and

The Story of St. John’s First Burial

Supported by a Create NSW Arts and Cultural Grant – Old Parramattans, St. John’s First Fleeters, & Rogues

Beginnings

Even a burial ground, where so many stories ended, has many beginnings. The story of St. John’s Cemetery, Parramatta begins among knee-high native grass on ‘a gently sloping hill’ in the life-sustaining hunting grounds of the Burramattagal clan of the Dharug People.[1] It also begins with newcomers enclosing that once open space to preserve their cattle from wandering. Yet the story of this cemetery just as surely begins with its first burial; a tale for which three saints of London, St. John, St. James, and St. Giles, shall serve as our guides. The three saints will lead us to a plantation in the American colonies, a royal palace, and even among the ‘swarm[s]’ of ‘strumpets’—the ‘notoriously lascivious and profligate’ ‘ladies of the pavement’—on ‘Lewkner’s Lane.’[2]

St. John

The first saint leads us to the broad part of the ancient thoroughfare bearing his name: St. John Street, Clerkenwell. Cars pass by, but the accompanying modern sights, sounds and smells begin to slowly fade. Where there was once a humble bicycle rack on the island in the centre of the road there is now the ‘ruinous’ Hicks’s Hall standing—albeit rather uncertainly—on that same spot in 1773.[3] If the Hall’s ‘bulging walls’ could talk, the once ‘very stately’ Sessions House for the County of Middlesex would no doubt boastfully tell of the trials of King Charles I’s twenty-nine Regicides that commenced there in 1660 and other historic trials it had hosted.[4] But on this September day in 1773 within the Hall’s ‘decrepit’ edifice of ‘decaying brick and rotten woodwork,’ there is a mere boy, probably no more than eleven years old, awaiting news of his fate at the General Quarter Sessions of the Peace — he is the one St. John wants us to see.[5] The lad, recorded as ‘Christopher McGee,’ is found guilty of ‘Petit Larceny’ with several other miscreants and ‘Ordered and Directed to be Transported as soon as conveniently might be to some of his Majesty’s Colonies and Plantations in America for the Term of Seven Years.’[6]

For the 50,000 or so ‘surplus’ British men and women and, of those, the 18,600 Londoners specifically who had been dealt this hand since the passing of the Transportation Act in 1718, a sentence of transportation more often than not meant one thing: forced labour on a plantation in the Chesapeake where tobacco was king.[7] Thus, when the convenient time for his expulsion from Great Britain arrived, Christopher was fitted with a collar and padlock around his neck, chained to a board and to five other felons in a prison hold, probably ‘not above sixteen feet long’ yet crowded with as many as 150 other convicts if not more, below deck on a Maryland- or Virginia-bound ship.[8] There he remained for the eight- to ten-week transatlantic voyage, thrown about relentlessly by the sea with his iron chains rubbing his skin raw, inhaling body odour ripe beyond imagination as well as excrement and vomit, in constant close proximity to gaol-born diseases or even suffering from one himself, and witnessing fellow cons die around him. What little food was available to him was stale, rotten and putrid, especially in the second half of the journey. They were conditions that would have weakened the strongest and the healthiest let alone felons who had typically lived poverty-stricken, undernourished lives and had already spent considerable time exposed to diseases in filthy urban slums and prisons. But from these enervating, dreadful conditions on board the ship, Magee and the other convicts were expected to somehow emerge and subject their bodies to the exertions of agricultural labour in a foreign climate.[9]

Debilitated and pathetic as Magee and the other transported convicts undoubtedly were, there were those in the Chesapeake who were more than willing to pay for such labourers—and the profit-hungry merchants knew it.[10] Planters needed a cheap labour force to carry out the approximately 36 steps required for the tobacco crop’s cultivation and also to perform other skilled jobs on their large, self-contained plantations, so they had no qualms about purchasing convicts.[11] They were already using the permanently unfree African and African American slaves as well as indentured servants from Britain’s underclass who, unlike the convicts, had voluntarily sold themselves into temporary servitude in the hopes the ‘freedom dues’ they were contractually awarded on completing their term of service would set them up in a new life and break the cycle of poverty. By Magee’s time, convicts had no such entitlements at the close of their sentences and they were much cheaper than African slaves, too, making them a bargain indeed. A robust, adult male African slave, for example, could fetch as much as fifty pounds at auction, whereas an adult male convict usually sold for between ten and fourteen pounds.[12] While there were undoubtedly serious problems with getting British convicts to accept that they were now the property of fellow Englishmen when such arrangements did not occur on their native isle, the convicts shared a common language and culture with their masters.[13] This was in direct contrast to the considerable linguistic and cultural barriers between masters and newly arrived African slaves as well as between the African slaves themselves who had been sourced from different parts of the continent and had mutually unintelligible languages and customs.

On arrival in the colony the upcoming convict auction was advertised in newspapers, and the merchants—needing to cover the cost of transporting the convicts and eager to earn a profit on the sale of each con besides—ordered their human cargo to spruce themselves up with the aid of some water, a comb, and sometimes with the addition of a cap or a wig.[14] A bowl of rum-spiked punch was readied to refresh prospective buyers and Christopher Magee and his fellow cons were lined up above deck ‘like so many Oxen or Cows.’[15] Planters with their pockets full of money did their best to ignore the ‘peculiar smell incident to all servants just coming from the ships’ whilst peering into the convicts’ mouths to examine their teeth, squeezing their muscles like they would a horse, and grilling the convicts about their convictions to gauge whether they would be more trouble than they were worth.[16] One by one, each was sold to the highest bidder. As a pre-pubescent male, Magee was likely sold at a low price. Perhaps he was purchased by a young or low level planter who lacked the funds for slaves or adult male convicts or by a more well-heeled planter who was happy to augment his labour force with whatever was available.[17] Whoever Magee’s master was, he probably recognised the merits of buying the youngster. It was a long-term investment that would take a city-dwelling petty thief bred to nothing but pickpocketing at an age when he still could be bred to something worthwhile. By spending his formative years on a plantation in the Chesapeake, Magee worked in the fields alongside African and African American slaves as well as British indentured servants and was, in all probability, the recipient of corporal punishment at the hands of his ‘owner’ not to mention a traumatised witness to much more brutality inflicted on the slaves. But in this harsh place Magee was also ‘bred to husbandry.’[18]

How or why Magee returned to the streets of London at the end of his sentence, despite the utility of his agricultural skills in the American colonies, is unknown. Generally speaking, though, since convicts were not owed ‘freedom dues’ upon completing their period of servitude he would not have received land, equipment, or money to get him started. By the time Magee had served his sentence, land in the Chesapeake was increasingly scarce and it is doubtful he could have raised the funds even if land had been available. A convict had little chance of saving money from their own additional labour in preparation for life after emancipation since anything they produced during their servitude was automatically the property of their owner and liable to confiscation.[19] There was also the rather large matter of the American Revolutionary War, which began around a year after Magee’s arrival and saw the colonists fight for and declare their independence from Great Britain. While convict transportation was not cited as a specific catalyst for that great schism, the English had long used the colonies as ‘a sinke to drayen England of her filth and scum [sic]’ and, if Benjamin Franklin’s reference to British convicts as ‘Human Serpents sent us by our Mother Country’ in the lead up to the Revolution was anything to go by, convict transportation was yet another gripe the Americans had with their ‘tyrannical’ mother; it was further proof the British thought of and treated their colonial subjects as inferiors.[20] Ironically, the brand new, liberty-loving United States of America was, therefore, especially inhospitable to a newly freed British convict. Weighing all this up, Magee likely concluded he might as well be a vagrant in London as in the Chesapeake. The exceptional state of affairs brought about by the Revolutionary War may have also presented Magee with opportunities not usually available to British convicts. He would have witnessed the war firsthand and, while it still raged, might have even been recruited into the Loyalist cause to fight alongside the British troops against the rebellious colonists—especially if there was something in it for him, such as early emancipation or free passage back across the Atlantic.[21] If so, his input did not help the British win the war but it would certainly explain how Magee eventually managed to make that return trip, which was usually prohibitively costly for a convict.

Whatever the reason, the timing, or the means, we know Magee made it back to London after eight years in America—and that made him quite a rarity. Far more typical was the former convict’s speedy resumption of his criminal activities once he was back in his familiar surroundings and reunited with his kith and kin. He was probably the ‘Christopher Magee’ tried and convicted of felony at the General Quarter Session of the Peace held at Guildhall, Middlesex as early as 13 October 1781 and incarcerated at the Tothill Fields Bridewell two days later.[22] If so, it was not enough to swear him off lawbreaking for good.

St. James

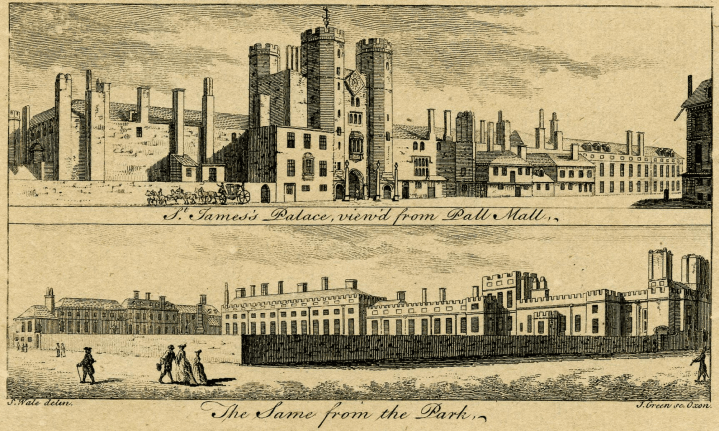

The second saint now beckons us into a lavish room at St. James’s Palace, Westminster, London and into the presence of the Honourable Miss Ann Boscawen—none other than Queen Charlotte’s Maid of Honour. Little did Miss Boscawen know on that Saturday evening in July 1784, a ‘large leather portmanteau,’ which ought to have been wending its way to her through London’s streets, was instead having an adventure that was decidedly unworthy of her honoured name, all thanks to the former convict Christopher Magee.[23]

We could be forgiven for thinking Magee was a thief who longed to be caught. For ‘about six in the evening’ he had followed the cart carrying Miss Boscawen’s portmanteau through the busy Fleet-market, giving local people-watchers plenty of opportunity to observe him making numerous grabs at the leather bag in London’s summer twilight.[24] Nor had there been anything inconspicuous about Christopher’s behaviour when he fled with his prize on his shoulders and almost ran over the child of shop owner John Hayes, who promptly followed the suspicious Magee to the nearby Artichoke Alehouse. With little difficulty, therefore, Hayes had soon led the carman to both the thief and the bag, which was by then deposited under a seat in the Artichoke’s tap-room.

Nevertheless, the seemingly reckless Magee proved to have a touch of the artful dodger about him after all. At his trial at the Old Bailey four days later, for instance, he used an alias, ‘Charles Williams,’ most likely to hide his prior convictions. And by claiming, ‘A gentleman asked me to carry this portmanteau for him into Smithfield, to the Ram, and he would give me sixpence,’ Magee also managed to openly admit to the undeniable—that he had transported the Honourable Miss Boscawen’s bag and placed it under the seat—whilst distancing himself from the deliberate act of robbery itself. [25] Such arguments were often used by captured crims; all positive identifications of the accused by numerous, fine, upstanding witnesses could thus be rendered worthless if the accused convinced the court he had merely taken an opportunity to earn money by performing a simple delivery task for a seemingly trustworthy ‘gentleman’ and unknowingly participated in something untoward. Even the brazen nature of the act only reinforced the argument that the accused had been oblivious they were doing anything remotely criminal. Far from shortsighted and foolish, open theft could therefore be a safeguard against conviction for the thief in the event they found themselves before the court. The efficacy of this defence, however, all depended on how the accused was perceived, which was often also contingent on the willingness of people of good character to vouch for the defendant. Magee had no such endorsements, but there was probably also ‘something spurious in the cut of his jib’ that made the court unwilling to accept his version of events.[26] Maybe the years of servitude in the American colonies had etched upon the twenty-two-year-old Magee’s face that telltale look of hard and less-than-honest living.

Now Magee was ‘well-known…at Hick’s Hall [sic]’ and ‘the Old Bailey’ like the semi-fictional Moll Flanders, for the second time in his young life he became one of ‘His Majesty’s Seven-Year Passengers.’[27] While his punishment of seven years transportation was the same, however, he undoubtedly knew better than anyone that his destination this time would not be a plantation in ‘the land of the free.’ His eleven-year-old self had been among the last British convicts sent to the pre-Revolutionary American colonies under sentence of transportation; his twenty-two-year-old self would be among the very first British convicts sent to an altogether new colony in a far more remote and untried location.

As for the portmanteau, it no doubt made it to the palace, albeit a trifle later than expected. And by the time Magee was well established in his new surrounds beyond the seas, the Honourable Miss Boscawen, who had already served twenty years as Queen Charlotte’s Maid of Honour, was promoted to the Queen’s Sempstress and Laundress.[28] She would live out her sheltered life in the Queen’s family for three decades hence, until death came to St. James’s Palace to claim her at the age of 87.[29]

As for us, we will not follow Christopher Magee beyond the seas just yet. A third saint insists we tarry in the eighteenth-century London metropolis a while longer. He spirits us to his namesake: the ‘extra-mural’ parish that sprung up in the sixteenth century ‘in the fields’ beyond the medieval walled city and was, by the Georgian era, the centre of Irish London.[30]

St. Giles

As she reached the top of Long Acre on foot, the midwife Ann Evers nervously asked her guide ‘little Jenny’ how much further they had to go. ‘Only a little,’ the girl replied. She knew Jenny well; they had once been neighbours for two years, but the other two young women, Eleanor McCabe and Mary Wright, were ‘strangers to [her].’[31] There was more troubling Mrs. Evers than the mere presence of those two strange women, though. It was around eight o’clock on a dark midwinter night and the midwife was well aware she was being led deep into the ‘great maze’ of close courts and gloomy, narrow, crooked, rat-infested, garbage-filled alleyways ‘crossing in labyrinthine convolutions’ where the multitudes of desperately poor Irish Catholic immigrants had taken up residence: the Rookery of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, also known as ‘Little Dublin.’[32]

Sure enough, the women turned into the ill-famed ‘Lewkner’s-lane’ and onwards to its lower end.[33] However, even as they descended into one of the tiny, damp, sub-divided cellar rooms in which the poor of these parts typically lived, crammed in ‘all higley pigley,’ the midwife Evers continued to brush aside any concerns about her own personal safety and thought of the expectant mother she had been called to help.[34] It was not long before Mrs. Evers discovered that Mary Lilly, the young woman on the bed who complained of being ‘full of pain all over,’ was ‘neither in labour nor with child.’[35]

Two days later, the midwife Evers would enter the sorry excuse for a dwelling again—this time accompanied by a constable—for the purpose of identifying the women she had interacted with that night in lamplight and shadows. But, as she looked into the faces of the women through her now ‘sadly beat,’ swollen, blackened eyes, ‘[she] could not discern a thing.’[36] Her memory of what had happened to her in that dingy room, by contrast, was all too clear. Minutes after declaring the labour a hoax, Mrs. Evers had found herself flat on her back in a dark corner of the room—the result of a violent blow to the face delivered by Mary Wright, one of the strange women who had collected her. Wright, little Jenny, and McCabe had then fallen upon her. The midwife cried out ‘murder!’ but they had stopped her mouth with their hands, throttled her, and ‘beat [her] in such a manner…[she] could not see.’[37] The frenzied attack continued with the assailants pulling the midwife’s shoes off, taking her silver buckles out, putting their hands ‘into [her] bosom and up [her] petticoats and sh[aking] her’ to discover any concealed money.[38] They also untied her top petticoat to see if she had any other pocket and were rewarded with a guinea. Then they fleeced Mrs. Evers of a pair of gold earrings and ‘an half crown.’[39] Still, Mrs. Evers’s ordeal was not yet over:

I scrambled up off the floor as well as I could…one of them laid hold of me by one arm and little Jenny by the other; they pulled off my two gold rings, they were very hard to get off; Jenny swore a sad oath and said, if they could not get it off they would cut my finger off. She got one off and put on her finger; then they pulled the other off and made a scramble for that, but I do not know who got it; then they all three ran out…[A] man and a boy came in and pushed me out.[40]

The shoeless, battered, ‘almost blind’ midwife returned to her horrified daughter Henrietta that night, ‘almost murdered.’[41]

Eleanor McCabe, Mary Wright and Mary Lilly were acquitted at the Old Bailey on 22 February 1781, largely because the physical and psychological trauma the midwife sustained in the attack rendered her incapable of positively identifying, beyond any reasonable doubt, women she openly admitted she did not know and could not see.[42] But the Middlesex Jurymen got it wrong. It was Eleanor McCabe’s room in which the dastardly deeds were done. And, according to the testimony of one Catherine Hobday of Newtoner’s-lane, St. Giles who had declined McCabe’s invitation to participate in the crime, it had all been Eleanor McCabe’s idea.[43] Furthermore, McCabe and Wright had been the sole beneficiaries of the proceeds, for Catherine stated under oath that little Jenny complained to her the day after ‘she had received no part of the Money or the Rings.’[44] All the same, little Jenny alone was well known to the victim, so little Jenny alone hanged for the crime.[45] Just before the hangman did his work at Tyburn, little Jenny ‘confessed that the Scheme for which she suffered, was not the first of the Kind wherein she was concerned; that it was a common Practice with her, and her Companions, to take Persons into their Apartments, under various Pretences, and rob them.’[46]

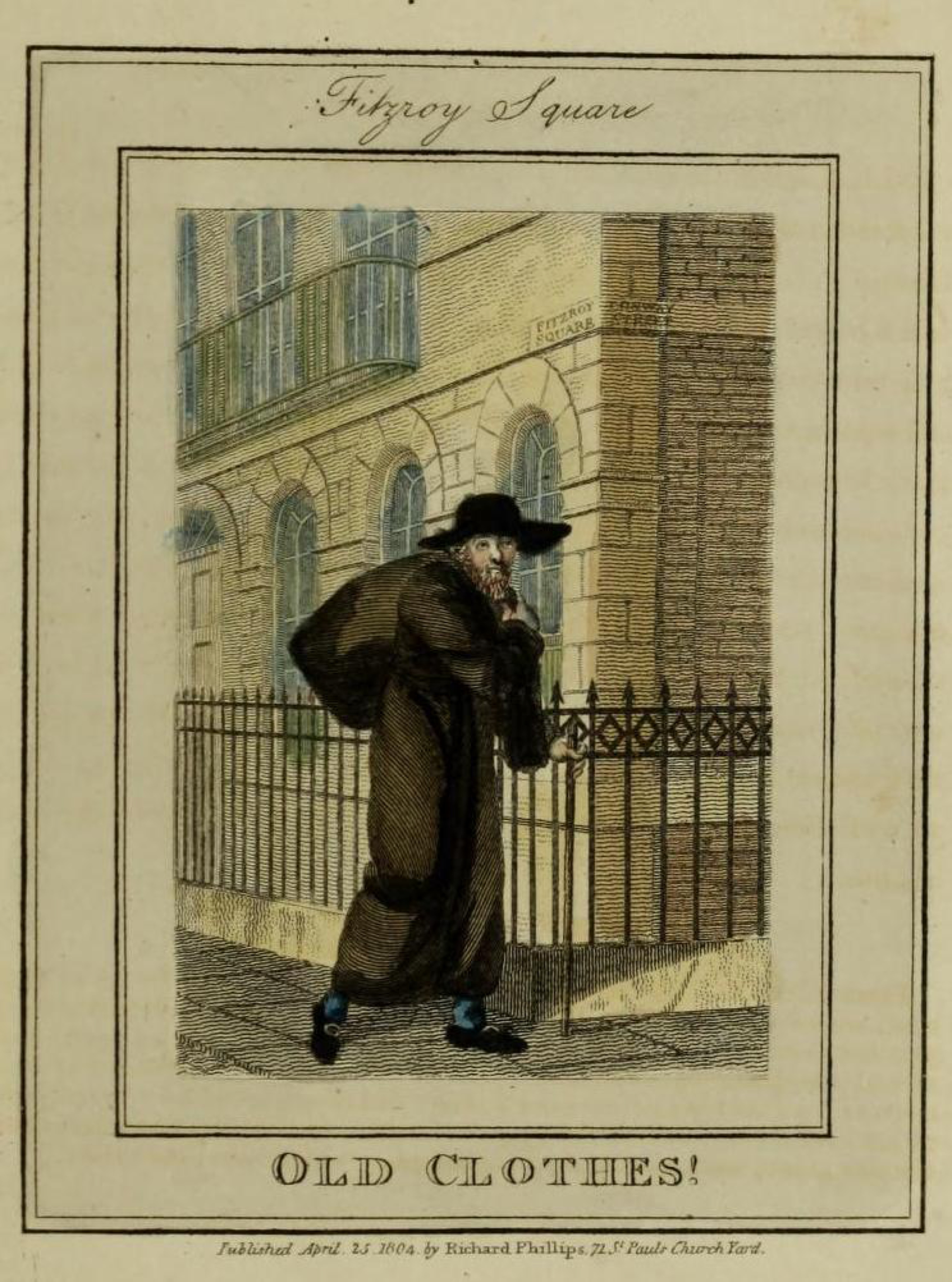

For all her failings in life, Jane ‘little Jenny’ Vincent had not sullied her last words with deceit: Eleanor McCabe and company were indeed ‘specialists.’ Less than a year earlier Eleanor had been tried at the Old Bailey on 10 May 1780 for a similar offence against Jewish ‘Old Clothes-Man’ Nathan Showell.[47] That particular crime had also featured an all-female gang of four luring an unsuspecting working person into a closed room under false pretences, in this instance selling him an old coat. Once inside, the victim could be locked in, robbed and, if necessary, violently set upon in privacy—all the better to plead innocence and mistaken identity when accused in a court of law. Eleanor’s Amazonian troop on that occasion were all aged between fourteen and seventeen years of age, including one named ‘Charlotte McCabe / McCave,’ who was more than likely Eleanor’s sibling. The Middlesex Jury found all four girls guilty of stealing eight guineas from the Old Clothes-Man and sentenced them to whipping and imprisonment for six months in the Clerkenwell Bridewell.[48] Rather conveniently for Eleanor and her accomplices, the prison was damaged during the Gordon Riots so the girls were released on 6 June 1780 having served less than a month of their six-month sentences.[49]

After also getting away with nearly murdering the midwife Ann Evers the following year, therefore, it is hardly surprising Eleanor went on a crime spree. Over a five-year period she committed a string of violent robberies in the laneways surrounding Drury-lane, St. Giles. Eleanor’s modus operandi never changed. Her crimes were always committed with at least one other female collaborator, but more ‘lovely ladies’ were usually waiting nearby in the dark to serve as reinforcements if required, whether they were captured and formally charged or not.[50]

Curtain maker John Mathews was easy prey. He wandered in the vicinity of Drury-lane at around one o’clock in the morning on 9 August 1781. Eleanor and her sidekick Mary Bowen were waiting there in the dark for the likes of him, probably half-dressed and stuck up in a corner with pipes in their mouths, ‘quaffing away, as the only antidote against care, rags, and wretchedness.’[51] Mathews’s reasons for being in such a place, where ‘every step…presented to…view some odd figure or other’ and ‘theft, whoredom, homicide and blasphemy were legible in every face’ at an hour in which ‘you may see and hear all that can shock the sight or offend the ear’ were, of course, far from innocent, so the girls did not need to work overly hard to ‘persuade’ him to enter a nearby lodging room with them on Lewkner’s-lane.[52] Once inside, the dresser of windows undressed himself, hopped into bed, and was immediately joined by both women. ‘Mary Bowen got out of bed under pretence of putting the candle out’ and ‘seize[d] hold of his Cloaths [sic].’[53] Following a struggle between Mathews and Bowen, Eleanor McCabe ‘seized hold of his Breeches and stole a Silver Watch from the Fob…of the Value of Three Guineas…and both the said women ran away.’[54] It was an all-female twist on the classic manoeuvre ‘Buttock and Twang,’ otherwise known as ‘Whore and Bully.’[55]

Eight months later, in April 1782, Eleanor and an accomplice named Ann Sherlock were indicted for assaulting Jane, the wife of John Hinty, ‘upon the highway, and taking from her person one cotton handkerchief…a check apron…a tick-in pocket…two half crowns…and five shillings in money.’[56] Again, the two accused were acquitted of a crime there is every reason to believe they were guilty of, this time because the prosecution mysteriously and most conveniently failed to appear.[57]

Eleanor was not so lucky when she alone stood before the Judge and Jury at the Old Bailey again on 11 September 1782 charged with stealing money from the ‘Tatoe Man’ William Austin. Like the curtain maker before him, the potato hawker had been walking the seedy streets around Drury-lane at a late hour.

‘That is not a very reputable neighbourhood, is it?’ the Court later asked the Tatoe man.

‘No Sir, I believe not…I goes out with tatoes round there, [Eleanor McCabe] and another person asked me for something to drink…they said I had better not go to a public house for fear I should lose my money, I went to their room.’

Court: ‘Was you sober?’

Tatoe man: ‘It was a remarkable wet day, I had drank a little drop.’

Court: ‘Pray what do you call a little drop?’

Tatoe man: ‘I had drank some gin with these women but I was sensible; when I got in I…pulled my pouch out…[Eleanor McCabe] snatched [it] and run away with it, there was fifteen shillings in it.’[58]

Eleanor claimed Austin had actually asked her to live with him and freely gifted her his hard-earned money. Unpersuaded, the Court found her guilty and sentenced her to six months in the Clerkenwell Bridewell.[59] What the Old Bailey trial record did not disclose was that Eleanor was six months pregnant at the time. The following month, the expectant mother would be treated for a sore breast by the Clerkenwell Apothecary Thomas Gibbes and on 14 December 1782 the Governor of the Bridewell, James Crozier, paid a midwife five shillings for the delivery of Eleanor’s baby.[60] As she suffered through the pain of childbirth in prison and was aided and comforted by the midwife, one wonders if Eleanor spared a thought for the innocent midwife she had brutally assaulted almost two years earlier. What became of the child is unknown but, if it lived, motherhood certainly did nothing to soften Eleanor.

Assuming the babe survived, it would have been just shy of its first birthday when Eleanor stood before the Judge and Jury at the Old Bailey yet again in December 1783. Right beside her was her old partner in crime Ann Sherlock. The pair were accused of ‘feloniously assaulting Rossiter Linton,’ a weaver they had picked up one night in Drury-lane and brought back to a bedroom on Cross-lane after Linton had ‘agreed to lay with [Sherlock] for one shilling.’[61] Linton had been in the act of undressing when Sherlock called McCabe up, threw Linton on the bed and laid over him while McCabe took off with his breeches downstairs, digging his watch and money out of them as she went. Sherlock ‘swore she would take [Rossiter Linton’s] life away if [he] made any resistance,’ which Linton would later attest in court he dared not do, not only because of this threat but also because—as was McCabe’s style—‘there were more of them at the door.’[62] Just as it was with the Jewish Old Clothes-Man, Linton was locked in. And just as it was with the midwife Mrs. Evers, Linton’s shoes were removed so that every bit of his person was thoroughly searched for concealed valuables. The entire episode lasted only ‘quarter of an hour from first to last’ and McCabe and Sherlock were taken into custody an hour later. The watch was only found upon them the next day. Eleanor rather optimistically tried her old story of the innocent bystander ‘taken up’ by mistake as the guilty party. The Court, however, were having none of it. As the trial inched towards a final verdict over a number of days the Judge made the following solemn address to the Jury:

Gentlemen of the Jury, this is a very serious story, because the prisoners stand charged with a capital offence…it is not often indeed that we meet with robberies of this kind committed under circumstances of violence on the person; but when we do meet with cases of this sort, they certainly deserve punishment; though women of this bad character must of necessity be in such a country as this, yet they ought to confine themselves to their trade, bad as it is; and in this case undoubtedly they have committed a plain robbery on this man, and if you are satisfied as to the evidence you are bound to find them guilty.[63]

The Court did so and the women were accordingly sentenced to death.[64] Yet in spite of the Judge’s assertion to the Jury that there was nothing in the case to warrant a reduction in their punishment, both women received a conditional pardon one month later and were instead ‘confined to hard labour’ in Clerkenwell Bridewell for twelve months.[65] No explanatory note was provided in the associated trial documents, but at this time the prisons and hulks were immensely overcrowded as the American Revolutionary War had left England with no place to send their prisoners under sentence of transportation. Perhaps this fact and even a lack of sympathy for victims of crimes committed by women of noted ‘bad character’ in such a notoriously disreputable area accounts for the leniency shown to McCabe and Sherlock. Whatever the reason, the failure of the Court to severely punish a repeatedly violent offender who had been tried for this capital offence many times over under the same name—while others including ‘little Jenny’ daily felt the full arm of the law for the same crime and much less—meant Eleanor’s reign of terror in the laneways off Drury-lane could continue unabashed.

She was out of prison only five months before she was taken into custody again. This time, Eleanor—in concert with one Ann George and other unidentified nocturnal nymphs of St. Giles who were neither captured nor charged—had ‘feloniously assault[ed] John Harris’ in a house on Cross-lane.[66] The incident was the grand finale of a long night of libations to the king of spirits at the opening of a new public house nearby. Eleanor had never been one for subtlety, still, once in the privacy of the bedroom, she attempted to extend her repertoire to picking Harris’s pockets, with decidedly average results. For even in his inebriated state Harris realised what was afoot and ventured to depart, prompting Eleanor to return to her tried and true Buttock-and-Twang antics of yore; calling on two other women for assistance—including Ann George—while pushing her victim on to the bed, clapping one hand over his mouth and shoving the other into his pockets with a great deal less finesse. Her victim, who was ‘much in liquor,’ struggled against her, prompting Eleanor to sink her teeth into his cheek while some other grasping, unidentified hand purloined his money.[67] When a watchman arrived on the scene the victim ‘was in a very shocking situation; he was almost torn to pieces, and there was blood all round his lips.’[68]

There would be no more close calls, acquittals, conveniently absent prosecutors, or relatively short stays in the Bridewell before she was back to her old stomping ground of St. Giles. She would never again see the crooked, filthy laneways of home. Eleanor McCabe and Ann George were sentenced to seven years transportation to Africa at the Old Bailey on 11 May 1785.[69] It was a death sentence by another name, given the conditions for convicts sent to Africa in this period—only this death would be slow and drawn out compared to the speedy work of the hangman’s noose.

The Lady and the Prince

Incredibly, even as a transportee Eleanor’s lucky streak continued in a fashion. A year earlier, in April 1784, a ship load of convicts on board the Mercury had mutinied at the mere suggestion they were destined for African shores if the newly independent Americans refused to accept England’s cast-offs. It was the second time a convict mutiny had happened within an eight-month period on the strength of the African rumour.[70] By mid-1786, while Eleanor was still awaiting transportation, it was clear the African option would never be viable, forcing the British government to finally choose an alternate location for a penal colony: Kamay (Botany Bay).

To a woman whose life and crimes had played out within a five-minute radius of Drury-lane, where knowing every nook and cranny of that confusion of ‘tortuous’ alleys, cellars, and courtyards had been vital to her daily survival, Kamay (Botany Bay) must have seemed overwhelmingly far away.[71] Nevertheless, on 6 January 1787 Eleanor’s feet touched English soil for the last time as she was delivered on board the First Fleet transport Lady Penrhyn at Woolwich. When surgeon Arthur Bowes Smyth joined the ship in late March, he recorded her on his convict list as ‘Eleanor M’Cave, Trade: Hawker.’[72] Also recorded in the surgeon’s list of ‘Children, brot. out & Born on Board [sic]’ the Lady Penrhyn was an ‘infant’ named ‘Charles M’Cave.’[73] The child was clearly Eleanor’s but when he was born is less apparent, because he only appears on the 1790 copy of the surgeon’s journal. He may have been the child Eleanor gave birth to at Clerkenwell Bridewell in December 1782 or another child born to her in the interim.[74] Perhaps little Charles was even the namesake of Eleanor’s former accomplice and probable sibling, Charlotte McCave / McCabe.

Old habits being what they are, Eleanor and the many other members of her ‘bad trade’ on board the Lady Penrhyn carried on just as they had on dry land. At ten o’clock at night on 19 April 1787, for instance, Lieutenants George Johnstone and William Collins realised five of the convict women were absent from the ‘Women’s Births’ [sic].[75] They discovered four in no doubt compromising situations with sailors and another with the Second Mate Mr. Squires. The unidentified women were ‘put in irons’ for ‘this affair.’[76] Eleanor may have been one of those offenders. If not, then she had most certainly found some other, unrecorded opportunity for a maritime dalliance because she, too, fell pregnant after first boarding the ship and gave birth during the voyage—but Eleanor’s latest delivery did not occur on the Lady Penrhyn. On 6 August 1787, the Lady Penrhyn anchored at Rio de Janeiro for around a month, during which time Surgeon Bowes Smyth occupied himself dining on other ships in the Fleet, tending to people on land with medical complaints including ‘negro slaves’ and ‘going on Shore…collect.g some curiosity or other.’[77] In amongst these diverting activities it seems the surgeon failed to note in his journal the transfer of some of the Lady Penrhyn’s passengers to another in the fleet. So it was James Scott, Sergeant of Marines on the First Fleet convict transport Prince of Wales, who recorded in his own journal, Remarks on a passage to Botnay bay 1787 [sic], that on ‘August 29th, Wednesday four Female Convicts with one Child was changed to the [Prince] in lew of four. The[y] that Wee sent Was the Officers feverits, & often bread Disturbance in the ship [sic].’[78] Eleanor’s son Charles may well have been the child moved in that August transfer and Eleanor was certainly one of the four women swapped with the troublemakers on the Prince of Wales, for Sergeant Scott would also log in his journal on Saturday 24 November ‘At A.M, Elenor McCave a Convict Was Delivered of a Dead Child, Buried at [sea] [sic].’[79] The unnamed stillborn child was likely the belated victim of fevers that had struck down many of the convict women aboard the Lady Penrhyn a little over one month before Eleanor’s transfer to the Prince.[80]

All trace of ‘Charles M’Cave’ is lost but, with or without her little boy, Eleanor arrived at Kamay (Botany Bay) on board the Prince of Wales at 8 o’clock in the morning on 20 January 1788 and reached Warrane (Sydney Cove), Cadigal Country, on 26 January.[81] Eleanor and the rest of the convict women had to wait a while longer to disembark from their floating prison and board the longboats.[82] Before them was land and ‘the Men Convicts,’ who ‘got to [the female convicts] soon after they landed’—creating scenes which even amid the alien setting and searing heat of the Antipodean summer must have reminded Eleanor of the world she had left behind.[83]

A New Leaf and a Tree Change

Starting a completely new life in a new colony inspired some convicts to turn over a new leaf. Eleanor appears to have made this resolution in her own way, because around six months later on 31 August 1788—in quite a departure from her former profane lifestyle—she and Christopher Magee entered the holy state of matrimony at Warrane (Sydney Cove).[84] The following year, the couple welcomed a son. The little boy was, coincidentally or otherwise, given the same Christian name as one of Christopher’s old Scarborough shipmates, James Ruse, and baptised ‘James Magee’ at Sydney on 22 November 1789.[85] That same month, Ruse received permission to occupy an allotment of land at the ‘Rose Hill’ settlement further inland in Burramattagal Country. Inspired by the opportunities the new colony afforded, Ruse had agreed to apply his agricultural prowess to cultivating the small allotment to prove industrious convicts could help the colony become self-sufficient if granted land.[86] Like Ruse, Christopher Magee was still under sentence but had ‘recommended himself to [the Governor’s] notice by extraordinary propriety of conduct as an overseer’ and was, most importantly, ‘bred to husbandry.’[87] Nor was Christopher Magee averse to hard labour; he knew from his American experience what riches it could surely yield. But land had been scarce in the Chesapeake and beyond the reach of emancipated convicts; the opposite was true here in this brand new colony, especially since the colonists did not understand or acknowledge the First Peoples’ relationship and rights to the lands for which they had cared for millennia. Here, there seemed to be nothing preventing Magee from applying his considerable skills and making something of himself. Thus, he headed to Rose Hill with his family shortly after his newborn son’s baptism and Ruse’s own agricultural experiment commenced nearby.[88] We know this because, sadly, just over eight weeks later baby James Magee died and was buried at ‘Rose Hill, Port Jackson in the County of Cumberland’ on 31 January 1790.[89] With this commitment of mortal flesh to the earth, the land that had lately been serving as a cattle enclosure was transformed, evermore, into a burial ground (St. John’s Cemetery, Parramatta).[90]

The devastatingly premature demise of their son was the beginning of the burial ground and was by no means the end for the Magees either. Indeed, the Magees seemed determined to focus on moving forward, because on 30 January 1791—one day short of the first anniversary of their son’s burial—a daughter named Mary Magee was baptised at Rose Hill, which was renamed ‘Parramatta’ after the Burramattagal’s endonym a few months later.[91] By this time, Magee was placed on thirty acres on the south side of the creek leading to Parramatta, a ‘situation’ that Watkin Tench thought ‘very eligible, provided the river in floods does not inundate it.’[92] This truly would have been a ‘tree change’ for the former city-dweller Eleanor, but she must have risen to the challenge because the couple proved themselves to be every bit as skilled and hardworking as their neighbour James Ruse. By early December 1791, Tench could give a glowing report of Christopher Magee, who was clearly already planning to pattern himself on the successful tobacco plantation owners for whom he had toiled in America:

[H]e has no less than eight acres in cultivation, five and a half in maize, one in wheat, and one and a half in tobacco. From the wheat he does not expect more than ten bushels, but he is extravagant enough to rate the produce of maize at 100 bushels (perhaps he may get fifty); on tobacco he means to go largely hereafter. He began to clear this ground in April, but did not settle until last July. I asked by what means he had been able to accomplish so much? He answered, “By industry, and by hiring all the convicts I could get to work in their leisure hours, besides some little assistance which the governor has occasionally thrown in.” His greatest impediment is want of water, being obliged to fetch all he uses more than half a mile. He sunk a well, and found water, but it was brackish and not fit to drink. If this man shall continue in habits of industry and sobriety, I think him sure of succeeding.[93]

That was a big ‘if,’ as it turned out. Christopher evidently did not lack ‘habits of industry’; his undeniable talent for farming, managing labourers, and sheer hard work proved him worthy of being granted the land he had cultivated. He was the first person granted land at Camellia in Burramattagal Country on 22 February 1792, just two months after Tench’s visit.[94] ‘Sobriety,’ on the other hand, was another matter entirely.

Less than a year after his grant was registered, David Collins would give a very different account of the Magees as being ‘noted in the colony for their depravity’ and Christopher specifically as ‘wretched and rascally.’[95] Precisely how it all deteriorated so quickly—when Christopher finally had his own piece of land and all the evidence he and even the powers-that-be needed that he could be a success—is not clear. Yet it was common knowledge that the couple’s relationship was increasingly dysfunctional, characterised by frequent arguments and alcoholism. Quite apart from the invisible scars they carried from their formerly separate lives, what they recently experienced together had been trying enough: they had lost a baby son, Eleanor was nursing baby Mary and was soon pregnant with another. Perhaps she had grown weary of the physically tiring work of a ‘farmer’s wife’ in addition to the strains of motherhood and resorted to some of her former bad habits to cope. Christopher, too, had been implicated in some skullduggery with a seaman named Richard Sutton, which led to his character being paraded before the colonial court and found wanting.[96] A ‘gentleman’ witness claimed Christopher ‘did not consider an Oath binding’ and ‘was not of any Religion at all, but that of the Cock and Hens’—such blasphemy would have been shocking in a deeply religious society.[97] On the strength of this information, David Collins was apparently of the opinion that even in a largely convict population the Magees were as outstanding ‘in the general immorality of their conduct’ as they had been at farming.[98] Whether or not the Magees were more morally impaired than the rest or simply out of luck, a combination of alcohol, arguments, and aquatic travel at last proved lethal.

Drowned in Rum

Thirteen days before the third anniversary of baby James Magee’s death, Christopher and Eleanor tempted fate by ‘drinking and revelling’ with a convict named Mary Green in Cadi (Sydney) and heading for home in a small boat while under the influence.[99] Eleanor was six months pregnant at the time and had toddler Mary in her arms. The couple were ‘rioting and fighting with each other the moment before they got into the boat; and…[Eleanor]…imprecated every evil to befal her and the infant she carried about her, (for she was six months gone with child), if she accompanied [Christopher] to Parramatta [sic].’[100] As they neared Breakfast Point their little boat ‘heel[ed] considerably’ causing some water to get into a bag of rice belonging to Green, who instinctively moved to save it, and the boat overset.[101] That was all it took. This was how it all ended for the woman who had once attacked an innocent midwife in St. Giles, who probably lost a child in an English bridewell, squalid slum, en route to or in the colony, gave birth to a stillborn child at sea and buried a baby son at Parramatta when he was little more than a couple of months old. And as she ‘finally sunk’ beneath the surface of the Parramatta River, Eleanor knew the child she carried within her as well as Mary, the babe in her arms, would perish with her, too. Though Christopher successfully ‘wretched’ two-year-old Mary from Eleanor’s grasp at the last possible moment and got the toddler to the shore, ‘for want of medical aid [she] expired.’[102] Had the righteous Collins been fully apprised of all Eleanor had done in her thirty years of life, he no doubt would have been even more explicit in his insinuation that the ‘depraved’ Magees had merely gotten what had long been coming to them.

When Eleanor’s body was recovered a few days later, the godless ‘rascally’ Christopher Magee chose not the cemetery that already held his son but buried his wife, infant daughter and unborn baby ‘within a very few feet of his own door,’ perhaps where ‘cocks and hens’ routinely roamed.[103]

The profligacy of this man indeed manifested itself in a strange manner: a short time after he had thus buried his wife, he was seen sitting at his door, with a bottle of rum in his hand, and actually drinking one glass and pouring another on her grave until it was emptied, prefacing every libation by declaring how well she loved it during her life. He appeared to be in a state not far from insanity, as this anecdote certainly testifies; but the melancholy event had not had any other effect upon his mind.[104]

The alcohol continued to flow on the Magee farm in the months that followed. On Saturday 24 May 1793, a settler named Lisk had been carousing the night away there with ‘Rose Burk (a woman with whom he cohabited) until they were very much intoxicated.’[105] A drunken argument between the couple ensued as they made their way home on foot through the Parramatta township, ‘during which a gun that [Lisk] had went off, and the contents lodged in the woman’s arm below the elbow, shattering the bones in so dreadful a manner as to require immediate amputation.’[106] Christopher ‘had no further share than what he might claim from their having intoxicated themselves at his house’; however, as the second, alcohol-fuelled, almost fatal incident in the space of a few months, it ‘established him more firmly in the opinion of those who could judge of his conduct as a public nuisance.’[107]

Christopher Magee’s big dreams of being the owner of a tobacco plantation seemed to die with his young family. By the end of 1793 he and Ruse, ‘weary of independence,’ sold their farms and sought employment ‘until they could get away.’[108] Magee’s farm had sold for 100 pounds; an incredible sum to someone who had himself probably been sold at auction for less than 10 per cent of this price as a boy in America. According to Collins, in the wake of the sale Magee ‘was reduced to work as a hireling upon the ground of which he had been the master. But he was a stranger to the feelings which would have rendered this circumstance disagreeable to him,’ noted Collins, who shuddered at the thought that ‘this miscreant’ would now likely return to England ‘to be let loose again upon the public.’[109]

Magee did leave his baby James behind in the cemetery and his wife and daughter in their isolated grave near the banks of the Parramatta River at Camellia in Burramattagal Country. He must have thought better of returning to London, though. He had, after all, tried that before. He knew how that story ended. It probably occurred to him he would end up back in the colony again under sentence of transportation anyway. So, once more, he and James Ruse chose the same path. This time it led them to the Deerubbin (the Hawkesbury), where they were among the first twenty-two Europeans to ‘open ground on [its] banks…with much spirit.’[110] In 1800, he again sold his thirty acres and thenceforth was content to work for others until he was buried at St. Matthew’s Cemetery, Bulyayorang (Windsor), in 1815, aged 52.

* * *

Though baby James Magee did not live long enough to make a story of his own, when his tiny body was lowered into the earth on 31 January 1790 he also went down in history as the first person buried in the Parramatta Burial Ground, later known as St. John’s Cemetery, Parramatta. In accounting for how a mere babe of English and Irish extraction came to be buried in Burramattagal Country in the late eighteenth century, however, we have explored experiences and events of even greater global significance; the deprivation that led innumerable Irish people and so many others to migrate to London only to find themselves entrenched in more poverty in the metropolis; the resultant crime that subsequently gave rise to the institution of convict transportation and initially saw some 50,000 convicts forcibly removed to the American colonies where they were among the three quarters of more than half a million migrants who arrived there between 1700 and 1775 without their freedom and were sold for profit. This is a part of America’s history that, until recently, has been largely hidden or, at best, downplayed despite these significant numbers indicating that the peopling of the American colonies and the building of the United States of America was heavily reliant on British convicts, as it was later on in Australia.[111]

Via James Magee’s death we have also glimpsed, through his father’s eyes, the enslavement of African people and considered the American Revolutionary War from the perspective of someone on the ground in the Chesapeake: the home of so many of America’s liberty-loving ‘founding fathers’ who witnessed firsthand (and even owned) slaves, convicts, and indentured servants, signed the sacred text the Declaration of Independence and, in a few cases, went on to become the earliest presidents of the United States of America. We have also seen the fallout of their Revolution; particularly the fact that its outcome forced Britain to find an alternative ‘dumping ground’ for their ‘surplus’ English men and women. This, in turn, shed light on the agency of convicts who united and rose up when possible to prevent Africa from becoming their destination; actions which, in combination with other events, were catalysts for the historic journey of the First Fleet to what became the Colony of New South Wales.

The story of St. John’s first burial provided frequent reminders, too, that the agricultural opportunities the brand new Colony of New South Wales presented to the Magees and their ilk was contingent on the dispossession of the First Peoples, just as it had been in the Chesapeake. Here, then, notwithstanding the opportunity to begin afresh and the many changes for the better that were realised in the colony, there was often precious little that the New South Welshmen and women—whether convict or free, highborn or baseborn—would not take from or do to fellow humans to survive or, in some cases, merely turn a profit. In this respect, the otherworldly colony ‘beyond the seas’ was not so far removed from the worlds of the unscrupulous, money-grubbing British merchants who shipped and traded slaves, cons, and indentured servants for economic gain, the British colonists who owned fellow human beings on American plantations or, indeed, that of the saints and sinners of London.

CITE THIS

Michaela Ann Cameron, “The ‘Wretched,’ ‘Rascally’ and ‘Depraved’ Magees, and the Story of St. John’s First Burial,” St. John’s Online, (2019), https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/the-magees/, accessed [insert current date]

References

- David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Volume 1, (London: Printed for T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies, in the Strand, 1798).

- Adam Crymble, “The Most Catholic Street in England?” Migrant Histories: Understanding Georgian Lives on the Move, (2016) http://www.migrants.adamcrymble.org/2016/07/10/the-most-catholic-street-in-england/, accessed 15 February 2019.

- Judith Dunn, “The History of St. John’s Cemetery, Parramatta,” St. John’s Online, (2017), https://stjohnsonline.org/history/, accessed 15 June 2019.

- Tim Hitchcock, Robert Shoemaker, Clive Emsley, Sharon Howard and Jamie McLaughlin, et al., The Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 1674–1913 (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 19 June 2019).

- Tim Hitchcock, Robert Shoemaker, Sharon Howard and Jamie McLaughlin, et al., London Lives, 1690–1800 (www.londonlives.org, version 1.1, 19 June 2019).

- Richard Kirkland, “Reading the Rookery: The Social Meaning of an Irish Slum in Nineteenth-Century London,” New Hibernia Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, (Earrach / Spring, 2012): 16–30

- Locating London’s Past (www.locatinglondon.org, version 1.0, 19 June 2019).

- Edmund S. Morgan, “Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox,” Journal of American History, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jun., 1972): 5–29.

- James Scott, Remarks on a Passage to Botnay Bay, 1787 [sic], (13 May 1787–20 May 1792), State Library of New South Wales.

- Arthur Bowes Smyth, A Voyage to Botany Bay, 1787 (1787–1789), National Library of Australia, MS 4568, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-233345951, accessed 18 June 2019.

- The Digital Panopticon: Tracing London Convicts in Britain and Australia, 1780-1925, (www.digitalpanopticon.org, 19 June 2019).

- Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011).

- Anthony Vaver, Early American Crime: An Exploration of Crime, Criminals, and Punishments from America’s Past (http://www.earlyamericancrime.com/) (2019), accessed 18 June 2019.

NOTES

Special thanks to historian Dr. Anthony Vaver for his research assistance in the attempt to trace Christopher Magee’s movements on arrival as a transported convict in America. View Dr. Vaver’s wonderful website Early American Crime: An Exploration of Crime, Criminals, and Punishments from America’s Past (http://www.earlyamericancrime.com/) as well as his book, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011).

[1] Judith Dunn, The Parramatta Cemeteries: St. John’s, (Parramatta, NSW: Parramatta and District Historical Society, 1991), p. 7.

[2] Lewkner’s Lane (variously spelt Lukener’s Lane, Lewknor’s Lane, Lutener’s Lane, Lutenor’s Lane, Newtoner’s-Lane and Newtners-Lane) is present-day Macklin Street off Drury Lane. A Catholic school stands on or near the likely site of the crime. For a reference to the “notorious strumpets” of Lewkner’s Lane see Samuel Butler, Hudibras, Vol. II, (London: Charles & Henry Baldwyn, Newgate Street, 1819), Part III, Canto I, p. 345. See also note v. 866, accessed 16 February 2019. For a brief history of Lewkner’s Lane see George Clinch, Bloomsbury and St. Giles’s, Past and Present; with Historical and Antiquarian Notices of the Vicinity, (London: Truslove and Shirley, 7, St. Paul’s Churchyard, 1890), pp. 76–77. For other sources providing insight into Lewkner’s-Lane/Newtoner’s-Lane, see W. Nicoll, The London and Westminster Guide, Through the Cities and Suburbs, (London: 1768), p. 78, accessed 29 March 2019; R. and J. Dodsley, London and Its Environs Described, (1761), p. 318, accessed 29 March 2019; J. Nex and L. Whitehead, “The Insurance of Musical London and the Sun Fire Office 1710–1779,” Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 67: 199, accessed online 29 March 2019; W Edward Riley and Laurence Gomme (eds.), “Smart’s Buildings and Goldsmith Street,” in Survey of London: Volume 5, St Giles-in-The-Fields, Pt II, (London, 1914), pp. 18–22. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol5/pt2/pp18-22 [accessed 18 June 2019]; A New View of London: Or a Ample Account of that City in Two Volumes, Or Eight Sections, Volumes 1–2, (London: Chiswell, Churchill, Horne, Nicholson and Knaplock, 1708), p. 50.

[3] The ‘ruinous’ description and history of St. John’s Street as one of London’s most ancient streets comes from Walter Thornbury, Old and New London: A Narrative of its History, its People and its Places, (London and New York: Cassell & Company, 1887), p. 322.

[4] For reference to Hicks’s Hall’s ‘bulging walls’ see “St John Street: Introduction; west side,” in Philip Temple (ed.), Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, (London, 2008), pp. 203–21 via British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp203-221, accessed 18 February 2019. Regarding the historic trials hosted at Hicks’s Hall see Henry Benjamin Wheatley and Peter Cunningham, London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions, in Three Volumes—VOL. II, (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1891), p. 213.

[5] The description of Hicks’s Hall as ‘decrepit’ with ‘decaying brick’ and ‘rotten woodwork’ is a summary of information in primary sources associated with the sessions house held at the London Metropolitan Archives and cited in “St John Street: Introduction; west side,” in Philip Temple (ed.), Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, (London, 2008), pp. 203–21 via British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp203-221, accessed 18 February 2019.

[6] “Christopher McGee, 6 September 1773,” Middlesex Transportation Orders, Reference Number: MJ/SP/T/02/079, (London, England: London Metropolitan Archives).

[7] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), p. 60 [e-book]. Regarding ‘surplus’ British men and women see Edmund S. Morgan, “Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox,” Journal of American History, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jun., 1972): 16.

[8] Such ships were usually built with the transportation of precious, lucrative tobacco in mind rather than human cargo already deemed to be of the lowest sort. See Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), p. 89 [e-book].

[9] This section has been informed by Vaver’s research in “Chapter 5: Convict Voyages,” Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011).

[10] It is why the said merchants worked hard to wangle a contract with either the British government or with individual prisons to transport the convicted felons in the first place, even though transporting criminals across the Atlantic was risky, both to their personal safety on the high seas and, to a lesser degree, also financially. See Chapter 3: “The Business of Convict Transportation” in Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011).

[11] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), pp. 119–20 [e-book].

[12] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), pp. 120–21 [e-book].

[13] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), p. 6 [e-book].

[14] These efforts and embellishments did little to neutralise the effect of their blackened barely-there rags and skeletal appearance.

[15] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), p. 118 [e-book].

[16] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), p. 118 [e-book].

[17] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), p. 121 [e-book].

[18] Watkin Tench, entry dated 8 December 1791 in “CHAPTER XVI: Transactions of the colony until 18th of December 1791, when I quitted it, with an account of its state at that time,” A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, (Adelaide, South Australia: eBooks@Adelaide, University of Adelaide, 2014), https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/t/tench/watkin/settlement/chapter16.html, accessed 28 February 2019.

[19] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), p. 124 [e-book].

[20] Regarding the ‘sinke to drayen England of its filthe and scum’ see Nicholas Spencer to Lord Culpeper, 6 August 1676, Coventry Papers Longleat House, American Council of Learned Societies British Mss. project, reel 63 (Library of Congress), 170 cited in Edmund S. Morgan, “Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox,” Journal of American History, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jun., 1972): 21. For the “human serpents” see Americanus, “Felons and Rattlesnakes,” The Pennsylvania Gazette, 9 May 1751, via The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (http://franklinpapers.org/), (Digital Edition by The Packard Humanities Institute), http://franklinpapers.org/framedVolumes.jsp?vol=4&page=130a, accessed 22 February 2019. See also Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), pp. 148–49 for a discussion of the Americans’ complaints.

[21] Slaves and some of the last convicts sentenced to transportation were offered their freedom if they agreed to fight for the British against the rebellious colonists. Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011).

[22] It is not clear if it is the same person, but the date of the trial and incarceration is eight years and one month since his trial at Hicks’s Hall, so if he fell back into his criminal ways soon after arriving back in London, the dates are in keeping with Magee’s later claim to having spent eight years in America. London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), Middlesex Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents, (LL ref: LMSMPS507450054), Image 54, https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMSMPS507450054, accessed 19 February 2019; London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), Middlesex Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents: An Account of all the Prisoners that have been Committed to Tothill Fields Bridewell from July Session 1781 to October Session 1781 together with the Date of Commitment and Discharge and that have been Subsisted at the Rate of one penny each per Day by George Smith Keeper,” (LL ref: LMSMPS507450074), Image 74, https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMSMPS507450074, accessed 19 February 2019.

[23] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 7 July 1784, trial of CHARLES WILLIAMS (t17840707-7), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17840707-7, accessed 21 February 2019.

[24] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 7 July 1784, trial of CHARLES WILLIAMS (t17840707-7), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17840707-7, accessed 21 February 2019. For the point about the high visibility of his crime in the summer twilight, see Alan Atkinson, The Europeans in Australia: Volume I: The Beginning, (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2016), p. 234.

[25] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 7 July 1784, trial of CHARLES WILLIAMS (t17840707-7), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17840707-7, accessed 21 February 2019.

[26] James Joyce, Ulysses, (London: The Egoist Press, 1922), p. 590 via Internet Archive, accessed 21 February 2019.

[27] Daniel Defoe, The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders: also the Fortune Mistress or the Lady Roxana, (London: George Routledge and Sons; New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., 1906), p. 136, accessed 21 February 2019; Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), pp. 69–70 [e-book]. Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 7 July 1784, punishment summary of CHARLES WILLIAMS, (s17840707-1), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=s17840707-1, accessed 21 February 2019.

[28] As a Maid of Honour, Anne Boscawen had a salary of £300 from her initial appointment to the role on 9 February 1764. She vacated this role in November 1788 upon being promoted to Sempstress and Laundress to Queen, for which she had a salary of £500. She last occupied that position in 1818. The See “Maids of Honour: 1764 Boscawen, Anne,” and “Sempstress and Laundress: 1788 Boscawen, Anne” in “Household of Queen Charlotte, 1761–1818,” Institute of Historical Research, (School of Advanced Study, University of London,” https://www.history.ac.uk/publications/office/queencharlotte, accessed 21 February 2019. For some insight into the experience of being part of Queen Charlotte’s household see, Constance Hill, Fanny Burney at the Court of Queen Charlotte, (London: John Lane, the Bodley Head; New York: John Lane Company; Toronto: Bell & Cockburn, 1912), accessed 21 February 2019.

[29] “APPENDIX TO CHRONICLE. DEATHS.—Feb. [1831],” J. Dodsley, The Annual Register, Or A View of the History, Politics, and Literature of the Year 1831, (London: Baldwin and Cradock, 1832), p. 228, accessed 21 February 2019.

[30] Adam Crymble, “The Most Catholic Street in England?” Migrant Histories: Understanding Georgian Lives on the Move, (2016) http://www.migrants.adamcrymble.org/2016/07/10/the-most-catholic-street-in-england/, accessed 15 February 2019.

[31] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[32] Charles Knight (ed.), London, Vol. III (London: Charles Knight and Co., 1842), p. 267, accessed 14 February 2019. For the reference to close courts and garbage-filled paths, see John Timbs, Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis with Nearly Sixty Years’ Personal Recollections, (London: John Camden Hotten, Piccadilly, 1867), p. 379, accessed 14 February 2019. See also Richard Kirkland, “Reading the Rookery: The Social Meaning of an Irish Slum in Nineteenth-Century London,” New Hibernia Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, (Earrach / Spring, 2012): 16–30. As historian Anthony Vaver notes, “…this area was known for dangerous gangs, prostitutes, and rats. Gambling dens were everywhere. Fights often broke out in the taverns and gin shops that lined the street. One had to be fearless to walk through this tough neighbourhood, let alone live there. St Giles housed many of the Irish who came to London seeking work, because the parish had gained a reputation in Ireland as being generous with its poor relief. As a magnet for the Irish poor, St. Giles became a center for beggars and thieves, and it owned the record of being the parish with the largest number of crimes prosecuted at the Old Bailey, which is where criminals from London and Middlesex County were brought to trial. Estimates in 1750 claimed that at least one out of every four houses in St. Giles was a gin shop. People in rags roamed the street, many without shoes or stockings, and stray dogs sniffed the ground, seeking food among the decayed vegetables and filth that littered the streets. The lower classes…lived in dilapidated houses that always seemed on the verge of collapse. Such housing was classified into tenements, common lodging houses, or brothels. Most of these dwellings were windowless, due to a tax on the number of windows a house possessed. To avoid paying the tax, original windows were boarded up, which created dark and suffocating interiors. Working-class families lived in one room, and the very poor lived in either the cellar or the garret of a house. Three to eight people could share a bed together, and sheets were rarely replaced with clean ones. A large number of the poor lived in furnished rooms that were rented by the week, and lodgers desperate for money were sometimes caught pawning the contents of these dwellings.” Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), pp. 29–31.

[33] Lewkner’s Lane (variously spelt Lukener’s Lane, Lewknor’s Lane, Lutener’s Lane, Lutenor’s Lane, Newtoner’s-Lane and Newtners-Lane) is present-day Macklin Street off Drury Lane. A Catholic school stands on or near the likely site of the crime. For a reference to the “notorious strumpets” of Lewkner’s Lane see Samuel Butler, Hudibras, Vol. II, (London: Charles & Henry Baldwyn, Newgate Street, 1819), Part III, Canto I, p. 345. See also note v. 866, accessed 16 February 2019. For a brief history of Lewkner’s Lane see George Clinch, Bloomsbury and St. Giles’s, Past and Present; with Historical and Antiquarian Notices of the Vicinity, (London: Truslove and Shirley, 7, St. Paul’s Churchyard, 1890), pp. 76–77, accessed 16 February 2019.

[34] Eleanor McCabe was later described by a witness as living ‘all higley pigley’ with a number of females she committed crimes with in another dwelling in St. Giles. See Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 10 May 1780, trial of ALICE WILLOUGHBY, ELEANOR M’CABE, CHARLOTTE M’CAVE, ELISABETH GREEN (t17800510-48), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17800510-48, accessed 14 February 2019. For a contemporary reference to the subterranean inhabitants of the St. Giles cellars see Richard King, The New London Spy: Or, a Twenty-four Hours Ramble Through the Bills of Mortality. Containing a True Picture of Modern High and Low Life…The Whole Exhibiting a Striking Portrait of London, as it Appears in the Present Year, 1771, (London: J. Cooke, Pater-Noster Row, 1771), p.139, accessed 16 February 2019.

[35] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[36] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[37] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[38] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[39] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[40] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[41] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[42] The Middlesex Jury’s verdict ignored the testimony of Henrietta Evers, who recognised McCabe and Wright as the women who came with Jenny to fetch her mother that night.

[43] London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), Old Bailey Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents: The Information of Catherine Hobdy of Newton Lane St. Giles’s Spinster taken before me this 18th. day of January 1781, (LL ref: LMOBPS450240022), Image 22 of 517, https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMOBPS450240022, accessed 16 February 2019.

[44] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 22 February 1781, trial of JANE VINCENT, ELEANOR M’CABE, MARY LILLY, and MARY WRIGHT (t17810222-44), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17810222-44, accessed 14 February 2019.

[45] Jane “little Jenny” Vincent was executed on 6 June 1781. Digital Panopticon (https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/, version 1.1), Jane Vincent Life Archive (ID: obpt17810222-44-defend506), https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpt17810222-44-defend506, accessed 16 June 2019.

[46] “Thursday and Friday’s Posts. LONDON, June 7,” Northampton Mercury, 11 June 1781, p. 2. “Yesterday Morning the following Malefactors were carried from Newgate, and executed at Tyburn, viz. Jane Vincent, for robbing Mrs. Anne Evers, in a House in Newtoner’s-Lane, of a Guinea, two Gold Rings, and other Property;…They all acknowledged the Justness of their Sentence. Vincent in particular confessed that the Scheme for which she suffered, was not the first of the Kind wherein she was concerned; that it was a common Practice with her, and her Companions, to take Persons into their Apartments, under various Pretences, and rob them.”

[47] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 10 May 1780, trial of ALICE WILLOUGHBY, ELEANOR M’CABE, CHARLOTTE M’CAVE, ELISABETH GREEN (t17800510-48), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17800510-48, accessed 14 February 2019.

[48] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 10 May 1780, trial of ALICE WILLOUGHBY, ELEANOR M’CABE, CHARLOTTE M’CAVE, ELISABETH GREEN (t17800510-48), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17800510-48, accessed 14 February 2019; Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 10 May 1780, punishment summary of ALICE WILLOUGHBY, ELEANOR M’CABE, CHARLOTTE M’CAVE and ELISABETH GREEN (s17800510-1), accessed 14 February 2019; London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), City of London Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents: Middlesex Commitments, 19th October 1776—6th December 1780, (LL ref: LMSLPS150910118), Image 118 of 376, https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMSLPS150910118, accessed 18 February 2019; London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), City of London Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents: Middlesex Commitments, 26th of June 1780–8th of December 1781, (LL ref: LMSLPS150920046), Image 46 of 381, https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMSLPS150920046, accessed 18 February 2019.

[49] London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), Middlesex Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents: A LIST of the Number of PRISONERS who have been released from Clerkenwell Bridewell, in Consequence of the Riot on Tuesday of Sixth of June, 1780, June 1780 (LL ref: LMSMPS507260050), Images 50–51 of 107, https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMSMPS507260050, accessed 18 February 2019. The Gordon Riots lasted several days and were fuelled by anti-Catholic feelings and policies. As Danielle Thyer noted, “the Gordon Riots of 1780…led to the death of 285 people and exacerbated the already fraught relations between Protestant and Irish Catholic agitators.” See Danielle Thyer, “Hugh Hughes: The Wheelwright Made Right,” St. John’s Online, (2016), https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/hugh-hughes/, accessed 16 June 2019 and Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker, London Lives: Poverty, Crime and the Making of a Modern City, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 343.

[50] The paraphrased “lovely ladies waitin’ in the dark” is, of course, a reference to Alain Boublil, Jean-Marc Natel and Claude-Michel Schönberg, “Lovely Ladies,” Les Misérables, (1980), Act I.

[51] Richard King, The New London Spy: Or, a Twenty-four Hours Ramble Through the Bills of Mortality. Containing a True Picture of Modern High and Low Life…The Whole Exhibiting a Striking Portrait of London, as it Appears in the Present Year, 1771, (London: J. Cooke, Pater-Noster Row, 1771), p.144, accessed 16 February 2019.

[52] Richard King, The New London Spy: Or, a Twenty-four Hours Ramble Through the Bills of Mortality. Containing a True Picture of Modern High and Low Life…The Whole Exhibiting a Striking Portrait of London, as it Appears in the Present Year, 1771, (London: J. Cooke, Pater-Noster Row, 1771), p.144, accessed 16 February 2019.

[53] London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), Old Bailey Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents: The Information of John Mathew…Taken before me Charles Triquet Esquire…the Ninth day of August 1781, (LL ref: LMOBPS450240355), Image 355 of 517, https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMOBPS450240355, accessed 16 February 2019.

[54] London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), Old Bailey Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents: The Information of John Mathew…Taken before me Charles Triquet Esquire…the Ninth day of August 1781, (LL ref: LMOBPS450240355), Image 355 of 517, https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMOBPS450240355, accessed 16 February 2019. The case appears to have gone to trial, as London Lives holds a document “Information about Documents Concerning Old Bailey Trials” that records Mary Bowen was tried at the Old Bailey on 12 September 1781 for stealing a watch. See London Lives 1690 to 1800 (https://www.londonlives.org/, version 2.0), Old Bailey Associated Records: Information about Documents Concerning Old Bailey Trials, 12 September 1781, (LL ref: assocrec_168_16797), https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=assocrec_168_16797, accessed 16 February 2019, However, there is no record of the trial in the Old Bailey Online database.

[55] Anthony Vaver, Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America, (Westborough, Massachusetts: Pickpocket Publishing, 2011), p. 31 [e-book].

[56] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 10 April 1782, trial of ELEANOR M’CABE and ANN SHERLOCK (t17820410-11), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17820410-11, accessed 16 February 2019.

[57] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 10 April 1782, trial of ELEANOR M’CABE and ANN SHERLOCK (t17820410-11), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17820410-11, accessed 16 February 2019.

[58] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0), 11 September 1782, trial of ELEANOR M’CABE (t17820911-68), https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?div=t17820911-68, accessed 16 February 2019.