Members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are advised that this essay contains names of deceased Aboriginal People.

Whitechapel Road, London, 1783

A little after five o’clock on the evening of 19 March 1783, Ann Camp was in bed sick with a fever in the house she shared with her mother on Whitechapel Road.[1] The feverish girl was quite alone at the time, as her mother had stepped out to fetch them both ‘a bit of supper.’[2]

‘I heard our bitch making a terrible noise in the garden. I knew she would not bellow at any body but strangers…and when I heard the noise, I crawled up as well as I could [to the window], and looked through…’[3]

Hanging upon the line in the garden, Ann saw some personal items her mother had washed for her and left to dry. Also allegedly part of this tableau, however, was a man unknown to Ann who quickly tore down the line and carried off her belongings.

‘I was so weak, I could not get out to cry Stop thief! before he was gone; he broke three pales and got out.’[4]

The wrongdoer had likely made a quick getaway via the alley located close to the destroyed palings. In the course of this incident, Ann had been dispossessed of a linen shift and linen apron, valued at three shillings each, along with one pair of cotton stockings and one pair of linen coversluts, both worth sixpence each.[5] None of these items were ever seen again. All that the discerning thief had left Ann was ‘an old cloth upon the line’ that was not ‘worth taking.’[6]

Three weeks later Ann, much recovered, was on her way out her door and saw the same man ‘at the very same pales, where he got over before.’ She made no attempt to approach or say anything to him, ‘for there were a parcel of men playing at skittles.’[7] Yet, upon seeing Ann ‘he run away as fast as he could,’ which Ann took as unequivocal evidence of his guilt.

The Old Bailey

Richard Partridge was the man Ann positively identified as the guilty party. At his trial at the Old Bailey on 30 April 1783, Partridge made the case that Ann Camp was not a credible witness, citing as evidence her feverish state and inconsistent testimony:

‘This witness said before the Justice, she had been light headed for two or three days…she could not be positive that I was the person, then afterwards she said, I can swear to him; then said the Justice, I must commit him; then says she, you must not commit him.’[8]

When asked to explain why he, an innocent man, would run away like a guilty one, then, Partridge simply said, ‘I did not run away from her; there is a common necessary down there, and I went down there [to make use of it].’[9] Partridge wound up his defence with the piteous statement:

‘I have not a friend in the world.’[10]

The Court, evidently unmoved and unimpressed with his defence, found him ‘GUILTY’[11] of purloining ladies’ laundry and sentenced him to seven years transportation. He was approximately 24 years old.

Mutiny on the Swift

In August 1783, four months after his trial, Partridge was one of 143 male and female convicts aboard the Swift, bound for America. Not that the independent United States of America was suddenly willing to return to the pre-Revolutionary practices of accepting Britain’s dregs by the shipload. Indeed, the Treaty of Paris that would officially end the American Revolutionary War was still a month away. In any case, it was wishful thinking on the part of the British that once ‘tranquility was restored to America’[12] they could cease relying on the ‘temporary solution’[13] of hulks and resume transporting felons to America as of yore.[14] But a couple of conniving businessmen on either side of the Atlantic thought they had devised a way around these obstacles.

London merchant George Moore had been offered £500 by the British government to transport a ship full of prisoners out of Britain. Moore’s American contact, Maryland trader George Salmon, supplied the crucial information that, despite America’s longstanding opposition to the English ‘Empty[ing] Their Jails on them,’ this disapproval had not yet been articulated in law.[15] Legally, felons could still be imported into America.[16] To conceal their legal but frowned-upon activities, Moore officially listed the Baltimore-bound Swift’s destination as Nova Scotia, Canada and classified the convicts as ‘free indentured servants’ to be sold for profit.[17]

Just days into the Swift’s voyage, however, the convict rumour mill was in overdrive. As convict Charles Keeling later testified, the convicts on board had been told by the Swift’s sailors that,

‘it was a doubt, whether they would accept of us in America, or not, and…if they could not dispose of us in America, they were to dispose of us in Africa…They said they were to leave us where they pleased.’[18]

Not surprisingly, the Swift was still in the English Channel when the news that they might end up in Africa caused the convicts to turn mutinous. A number of them took off their own irons, rushed upon Captain Pamp’s cabin and helped themselves to firearms, seized control of the ship and freed their fellow convicts. Mayhem ensued, but Partridge and David Killpack were two of the 48 convicts who succeeded in securing one of the coveted positions on the Swift’s two longboats. Less fortunate mutineers fell into the sea and drowned in the desperate attempt to escape.[19]

Some of the escapees were never seen again, but just over half were recaptured soon after the mutiny — Partridge and Killpack were among them.

The Old Bailey Again

Partridge was ‘found at large,’ in the market town of ‘Tunbridge’[20] in Kent ‘on the 1st of September…without any lawful cause’[21] and apprehended by a man named Robert Clarke. At Partridge’s second trial at the Old Bailey on 10 September 1783, Clarke stated that, unlike others who had escaped, Partridge did not make any resistance but ‘surrendered himself very peaceably and quietly.’[22] Captain Pamp’s first mate, Thomas Bradbury, also swore that ‘[Partridge’s] behaviour was well enough’ and, as far as he knew, he had not been ‘remarkably active’ during the mutiny.[23] Partridge, himself, simply stated, ‘I leave myself to the mercy of the Court.’[24] But the Court, faced with 26 people guilty of returning from transportation from the Swift, was not inclined to be merciful that day. Despite testimony revealing him to have been a non-violent escapee, Partridge was found guilty and given a death sentence.[25]

Six of the returned transportees did hang for their part in the mutiny. However, Partridge, Killpack, and the remainder were brought before the Court again a few days after their trials and informed,

‘The King…has thought fit to extend his mercy to you…upon condition of your being…transported to…some of his Majesty’s Colonies in America for the term of your natural lives; and it is necessary, peculiarly necessary in your cases, who have endeavoured to elude, so daringly to elude the sentence of the law, to inform you, that if you are found at large within this kingdom of Great Britain, you will shut out every expectation of receiving any more his Majesty’s mercy.’[26]

Thus banished from the kingdom of Great Britain, Partridge and Killpack were held on the prison hulk Censor. By October 1784, highwayman James Wright had become one of the Censor‘s prisoners, too. The hulk was where these men worked and fought off disease until 27 February 1787, when the transport ship Scarborough began receiving prisoners bound for Kamay (Botany Bay). In addition to Partridge, Killpack, James Wright and Hugh Hughes from the Censor hulk, the Scarborough took on more than 200 other convicts, including Thomas Eccles and Edward Elliott, from the Ceres hulk. [27] With Partridge, Killpack, and other mutineers from the Swift along with some who had mutinied on the Mercury in 1784 it is hardly surprising that, once thrown together, Scarborough’s convict passengers plotted another uprising, albeit one that was swiftly uncovered and thwarted.[28]

Richard Rice: The Left-Handed Flogger

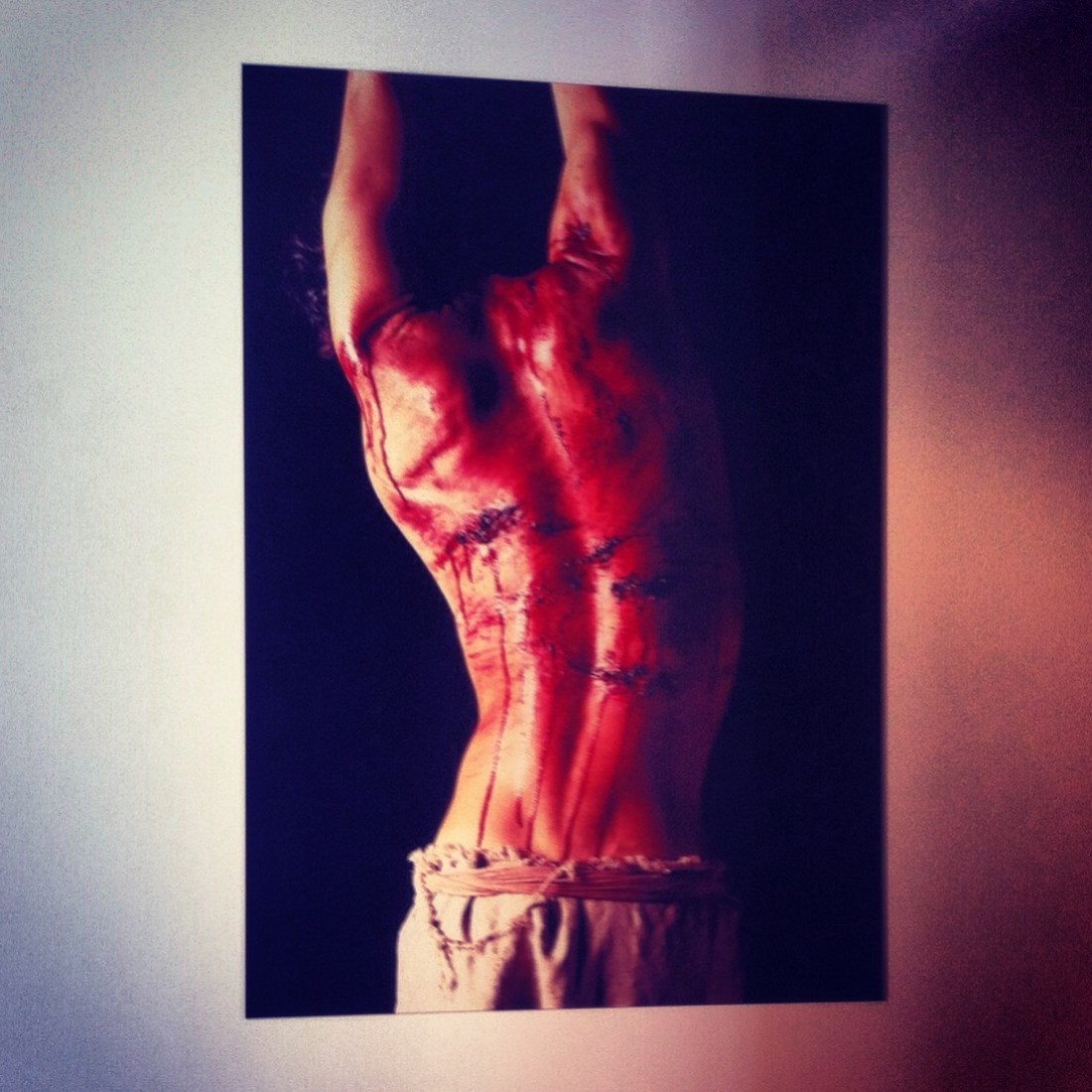

It would not have been long after the First Fleet’s arrival at Warrane (Sydney Cove) in Cadigal Country on 26 January 1788 that the local Aboriginal People gained the opportunity to witness convicts on the wrong end of a fiendish cat o’ nine tails; bound, helpless, and enduring its ‘pulping and shredding of flesh and laying bare of bone.’[29] Though the Aboriginal People in the region were no strangers to violence in their own culture, this particular brand of punishment was, for them, beyond the pale. The likes of Arabanoo, Barangaroo, and Daringa, were horrified, outraged, and driven to tears by it; indeed, on one occasion Barangaroo was even compelled to ‘seize a stick’ and ‘wallop the flogger’ to put an end to the gory spectacle.[30] For the British, though, flogging was a very typical punishment for minor offences in England and would remain so in the penal colony.[31] John Martin, for example, received 25 lashes in August 1788 merely for lighting a fire in a hut in the middle of winter.

With so many floggings being inflicted, someone obviously had to be on the other end of the lash. Less obvious, perhaps, is that the floggers were usually convicts themselves — Richard Partridge was one of them. How, when, or why exactly Partridge became a flogger is unknown, but the role might have been assigned to him as a form of punishment for some minor offence he committed in the colony. There is, however, another intriguing possibility, and it involves the man who became Australia’s first bushranger: ‘Black Caesar.’ Caesar was probably a Creole slave who escaped from America during the Revolutionary War and subsequently became one of eleven black men transported as convicts with the First Fleet. Just three months into the colonial experiment, on 30 April 1788, Black Caesar was accused of stealing four pounds of bread from none other than Richard Partridge. Caesar denied the charge and the outcome of the trial is unknown, but it is highly probable Caesar was found guilty and flogged for his crime, as an officer recorded in his journal that there had been ‘plenty of flogging’ on the day of Caesar’s trial.[32] Given that Partridge was the victim of Caesar’s crime, it is possible that Partridge was called upon to personally dish out the punishment. Perhaps this was the moment his preference or ability to use his left hand while flogging was first noted and ‘The Left-Handed Flogger’—one half of a monstrous, misery-inducing, two-headed, eighteen-tailed cat—was born.

As the following account of the flogging of Irish rebels at Toongabbie, Toogagal Country, in early October 1800 reveals, the act of flogging was performed collaboratively. The left-handed flogger Partridge, alias ‘Richard Rice,’ alternated whiplashes with the right-handed flogger William Johnston, alias ‘John Johnson,’ usually to the steady rhythm of a beating drum.[33]

‘One man, named Maurice Fitzgerald, was sentenced to receive three hundred lashes, and the method of punishment was such as to make it most effectual. The unfortunate man had his arms extended round a tree, his two wrists tied with cords, and his breast pressed closely to the tree, so that flinching from the blow was out of the question, for it was impossible for him to stir….[T]wo men were appointed to flog, namely, Richard Rice, a left-handed man, and John Johnson, the hangman from Sydney,[34] who was right-handed. They stood on each side of Fitzgerald; and I never saw two threshers in a barn move their flails with more regularity than these two man-killers did, unmoved by pity, and rather enjoying their horrid employment than otherwise. The very first blows made the blood spout out from Fitzgerald’s shoulders; and I felt so disgusted and horrified, that I turned my face away from the cruel sight….I could only compare these wretches to a pack of hounds at the death of a hare, or tigers, who torment their victims before they put them to death; and yet these fellows, I venture to assert, were arrant cowards; for cowardice is always equal to cruelty—fellows who dare not face a brave foe, but would cut a submissive captive to mince-meat.

‘I have witnessed many horrible scenes; but this was the most appalling sight I had ever seen. The day was windy, and I protest, that although I was at least fifteen yards to leeward, from the sufferers, the blood, skin, and flesh blew in my face as the executioners shook it off their cats. Fitzgerald received his whole three hundred lashes, during which Doctor Mason used to go up to him occasionally to feel his pulse, it being contrary to law to flog a man beyond fifty lashes without having a doctor present. I never shall forget this humane doctor, as he smiled and said, “Go on; this man will tire you both before he fails!”[35]

Dr. Mason’s remark is shocking in its callousness but it is also revealing; a single flogger would have tired too quickly when hundreds of lashes were to be inflicted upon an insubordinate convict. Even more gruesome, having both left- and right-handed floggers working in tandem maximised the surface area of the convict’s back destroyed by ‘the cat.’

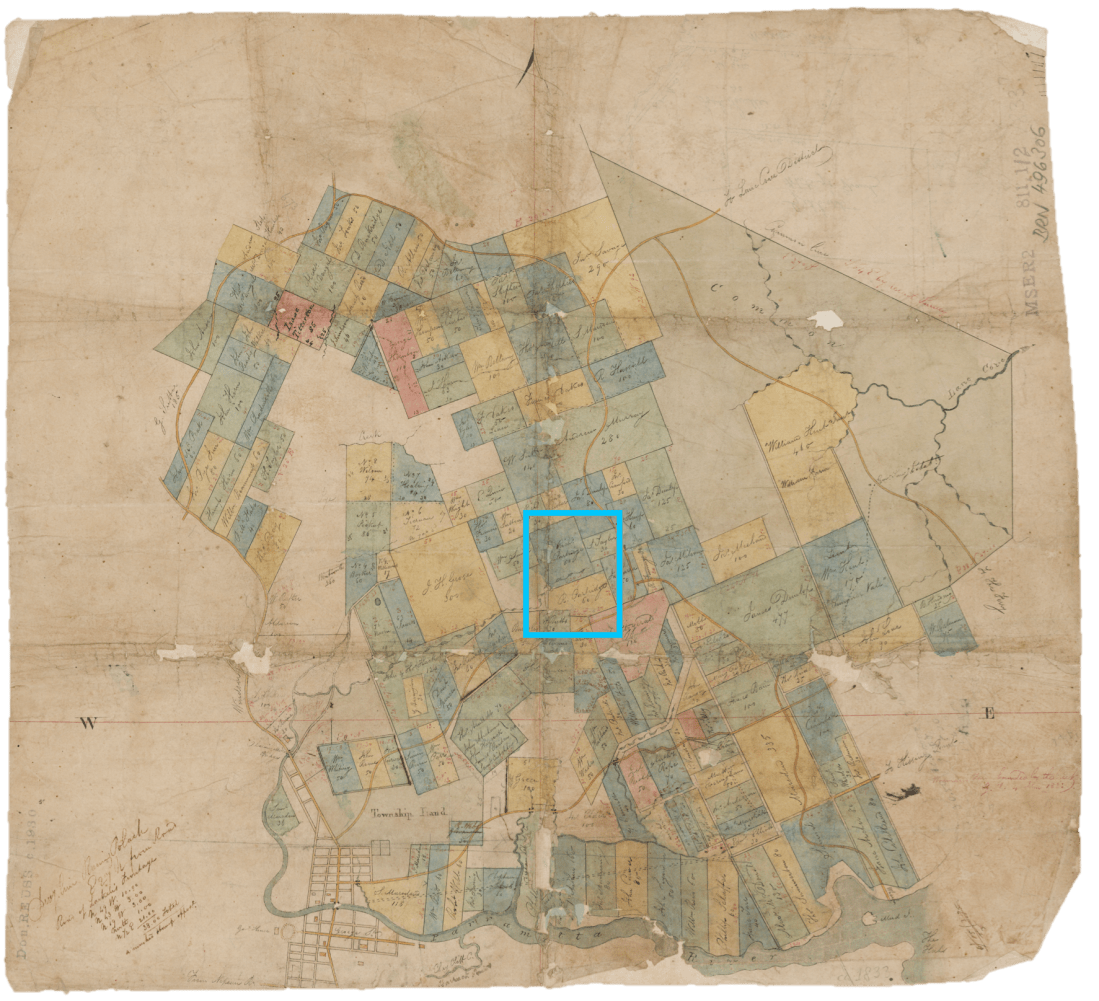

Partridge’s time as the left-handed flogger could be written off as an activity he was forced to complete as a convict under a life sentence, but the fact remains that when Partridge flogged Maurice Fitzgerald at Toongabbie in 1800 he did so not as a convict under duress but as a free colonist, for he had received his ‘Absolute Pardon’ on 12 September 1797 and a 60-acre grant in the district of the ‘Northern Boundary Farms’ (present-day Carlingford) in Bidjigal Country three days later.[36] In fact, Partridge freely chose to continue working in law enforcement as a Parramatta night watchman in 1797, then as a ‘Constable, Goaler [sic],’ poundkeeper, and ‘overseer of ironed prisoners,’ during which time he used both ‘Rice’ and ‘Partridge’ interchangeably.[37] As gaoler, he would have been responsible for the Irish rebels taken into custody following the Battle of Vinegar Hill at Mogoaillee (Castle Hill), Bidjigal Country in 1804. He also frequently provided evidence in criminal cases ranging from murder to bushranging and theft. While the harsh corporal punishment Partridge and Johnston inflicted was widely condemned decades later when Joseph Holt recalled the flogging they had given Fitzgerald, as historian Matt Allen reminds us, context is important: at the time these punishments were inflicted they were motivated by ‘a justified fear of Irish convict uprising, in a period when Britain was at war and Ireland in rebellion, … and corporal punishment was widely viewed as necessary.’[38]

The Partridge Family

Mrs. Richard Partridge had been a highwaywoman with a death sentence before her sentence was commuted to seven years transportation[39] aboard the First Fleet’s Lady Penrhyn.[40] At Warrane (Sydney Cove), Richard and Mary were involved with each other, but it is possible they had an existing connection of some sort in England, because Mary’s co-accused at the Old Bailey was a man who shared the same surname as Richard.

The couple appear to have had a child together by 1791, as ‘Mary – daughter of Richd Rice’ was recorded among the earliest burials in the parish of St. John’s, Parramatta, in November that year.[41] Two years later, on 3 November 1793 the still unwed Richard and Mary had a son named Richard.[42] Marriage was still a long way off when they welcomed the arrival of daughter Mary Ann in 1797; Richard did not make Mary his ‘lawful rib’ until 5 November 1810 when they were in their late 40s. Their belated wedding at St. John’s Church, Parramatta was witnessed by Elizabeth Cook and fellow First Fleet convict-turned-settler in the Northern Boundary district in Bidjigal Country: John Martin.[43]

In the 1790s the Partridges adopted and ‘reared…from his infancy’ a little orphan boy of the Dharug People in Parramatta, roughly the same age as Richard junior.[44] They called him ‘Daniel,’ but those who knew him typically referred to him simply as ‘Dan’ until he reached adolescence and began to be called Mow-watty or Moowattin: ‘bush path.’ Daniel Mow-watty’s story is one of a bilingual, bicultural individual who was torn between two worlds; he ultimately became the first Aboriginal person tried by a Superior Court in New South Wales as well as the first Aboriginal person (legally) executed in the colony. He was about twenty-four years old at the time of his execution in 1816—roughly the same age his adopted parents were when they received their death sentences.[45] As his adopted father, Partridge may have been there to support his son in his final moments. If so, the experience would have given the Left-Handed Flogger—who had meted out so many painful punishments to convicts over the years—yet another perspective of how brutally poetic Justice could be.

Sudden Death

In 1831, ‘Old Dick Rice’ was busy making plans for the future. He had good reason to do so; the seventy-two-year-old was ‘in perfect health’ and ‘had not known what illness was for a number of years.’[46]

Nevertheless, he had decided it was time to downsize. In mid-May, he advertised his property in Parramatta to be sold and arranged to move to his farm, which was then being maintained by his son. The former laundry thief had even accumulated a sizeable sum of money, in the vicinity of several hundred pounds, which he had secreted away in ‘an old tea-pot’ for safekeeping.[47]

Life, then, was in perfect order when Dick retired to the bed he shared with his wife Mary on Saturday 21 May 1831 and drifted off into a peaceful, eternal sleep.[48]

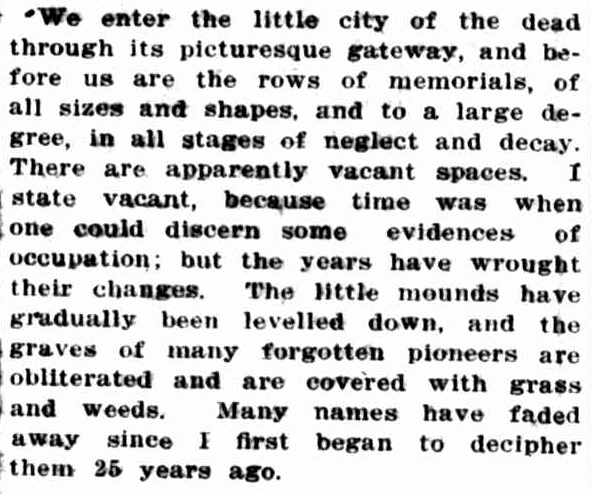

Richard Partridge was laid to rest on Monday 23 May 1831 in the parish of St. John’s, Parramatta, in Burramattagal Country. Though no trace of a headstone has survived, it seems likely he would have been buried in a marked grave, somewhere in St. John’s Cemetery, given his financial status when he passed away. Perhaps it was one of the headstones the ‘Old Parramattans’ of a later generation saw crumbling away before their eyes to their utter dismay.[49] If it ever existed at all, then, the materials used to make his headstone must have been inferior; even so, it could never be said that The Left-Handed Flogger’s tale was in any way inferior to those of other First Fleeters whose headstones endure to this day at St. John’s.

CITE THIS

Michaela Ann Cameron, “Richard Partridge: The Left-Handed Flogger,” St. John’s Online, (2016) https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/richard-partridge/, accessed [insert current date]

Further Reading

Michaela Ann Cameron, “Daniel Mow-watty: The Boy Who Strayed From The Bush Path,” St. John’s Online, (2016), https://stjohnsonline.org/further-reading/daniel-mow-watty/, accessed 30 March 2016.

References

- Emma Christopher, A Merciless Place: The Lost Story of Britain’s Convict Disaster in Africa, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers: The True History of the Meeting of the British First Fleet and the Aboriginal Australians, 1788, (Edinburgh, London, New York, Melbourne: Canongate, 2003).

- A. Roger Ekirch, “Great Britain’s Secret Convict Trade to America, 1783–1784,” American Historical Review, Vol. 89, No. 5 (Dec., 1984): 1285–1291.

- John Hirst, Freedom on the Fatal Shore: Australia’s First Colony, (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2008).

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 10 September 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830910-19), accessed 29 March 2016.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 11 May 1785, trial of GEORGE PARTRIDGE and MARY GREENWOOD (t17850511-3), accessed 29 March 2016.

- Elaine M. Sheehan, “The Identity of Richard Rice: ‘The Left Handed Flogger,’” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 70, Pt. 2, (October, 1984): 125-132.

Notes

[1] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[2] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[3] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[4] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[5] Coversluts were outer garments worn to conceal untidy clothing. coverslut. 2016. In Merriam-Webster.com, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/coverslut accessed 23 March 2016.

[6] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[7] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[8] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[9] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[10] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[11] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 30 April 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830430-27), accessed 29 March 2016.

[12] P[arliamentary[ R[egister] iv. 106 cited in Mollie Gillen, “The Botany Bay Decision, 1786: Convicts, Not Empire,” English Historical Review, Vol. 97, No. 385 (Oct., 1982): 742.

[13] The Act passed in mid-1776 was for two years. See Mollie Gillen, “The Botany Bay Decision, 1786: Convicts, Not Empire,” English Historical Review, Vol. 97, No. 385, (Oct., 1982): 742; Cassandra Pybus, Black Founders: The Unknown Story of Australia’s First Black Settlers, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2006), p. 57.

[14] A. Roger Ekirch, “Great Britain’s Secret Convict Trade to America, 1783–1784,” American Historical Review, Vol. 89, No. 5 (Dec., 1984): 1285.

[15] A. Roger Ekirch, “Great Britain’s Secret Convict Trade to America, 1783–1784,” American Historical Review, Vol. 89, No. 5 (Dec., 1984): 1289.

[16] In fact, it would be another five years before this became law across the United States of America.

[17] Emma Christopher, A Merciless Place: The Lost Story of Britain’s Convict Disaster in Africa, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 255–7. On arrival in Baltimore, they claimed that ‘a shortage of provisions had prevented sailing to Nova Scotia.’ James Cheston to William Randolph, February 23, 1784, CGP cited in A. Roger Ekirch, “Great Britain’s Secret Convict Trade to America, 1783–1784,” American Historical Review, Vol. 89, No. 5 (Dec., 1984): 1288.

[18] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 10 September 1783, trial of CHARLES KEELING (t17830910-20), accessed 26 March 2016; Emma Christopher, A Merciless Place: The Lost Story of Britain’s Convict Disaster in Africa, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 256–7.

[19] Don Jordan and Michael Walsh, White Cargo: The Forgotten History of Britain’s White Slaves in America, (Washington Square, N.Y.: New York University Press, 2008), p. 277.

[20] Modern-day spelling is Tonbridge, even though the pronunciation is still Tunbridge.

[21] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 10 September 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830910-19), accessed 29 March 2016.

[22] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 10 September 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830910-19), accessed 29 March 2016.

[23] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 10 September 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830910-19), accessed 29 March 2016.

[24] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 10 September 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830910-19), accessed 29 March 2016.

[25] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 10 September 1783, trial of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (t17830910-19), accessed 29 March 2016.

[26] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 10 September 1783, punishment summary of RICHARD PARTRIDGE (s17830910-1), accessed 29 March 2016

[27] Elaine M. Sheehan, “The Identity of Richard Rice: ‘The Left Handed Flogger,’” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 70, Pt. 2, (October, 1984): 126; Home Office, Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania; (The National Archives Microfilm Publication HO10, Pieces 1–4, 6–18, 28–30); The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England.

[28] Michaela Ann Cameron, “Scarborough,” Dictionary of Sydney, (2015) http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/scarborough, accessed 29 March 2016.

[29] Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers: The True History of the Meeting of the British First Fleet and the Aboriginal Australians, 1788, (Edinburgh, London, New York, Melbourne: Canongate, 2003), p. 190. For St. John’s Online’s dual naming policy, see Michaela Ann Cameron, “Name-Calling: A Dual Naming Policy,” in St. John’s Online, (2020), https://stjohnsonline.org/editorial-policies/name-calling-a-dual-naming-policy/, accessed 13 April 2020. The essay discusses giving prime position to indigenous endonyms and subordinating European imposed exonyms in both the colonial Australian and colonial American contexts and was adapted from “Name-Calling: Notes on Terminology,” in Michaela Ann Cameron, (Ph.D. Diss.), “Stealing the Turtle’s Voice: A Dual History of Western and Algonquian-Iroquoian Soundways from Creation to Re-creation,” (Sydney: Department of History, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sydney, 2018), pp. 25–35, http://bit.ly/stealingturtle, accessed 25 August 2019.

[30] Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers: The True History of the Meeting of the British First Fleet and the Aboriginal Australians, 1788, (Edinburgh, London, New York, Melbourne: Canongate, 2003), p. 189.

[31] John Hirst, Freedom on the Fatal Shore: Australia’s First Colony, (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2008), pp. 50–61.

[32] Cassandra Pybus, Black Founders: The Unknown Story of Australia’s First Black Settlers, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2006), p. 96.

[33] Cassandra Pybus, Black Founders: The Unknown Story of Australia’s First Black Settlers, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2006), p. 96.

[34] A number of secondary sources state that Richard Partridge alias Rice was ‘the notorious hangman from Sydney,’ but the claim seems to have been a misreading of this primary source, which clearly identifies both Rice and Johnson as floggers and Johnson specifically, as ‘the hangman from Sydney.’ Elaine M. Sheehan’s article only refers to Johnson as the public executioner: see Elaine M. Sheehan, “The Identity of Richard Rice: ‘The Left Handed Flogger,’” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 70, Pt. 2, (October, 1984): 126–7. The secondary sources that state Partridge was ‘the colony’s notorious hangman’ include: Keith Vincent Smith, “Moowattin, Daniel (1791-1816),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/moowattin-daniel-13107/text23713, published first in hardcopy 2005, accessed 29 March 2016; Lisa Ford and Brent Salter, “From Pluralism to Territorial Sovereignty: The 1816 Trial of Mow-watty in the Superior Court of New South Wales,” Indigenous Law Journal, Vol.7, Issue 1 (2008): 68. However, I have recently discovered a primary source dated 1834, within the lifetime of Richard Partridge alias Rice, specifically an 1834 transcription of a St. John’s Cemetery headstone epitaph that states Simon Taylor was hanged by ‘Rice the Gaoler.’ See Michaela Ann Cameron, ‘I Am But Sleeping Here,’ St. John’s Online (2020) for the evidence and a fuller discussion as well as Michaela Ann Cameron, ‘St. John’s Taphophiles,’ St. John’s Online (2022).

[35] Joseph Holt, Memoirs of Joseph Holt, General of the Irish Rebels, in 1798, In Two Volumes, Vol. II, (London: Henry Colburn, Publisher, 1838), pp. 118–122, accessed 28 March 2016.

[36] New South Wales Government, Special Bundles, 1794–1825, Series 898, Reels 6020–6040, 6070; Fiche 3260–3312, State Records Authority of New South Wales. Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia.

[37] Governor Hunter, AONSW, Reel 773, Pardons, Conditional and Absolute, c.1791–1841, p. 25 cited in Elaine M. Sheehan, “The Identity of Richard Rice: ‘The Left Handed Flogger,’” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 70, Pt. 2, (October, 1984): 127.

[38] From 1815, he was paid out of the Police Fund for working as a ‘carter’; that is, transporting bricks intended for Government buildings in Parramatta and provisions to work parties working on projects including the Western Road. Matthew Allen, “Samuel Marsden: A Contested Life,” St. John’s Online, (2020), https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/samuel-marsden, accessed 27 March 2020. Mogoaillee, the Aboriginal endonym for ‘Castle Hill’ was recorded by Reverend William Branwhite Clarke in his diary entry dated 6 November 1840, W. B. Clarke – Papers and Notebooks, 1827–1951, MLMSS 139 / 7, Item 5, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, cited in The Hills Shire Council, Traditional Aboriginal Names for the Natural Regions and Features in the Hills Shire, (The Hills, NSW: The Hills Shire Council, Local Studies Information, c. 2009), p. 1, https://www.thehills.nsw.gov.au/files/sharedassets/public/ecm-website-documents/page-documents/library/library-e-resources/traditional_aboriginal_names_baulkham_hills_shire.pdf, accessed 10 April 2020. Mogoaillee comes from mogo, stone hatchet, while aillee may be possessive, meaning belonging to somewhere or something, for example, place of stone for hatchets.

[39] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2), 11 May 1785, trial of GEORGE PARTRIDGE and MARY GREENWOOD (t17850511-3), accessed 29 March 2016.

[40] Home Office, Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania; (The National Archives Microfilm Publication HO10, Pieces 5, 19–20, 32–51); The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England.

[41] No record of Mary Rice / Partridge’s birth has been located at the time of this biography’s publication. Her burial took place on 27 November 1791; Parish Burial Registers, Textual records, St. John’s Anglican Church Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia.

[42] Significantly, despite the fact that he was typically called Richard Partridge Jnr, he, too, was known to use the alias ‘Rice’ even in adulthood. See Elaine M. Sheehan, “The Identity of Richard Rice: ‘The Left Handed Flogger,’” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 70, Pt. 2, (October, 1984): 128. Richard Jnr was baptised on 10 February 1794 at St. John’s Church, Parramatta; Parish Baptism Registers, Textual records, St. John’s Anglican Church Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia.

[43] Parish Marriage Registers, Textual records, St. John’s Anglican Church Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia. Richard and Mary’s daughter, Mary Ann Partridge (1797–1877), died when she was an old woman under tragic circumstances. Her clothing caught fire and she ran out of the house alight, tripped and fatally hit her head. When she was discovered by her eight-year-old granddaughter, her body was charred and her dogs had eaten her face. “Frightful Death By Burning Near Sydney,” Weekly Times (Melbourne, VIC: 1869-1954), Saturday 11 August 1877, p. 15.

[44] “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803-1842), Saturday 28 September 1816, p. 2.

[45] The execution took place on Friday 1 November 1816; “Sydney,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803-1842), Saturday 2 November 1816, p. 2; Lachlan Macquarie, Lachlan Macquarie’s Journal, Friday 1 November 1816, accessed 26 March 2016.

[46] “Sudden Death,” Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828-1838), Saturday 28 May 1831, p. 2.

[47] “Sudden Death,” Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828-1838), Saturday 28 May 1831, p. 2.

[48] “Sudden Death,” Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828-1838), Saturday 28 May 1831, p. 2. He was buried at St. John’s Cemetery, Parramatta on Monday 23 May 1831, the day after his lifeless body was discovered by his wife. The burial was officiated by Reverend Samuel Marsden. Parish Burial Registers, Textual records, St. John’s Anglican Church Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia.

[49] William Freame, “Among the Tombs: St. John’s Cemetery,” Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate (Parramatta NSW: 1888-1950), Monday 19 October 1931, p. 4.

© Copyright 2016 Michaela Ann Cameron