from the Hoskings’ Orphan Asylum to the outer world with her character intact, because in October 1814, when she would have been around nineteen years old, she was no prostitute on the streets of Cadi (Sydney): she was mustered at Parramatta as a colonial-born servant to the Reverend Samuel Marsden and his wife Elizabeth.[79] As for the murderer’s ‘poor boy’ (possibly the schoolteacher’s son Morris), William Hosking informs us that he toiled each day as an apprentice at the Lumber Yard, located on ‘Pitt Row’ (Rumsey Rose Garden, Pitt Street)—just a fifteen-minute walk from where his disgraced, dead father was so obscenely displayed.[80]

The story would prove to be one of the highlights of William Hosking’s colonial boyhood when he, at the age of twenty-seven in far-off England, wrote about his memories of Cadi (Sydney) and Parramatta and published them anonymously in The Australian. William was to be disappointed by the story of Parramatta’s gibbetted murderer in only one respect. Though criminals were known to hang in their iron cages for years or even decades, a mere two years after the foul deed of murder and the subsequent execution of John Kenny, young William did not have the dubious pleasure of gawking at it himself, for the body was no longer hanging from its gibbet, a stone’s throw from where Hosking holidayed with the Hassalls.

As was often the case with criminals condemned to the gibbet, their bodies were liable to be stolen by friends or family members who wished to spare them from being reduced to a ghastly spectacle and to give them a proper burial.[81] Such allies were known to intercept those transporting the executed criminal’s corpse from its hanging site to its gibbeting site.[82] Obviously this did not happen to Mary Smyth’s murderer on the long journey from Cadi (Sydney) to Parramatta by cart, as William Hosking confirms he was indeed gibbetted at what became the Lancer Barracks site. If the locals were to be believed, this lack of interference during the transportation of Kenny’s corpse was no reflection on his family members’ loyalty to his memory for, according to them, when John Kenny’s body went missing ‘a short time’ after it was gibbetted, they surmised that his lad had gone ‘alone one night, took it down and buried it’ himself.[83] Just what the Old Parramattans considered ‘a short time’ for a body to be gibbetted is unclear, because they likely expected it to hang there for years if not decades until nothing was left but some exposed bones rattling against their iron cage, ghoulishly reanimated by an occasional gust of wind. The body may well have disappeared suddenly, without any fanfare, but probably not by the Kenny boy’s hands. It is not that bodies were never ‘rescued’ from gibbets; they clearly were, because even as late as 1832 anyone caught stealing a gibbetted corpse in England automatically earnt themselves a sentence of seven years transportation.[84] From Sarah Tarlow’s work on the ‘technology of the gibbet,’ however, we learn that the usual height of the contraption was in the vicinity of ten-metre poles and even higher, and that it had a ‘substantial quantity of iron’ in the chains; this, combined with the dead weight of the body, surely precluded a young boy from having been able to singlehandedly complete this grim task.[85] If the lad were involved at all, he would have needed the help of a very sympathetic adult—his ‘Uncle Jim’ (James Kenny), perhaps? The burial registration for a ‘John Kenny’ at St. Philip’s in Cadi (Sydney) on 5 May 1807 may instead indicate that the killer, having been gibbetted at Parramatta since late January that year, was sufficiently disintegrated to be permitted a discreet burial in Cadi (Sydney), away from the prying eyes of the more invested Parramattans, if only out of the interests of the public’s health.[86]

* * *

The case of Mary Smyth and her killer John Kenny is a fascinating one for those interested in how religion and the law intersected to provide judges with two gory options for punishing a murderer in this world and the next, whilst simultaneously ‘harnessing the power’ of his corpse to deter others from committing murder. Since gibbetting cases in the British context have received very thorough academic attention in recent years, however, the value of this case lies more in it being one of only a few examples of this post-mortem punishment in the British penal colony of New South Wales, where gibbetting remained an option for three whole years after it was abolished in Britain in 1834.[87] Even a brief discussion of a few of the legally sanctioned colonial gibbetting cases above has revealed that the patterns experts have uncovered in Britain were repeated in the colonial setting. According to Sarah Tarlow, for example, gibbetting was rare in Britain overall, with only 9.6% of people in Britain executed for murder between 1752–1832 suffering the punishment compared to the more than 80% of people who ended up dissected on ‘the anatomist’s slab,’ and this was certainly the case in New South Wales, too.[88] Other experts have also noted that in Britain, the punishment was typically reserved for those who committed aggravated offences. An examination of the wording used by the court when summing up the case against John Kenny and delivering his sentence reveals that this was true here as well, as he qualified for gibbetting on the basis that he was guilty of ‘the most direful aggravation of’ what was already ‘a horrible offence.’[89] The rarity of the punishment (even in a penal colony where the majority of the population were here because they were already judged to be rather bad), makes it all the more important that we positively identify John Kenny the killer, or that we at least have a greater awareness of this 1807 murder case, because it is clearly a significant one in the colony’s legal history as well as in Australian history in general.

Still, what distinguishes colonial gibbetting from British cases is that in New South Wales the statistics may never tell the whole story, for the simple fact that not every reported gibbetting case here was the result of criminal proceedings. I say ‘reported,’ because while multiple contemporary sources record that Captain Paterson did indeed order armed soldiers to kill and gibbet Bidjigal People in 1795, and Judge Advocate David Collins confirms he received reports that ‘several…were killed in consequence of this order,’ Collins also noted that ‘none of their bodies being found (perhaps if any where killed they were carried off by their companions,) the number could not be ascertained,’ indicating that the gibbetting part of the order was not adhered to on this occasion. It is only in the account of Reverend Thomas Fyshe Palmer that this particular instance of gibbetting is ‘reported’ as something that definitely came to pass and, as Stephen Gapps has argued, he was most likely writing from second-hand information, not to mention with a serious axe to grind when it came to British authorities, given that he had been transported as one of the five so-called ‘Scottish Martyrs’ as a political prisoner:

The Natives of the Hawkesbury…lived on the wild yams on the banks. Cultivation has rooted out these, and poverty compelled them to steal Indian corn. The unfeeling settlers resented this by unparalleled severities. The blacks in return speared two or three whites, but tired out, they came unarmed, and sued for peace. This, government thought proper to deny them, and last week sent sixty soldiers to kill and destroy all they could meet with, and drive them utterly from the Hawkesbury…They [the soldiers and settlers] came upon [the natives] unarmed, and unexpected, killed and wounded many more. The dead they hang on gibbets, in terrorem…The people killed were unfortunately the most friendly of the blacks, and one of them more than once saved the life of a white man.’[90]

Hard as it is to know now for certain which version of these events is correct, the existence of Palmer’s account means it is possible that, in some parts of the colony, it may have only been rare to see a white person hanging from a gibbet. But was Australia’s first Catholic school teacher one of them?

From the evidence currently available, it would appear Australia’s first Catholic schoolteacher did take the life of the inoffensive Mary Smyth. However, let us review that evidence and take one last opportunity to test any arguments that may still be raised to the contrary. Some researchers have claimed John Kenny the schoolteacher could not have been the man on the gibbet in Parramatta in January 1807 for the following reasons: they argue that from August 1806 the schoolteacher was a settler in the Hawkesbury; that he helped his brother, James, to open another school at Wangie (Wilberforce) in Dharug Country around 1807; and he was fatally bitten above the instep by a black snake ‘supposed to be eight feet in length at least’ at Wangie (Wilberforce) in February 1814.[91] Such an argument certainly succeeds in building a case that John Kenny the Catholic schoolteacher was nowhere near Parramatta at the time of Mary Smyth’s murder and, thus, could not have been the perpetrator. Nevertheless, there are a number of problems with these claims. John Kenny the Catholic schoolteacher per Boddingtons (1793) was still mustered as a teacher in August 1806, so he could not have also been a separate John Kenny per Britannia (1797) mustered as a settler renting from ‘Bowman’ at ‘Richmond Hill,’ Marrangorra (Richmond) in the Deerubbin (Hawkesbury) region on the same day. The notion that the school founded by John’s younger brother James at Wangie (Wilberforce) around 1807 was another joint venture by the Kenny brothers appears to be little more than an assumption, as no evidence was offered to corroborate the claim, and others who have researched the history of the school have instead stated that Second Fleeter Paul Bushell helped James Kenny in that enterprise, making no mention of a brother named John Kenny being involved. Finally, a transcription of the Reverend Robert Cartwright’s entry in the St. Matthew’s burial register at Wangie (Wilberforce) confirms that ‘the other John Kenny’ per Britannia (1797)—that is, the one who was not a schoolteacher—was the Hawkesbury settler killed by the black snake at Wangie (Wilberforce) in 1814.[92] If the transcription of the St. Matthew’s burial register is correct, then it seems it was pure coincidence that John Kenny the settler was based in the same region of the Hawkesbury as James Kenny, the surviving Kenny brother who established a school there after the murderer John Kenny’s execution and gibbetting at Parramatta. Admittedly, however, colonial records being the fragmentary and problematic sources that they are, it cannot be discounted that a third person may have been unofficially going by the name ‘John Kenny’ and murdered Mary Smyth at Parramatta instead. The fact that the convicted robber and Catholic schoolteacher John Kenny per Boddingtons (1793) disappears from the historical record at the same time Mary Smyth’s thief and murderer was executed is, however, difficult to ignore. One thing is for sure; if correct, then the case of John Kenny and Mary Smyth makes for a very dark beginning to the history of Catholic education in Australia.

CITE THIS

Michaela Ann Cameron, “A Murderer’s Banes in Gibbet Airns,” St. John’s Online (2020), https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/mary-smyth, accessed [insert current date]

References

- Rachel E. Bennett, Capital Punishment and the Criminal Corpse in Scotland, 1740–1834, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

- Owen Davies, Elizabeth T. Hurren, Sarah Tarlow (eds.), Book Series: Palgrave Historical Studies in the Criminal Corpse and its Afterlife, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015–2018).

- Vernon W. E. Goodin, “Public Education in New South Wales before 1848,” Royal Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, Vol. 36, (1950).

- Albert Hartshorne, Hanging in Chains, (New York, N.Y.: Cassell Pub. Co.,1893).

- William Hosking, “Terra Incognita. No. 1,” The Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Friday 26 October 1827, p. 4.

- William Hosking, “Terra Incognita. Concluded,” The Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Wednesday 31 October 1827, p. 4.

- Peter King, Punishing the Criminal Corpse, 1700–1840: Aggravated Forms of the Death Penalty in England, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

- New South Wales Government, “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

- Sarah Tarlow, The Golden and Ghoulish Age of the Gibbet in Britain, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

- Sarah Tarlow and Emma Battell Lowman, Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

- Criminal Corpses: Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse (https://criminalcorpses.com, 2020)

- Sarah Tarlow and Zoe Dyndor, “The Landscape of the Gibbet,” Landscape History, Vol. 36, No. 1, (2015): 71–88.

NOTES

[1] The title for this essay, “A Murderer’s Banes in Gibbet Airns,” is written in Scots English and is a direct quotation from the famous Robert Burns narrative poem “Tam o’Shanter” (1791). See “Tam o’Shanter,” in Robert Burns, The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1910), pp. 241–8. William Hosking referenced “Tam o’Shanter” himself in his recollections of first arriving in the penal colony, but he did so in relation to another gibbetted convict: Francis Morgan at Pinchgut. Hosking had arrived in the colony per Æolus (1809) with his parents, John and Ann, and two brothers, John Jnr and Peter Mann, just a couple of months earlier on 26 January 1809, having been driven to the penal colony by his father’s ‘ruin’ and subsequent willingness to accept ‘the first thing that presented itself’—‘an employment of small consequence, and of smaller emolument, in the distant colony’ as Master and Matron of the Orphan Asylum in Cadi (Sydney). See William Hosking, “Terra Incognita. No. 1,” The Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Friday 26 October 1827, p. 4.

[2] William Hosking, “Terra Incognita. Concluded,” The Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 – 1848), Wednesday 31 October 1827, p. 4. All identifying details are censored in Hosking’s account; however, it is clear that it was Hassall House in which he spent his holidays, as it would have been the only house with such a grand, established garden on the convict-hut lined street in early 1809. Moreover, his description of the kinds of trees and plants in the garden is very similar to the description the Hassalls’ grandson, James S. Hassall, would later provide: “My father [Thomas Hassall] had an old-fashioned brick house opposite the school [Harrisford], built by the Government for his father [Rowland Hassall]—I think at the time when he had charge of the colonial cattle-stations, then all Government property. There was a great mulberry-tree in the garden and the largest English oaks in the colony were there. The property comprised about four acres of land. On a Guy Fawkes’ Day, we used to make large bonfires from the dead lemon-trees that had formed a hedge around it.” See James S. Hassall, In Old Australia: Records and Reminiscences from 1794, (Brisbane: R. S. Hews & Co., 1902), pp. 18–9.

[3] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842),Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. See also: JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[4] “St. Athanasius’s Creed” in The Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments, and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, according to the Use of The Church of England: Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, pointed as they are to be sung or said in Churches, (Cambridge: John Baskerville, 1762).

[5] “The First Sunday in Advent. The Collect,” The Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments, and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, according to the Use of The Church of England: Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, pointed as they are to be sung or said in Churches, (Cambridge: John Baskerville, 1762). According to folk belief, a corpse had to have its skull and long bones to be considered ‘intact.’

[6] Sarah Tarlow, “The Technology of the Gibbet,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 4, (2014): 668–9.

[7] The Murder Act 1751 (25 Geo 2 c 37), was passed into law in 1752, so it is sometimes also known as the Murder Act 1752. See Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), Ordinary of Newgate’s Account, 2 July 1752 (OA17520702), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?name=OA17520702, accessed 27 October 2020; “The Murder Act 1752,” Criminal Corpses: Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse, https://www.criminalcorpses.com/murder-act-timeline, (2016), accessed 27 October 2020.

[8] British criminal records in this period reveal a similar pattern. See “Hanging in Chains: The Criminal Corpse on Display,” in Rachel E. Bennett, Capital Punishment and the Criminal Corpse in Scotland, 1740–1834, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), p. 199.

[9] British criminal records in this period reveal a similar pattern. See “Hanging in Chains: The Criminal Corpse on Display,” in Rachel E. Bennett, Capital Punishment and the Criminal Corpse in Scotland, 1740–1834, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), p. 199.

[10] British criminal records in this period reveal a similar pattern. See “Hanging in Chains: The Criminal Corpse on Display,” in Rachel E. Bennett, Capital Punishment and the Criminal Corpse in Scotland, 1740–1834, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), p. 188. See also “‘Hanging not Punishment Enough’: Attitudes to Aggravated Forms of Execution and the Making of the Murder Act 1690–1752,” in Peter King, Punishing the Criminal Corpse, 1700–1840: Aggravated Forms of the Death Penalty in England, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 29–75.

[11] John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress cited in Albert Harthshorne, Hanging in Chains, (New York: Cassell Publishing Company, 1893).

[12] Albert Harthshorne, Hanging in Chains, (New York: Cassell Publishing Company, 1893), p. vi.

[13] Mattewanye, also spelt MaDAwanyA and Muddawahnyuh. See Harold Koch and Luise Hercus (eds.), Aboriginal Placenames: Naming and Re-naming the Australian Landscape, (Canberra: ANU E Press, 2009), p. 66.

[14] Michaela Ann Cameron, “Prince Alfred Park, Parramatta,” Dictionary of Sydney, (2014), https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/prince_alfred_park_parramatta, accessed 27 October 2020.

[15] There are a couple of reasons for the murderer’s anonymity. One is that my starting place for this murder tale was not the murder case itself but William Hosking’s account, which was semi-anonymously signed “W—— ——G,” with all identifying details such as names, locations, and ship names likewise concealed. His account describing the gibbet location ‘where the military barracks now stand’ confirmed that the murder in question had to have been prior to 1819 (the year the Military Barracks were completed). William Hosking ultimately provided enough factual details to make identifying him, his family, and the ship they arrived on possible, which then enabled me to use information from the remainder of his account to pinpoint the timing of his Easter visit to Parramatta as 1809, just a couple of months after his family arrived per Æolus (1809), allowing me to focus on murders in Parramatta prior to Easter 1809 exclusively. Hosking stated that the murder occurred ‘recently’ in the house ‘right next to’ the home of the family friend with whom he was staying that Easter, on George Street (then known as High Street) Parramatta. Hosking also described a very established and stunning garden at the home in which he stayed. In this period, High Street / George Street, Parramatta was largely lined with convict huts. The famed gardens of the Red Cow Inn had not yet been created at the time of the murder or Hosking’s first Easter visit, so, to my mind, the family friend with the beautiful home and extensive, established gardens and orchards, including a ‘mulberry arbour,’ was narrowed down to just one: the Hassalls’ home, which once stood at 106 George Street, opposite Harrisford. My theory that it was Hassall House was further supported by primary source evidence describing the garden, including the ‘mulberry arbour’ in archaeological reports of Hassall House. The gibbet on the site of Lancer Barracks does, indeed, position the gibbet in uncomfortably close proximity to Hassall House.

[16] “Baptism of ANN KENNY, 26 May 1795,” St Philip’s Church of England, Sydney NSW: Church Register – Baptisms, ML ref: Reel SAG 90; Volume entry number: 343, Biographical Database of Australia (https://ww.bda-online.org.au, 2020). No marriage record has been found, but the fact the mother’s surname was recorded as Kenny at a time when unmarried couples were usually entered into the register with their own surnames may indicate that a marriage had taken place.

[17] Morris Kenny was born on 11 March 1797, but he was not baptised until 1799. “Baptism of MORRIS KENNY, 22 April 1799,” Parish Baptism Registers, Textual Records, St. John’s Anglican Church, Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia. On this occasion, John’s wife was recorded as ‘Margaret’ rather than Mary. Perhaps it was a different woman, or maybe it was an error by one of the clerks, either at St. Philip’s on Ann’s baptism or at St. John’s on Morris’s baptism. As no marriage record was ever found for John Kenny, it is not possible to say who Mary/Margaret was or whether she might have even arrived in the colony as the free wife of her convict husband.

[18] New South Wales Government, Registers of Land Grants and Leases, Series: NRS 13836; Item: 7/445; Reel: 2560, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia).

[19] Morris Kenny was baptised at St. John’s, Parramatta on 22 April 1799. “Baptism of MORRIS KENNY, 22 April 1799,” Parish Baptism Registers, Textual Records, St. John’s Anglican Church, Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia.

[20] We can even place a John Kenny in the Parramatta township, thanks to an August 1801 document stating that ‘thro a mistake of the Civil Court’ he had ‘been allowed to take out a Writ and’ had ‘treated that Court with great Contempt,’ and was, therefore, ‘very properly Committed’ and ‘Ordered to Government Labour at Parramatta, from which he was before exempt.’ While no ship was recorded for this John Kenny in this piece of evidence, the fact it mentions an ‘exemption’ from Government Labour at Parramatta may explain how the Kenny brothers had managed to obtain land grants at the Field of Mars just four years after arriving as convicts. See “JOHN KENNY, August 1801,” New South Wales Government, Special Bundles, 1794–1825, Series: NRS 898; Reel or Fiche Numbers: Reels 6020–6040, 6070; Fiche 3260–3312; Page: 56, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia).

[21] Later on, convict indents collected much more information on each convict, including tattoos, distinguishing marks, missing fingers, pockmarked skin, complexion, hair colour, eye colour, literacy, marital status, and religion. John’s brother, James Kenny’s entry in the 1828 Census confirms the Kennys’ religion was Catholic. See “James Kenny, per Boddingtons (1793), Age: 57,” New South Wales Government, 1828 Census: Alphabetical Return, Series: NRS 1272; Reel: 2554, (State Records Authority of New South Wales; Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia).

[22] Parliament of Great Britain, Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, An act to relieve, upon conditions, and under restrictions, the persons therein described, from certain penalties and disabilities to which papists, or persons professing the popish religion, are by law subject, 31 George III. c. 32 (1791).

[23] Parliament of Great Britain, Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, An act to relieve, upon conditions, and under restrictions, the persons therein described, from certain penalties and disabilities to which papists, or persons professing the popish religion, are by law subject, 31 George III. c. 32 (1791).

[24] Philip Gidley King, “Present State of His Majesty’s Settlements on the East Coast of New Holland, called New South Wales,” in F. M. Bladen (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. VI.—KING AND BLIGH, 1806, 1807, 1808, (Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer, 1898), p. 152. While Governor King did not explicitly identify the Kenny brothers as the masters of the state-aided first Roman Catholic school in the colony (and hence Australia) in this direct quotation, Goodin states that it was the Kenny School which had been given this honour. Vernon W. E. Goodin, “Public Education in New South Wales before 1848, Part II,” Royal Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, Vol. 36, Part II, (1950): 102.

[25] Vernon W. E. Goodin, “Public Education in New South Wales before 1848, Part I,” Royal Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, Vol. 36, Part I, (1950): 9–10.

[26] “John and James Kenny…,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 6 October 1805, p. 2.

[27] “John and James Kenny…,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 6 October 1805, p. 2.

[28] Vernon W. E. Goodin, “Public Education in New South Wales before 1848, Part II,” Royal Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, Vol. 36, Part II, (1950): 102.

[29] Philip Gidley King, “Present State of His Majesty’s Settlements on the East Coast of New Holland, called New South Wales,” in F. M. Bladen (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. VI.—KING AND BLIGH, 1806, 1807, 1808, (Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer, 1898), p. 152.

[30] “John Kenny; Boddington [sic]; How employed: Self; Condition: FBS [Free by Servitude]; Remarks: Schoolmaster,” Home Office: Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, General Muster 1806, HO10; Piece: 37, (The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England); “James Kenny; Boddington [sic]; How employed: Jno Ruffer; Condition: FBS [Free by Servitude]; Remarks: [none recorded],” Home Office: Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, General Muster 1806, HO10; Piece: 37, (The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England). The same muster accounts for “the other John Kenny,” per Britannia (1797) too: he was mustered as a settler renting from ‘Bowman’ at Richmond Hill in the Hawkesbury on the very same day that John Kenny the Catholic schoolteacher was still mustered as a self-employed teacher.

[31] While recorded as “Mary Smyth” on her convict indents, her name was also recorded as “Mary Smith” in both the newspaper reports on her murder as well as the St. John’s parish burial entry. However, I have opted for the Smyth spelling throughout this essay to differentiate the murder victim from another murder victim in the same collection (Mary Anne Smith). “Sydney,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 18 January 1807, p. 1.

[32] Vernon W. E. Goodin, “Public Education in New South Wales before 1848, Part II,” Royal Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, Vol. 36, Part II, (1950): 94.

[33] Note that the newspaper erroneously stated the date was “Saturday the 9th instant,” when it should have been the 10th. “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. Nankeen shoes were a walking shoe made of fabric, worn in the early nineteenth century. According to American Duchess, “The name “Nankeen” comes from the variety of cotton used to make these boots, originally a pale buff-colored cloth manufactured in Nanjing, China. Shortly after its rise in popularity, Nankeen cloth was “knocked off” in Europe, and made of just ordinary cotton dyed to the characteristic khaki color.” For more see Lauren Stowell, “Introducing and Celebrating Nankeen Regency Boots,” American Duchess Historical Costuming, (2014), https://blog.americanduchess.com/2014/02/introducing-and-celebrating-nankeen.html, accessed 27 October 2020 and Rachael Kinnison, “Lady’s 1810–1820 Nankeen Walking Boots,” Lady’s Repository Museum & Diamond K. Folk Art, (2013) https://ladysrepositorymuseum.blogspot.com/2013/02/ladys-1810-1820-nankeen-walking-boots.html, accessed 27 October 2020. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[34] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[35] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[36] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[37] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[38] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[39] “Sydney,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 18 January 1807, p. 1; “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[40] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[41] Italics in original: “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[42] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[43] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[44] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[45] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[46] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[47] “Sydney,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 18 January 1807, p. 1. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[48] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[49] “Sydney,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 18 January 1807, p. 1. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[50] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[51] Note that Smith Street did not yet exist, nor did Charles Street, so when Hosking stated that the murder occurred ‘in the very next house’ to Hassall House, it was most likely in the nearest hut on High Street (George Street), in the vicinity of Perth House and Stables at 85 George Street, Parramatta, which was not built at the time (it was built decades after the murder, in 1841). The murderer, therefore, likely hauled the body from the site of present-day Perth House over ground that is now occupied by Parramatta Public School, into the area that later became the Lancer Barracks site, which is, indeed, on the border of D’Arcy Wentworth’s old grant. A brief search has not located any information about an Eleanor Clavers. It is likely that the newspaper reporter recorded her name incorrectly.

[52] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[53] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[54] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[55] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[56] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[57] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.

[58] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 25 January 1807, p. 2. “JOHN KENNY, Murder of MARY SMITH,” New South Wales Government, Criminal Court Records index 1788–1833: Appendix A: Schedule of prisoners tried, 1788-1815 – Court of Criminal Jurisdiction: Minutes of proceedings, 1788–1815, Reel 2651; 2700 [5/1149]; Page: 337, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX92680, accessed 27 October 2020.