By James Dunk

Supported by a Create NSW Arts and Cultural Grant – Old Parramattans & Rogues

WARNING: This essay discusses suicide, which may be distressing to some readers. Reader discretion is advised.

On New Year’s Day, 1811, Nicholas Bayly, Charles Hook, and Gregory Blaxland, Esquires, marked the first anniversary of Lachlan Macquarie’s administration as governor of New South Wales. Representing ‘other principal inhabitants’ of the settlements, they lauded the man who had already done so much ‘to relieve the people from those disasters and calamities under which they had long struggled.’[1] They pledged that every approach to His Excellency would give them ‘a fresh source of happiness and satisfaction,’ and he, in turn, ‘looked forward with confidence’ to their continuing good will and support for his measures.[2]

A year later, the same gentlemen, together with two more ‘principal inhabitants,’ Alexander Riley and Garnham Blaxcell, paid another tribute to Macquarie on the Queen’s Birthday. The bells rang out through the town, the Royal Standard flew at Fort Phillip and the Union Jack from the Dawes Battery. All the ships in the harbour were decked out in their colours. Many colonists had gathered at the public marketplace as the new year broke, and the five men conveyed their collective pleasure, their ‘exultation at the happy period that is dawning on our prospects.’[3] Daily, they said, they could look out on the great distance between them and their sovereign with ‘decreasing regret.’[4] A royal salute sounded from Tar-Ra (Dawes Point), the 73rd Regiment offered three volleys for her Majesty, and ‘Lo!’ the poet laureate broke into verse, ‘from the East, with brilliant ray,’[5]

Majestic breaks the god of day!

And proud of this distinguish’d morn,

With lengthen’d lustre gilds the dawn:

The chearful hills — the golden vales,

The verdant fields, and waving dales,

Enrich’d by nature’s liberal hand,

Pour plenty o’er the smiling land’[6]

It was all very decorous. But the serene winds carried the fine words of Michael Robinson, Australia’s first and only poet laureate, over country that had been carefully tended for hundreds of generations. All the pomp of the empire could not quite erase the violence of the dispossession of the country’s Indigenous people. Bayly and the others hinted as much when they spoke of ‘the rude and unconnected state consequent and inseparable from the first efforts of colonization [sic].’[7]

These fine words and the flags snapping in the wind also worked to erase a more immediate violence for the fledgling colony—the two years of turmoil following the arrest of the governor, William Bligh, on 26 January 1808. In that act, the officers of the New South Wales Corps had been supported by many of the wealthier colonists, and together they gathered wealth and power to themselves in a breathtaking carnival of imperial chaos. Four of the five ‘principal inhabitants,’ excluding Hook, benefited from lucrative appointments and lavish grants of land during the Usurpation. Each, save Hook, was publicly named by a furious Bligh when he declared the colony in a state of mutiny. Hook, for his part, was fined £50 and thrown into prison for distributing this declaration of the underground governor.[8]

Perhaps the colonists really were united behind Macquarie at first; perhaps they really did hope for a new and more pacific era, but their history of violence did not stay buried.

Charles Hook never recovered from the ravages of those years, and retired after several years of struggle to his estate, in near bankruptcy.[9] Blaxcell fled the colony in heavy debt, and drank himself to death in Jakarta.[10] Riley’s brother killed himself in 1825, apparently suffering from severe depression, and Blaxland, after decades out of the public gaze, took his life on New Year’s Day, 1853. As for Nicholas Bayly, though he really was, for a time, one of the principal inhabitants of the colony with a good deal of land and money in his hands, he was never satisfied, and never successful. Perhaps he was a poor match for the colony. Others seemed to make the most of the freedoms and opportunities of their colonial setting. They took their free land from Aboriginal People, free convict labour, free seed, free stock, free food. They traded astutely, farmed wisely, made money, and built up small and great estates and left much more to their children than they had inherited. But Nicholas Bayly took one wrong turn after another, almost from the outset.

Of Earls and Generals

It was not as though Bayly was born into bad luck. In 1769, the year he was born, his uncle Henry became a baron and took the name Paget. Fifteen years later, Lord Paget was made the first Earl of Uxbridge, and was later Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire, Constable of Caernarfon Castle, Ranger of the Forest of Snowdon, Steward of Bardney, Vice-Admiral of North Wales. He was succeeded by his son, Henry William, who gained such accolades he was given command of the cavalry at Waterloo, where he lost a leg.[11] Henry William was made Marquess of Anglesey, a knight in the orders of the Garter and the Bath and in the Royal Guelphic Order, and served as Lord High Steward of England and Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland. He is remembered by a 27-metre statue near the family seat, at Plas Newydd.[12]

Plas Newydd Anglesey House NW view, by Waterborough (2013), (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

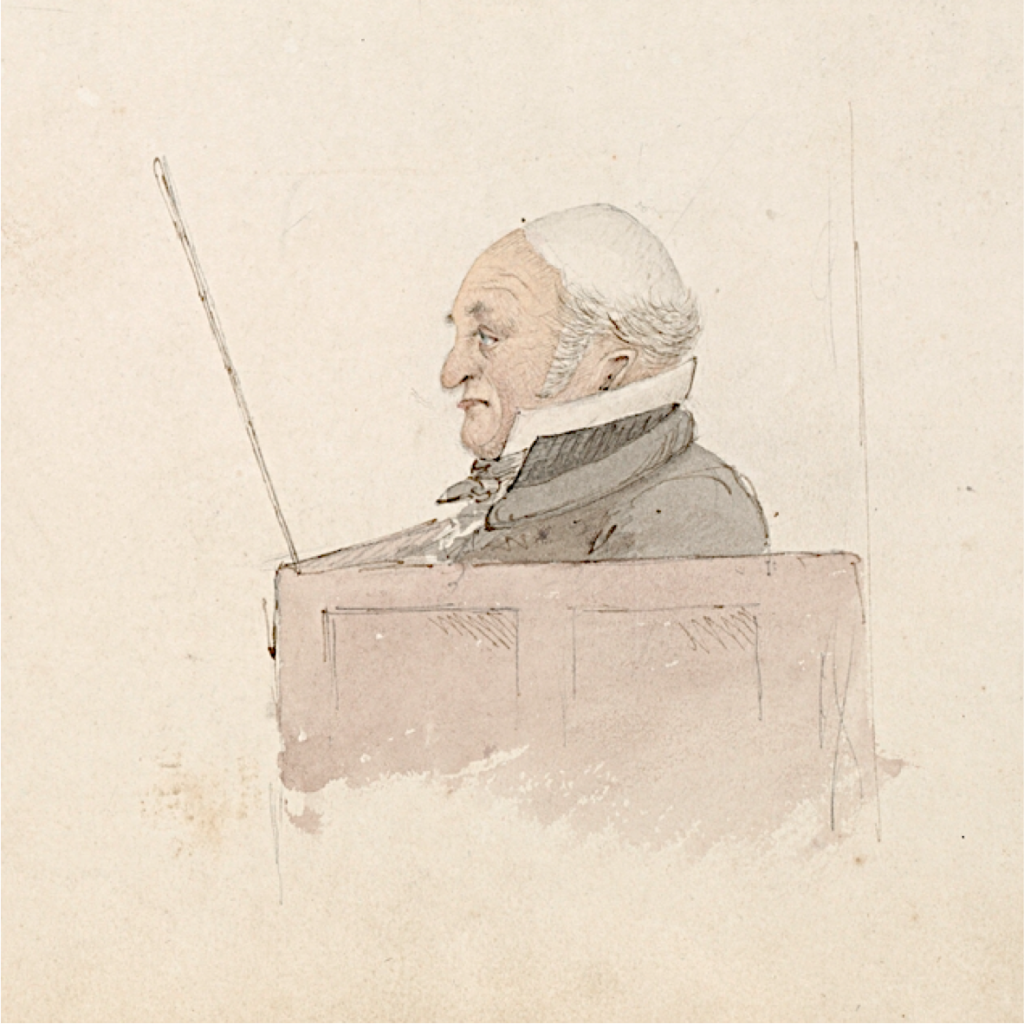

The Marquess’s cousins, who also sprung from Plas Newydd, did not achieve quite such heights, but they followed in the same general direction. Bayly’s father, also Nicholas (1749–1814), was a lieutenant-colonel and M.P. for Anglesey.[13] His brother, Henry, had entered the army on 12 April 1783 as an ensign of the 88th Regiment of Foot, fought in Flanders, Holland, and Ireland, and was quickly promoted: lieutenant, captain, colonel. He was wounded in the hand whilst carrying his regiment’s banner, and promoted again. He was private secretary to the British Minister to the Portuguese Court, aide-de-camp to the Prince Regent, and then Lieutenant Governor of Guernsey.[14] He died an old man, a general, in Dover Street, Piccadilly. Bayly’s other uncles, Edward and Charles, were colonel and lieutenant-colonel respectively.

The Corps and the Court-Martials

The illustrious Paget-Bayly family helped Nicholas Bayly procure an ensign’s commission without purchase, and he enlisted in the New South Wales Corps. He sailed for Cadi (Sydney) late in 1797, at the age of twenty-eight, as commander of the guard on the ship Barwell. There was some kind of conspiracy to seize the ship during the voyage, which led to Bayly arresting his junior officer, Ensign George Bond. On arriving in Cadi (Sydney), Bond was allowed to resign rather than face court-martial.[15] Such maritime dramas constituted a real threat. A mutiny had broken out near Rio de Janeiro aboard the Lady Shore, which had sailed just prior to the Barwell. The convict women it carried were disembarked to be domestic servants in Montevideo, and several soldiers of the Corps became prisoners of war by the Spanish in Buenos Aires.[16]

In the colony, Bayly made a good start. He received two land grants in 1799 and 1800, totalling 550 acres, at Wallumatta, or ‘Eastern Farms,’ between Moco Boula (Hunters Hill) and Parramatta.[17] He soon, however, became embroiled in the quarrels to which the colonial community was vulnerable. Because civil juries were not thought advisable amongst a population dominated by criminals, military officers were seconded as judges. In June 1799, Bayly was a member of the court that decided a case, which the Hawkesbury settler John Bowman brought against his assigned convict William Chickley, was malicious. A year later, Bayly charged Bowman with defaming his good character. Chickley was his lead witness. ‘Amongst other abusive language,’ Chickley and two others swore Bowman had said ‘that he knew Mr Bailey was as great a thief as any in the country, that he knew him to be a thief before he came here,’ and that he could prove it.[18] When it came to it, Bowman could not, and was fined £20 and sentenced to six months in gaol.[19]

*

Those who planned the structure of New South Wales society hoped that Her Majesty’s officers might serve well enough as upstanding citizens. The majority of the officers, however, had purchased their commissions and saw them, with reason, as expensive investments.[20] They were at first the only part of the forming society with any real income or assets, which they leveraged using their coercive power to set up highly lucrative schemes. At first subtle, these became more overt after the departure of the first governor, Arthur Phillip, while their own senior officers administered the colony. Alcohol was a core component of the earlier schemes: ‘regulating alcohol was one of the central challenges of the colony,’ writes historian Matthew Allen.[21] For the first two decades, every governor tried to follow their orders from London to control the trade, and their continuing failure undermined their administrations. Alcohol flowed freely, and there was a great deal of drunkenness. This made the convicts disorderly and perhaps more disposed to crime, but it was the trade itself that posed the greatest problem by undermining the governor’s authority. It helped create a commercial elite composed entirely of the officers of the New South Wales Corps. This meant that, instead of supporting colonial government, they tended to act in their own interests. The governors’ failure to regulate the trade, argues Allen, ‘became a symbol of the colony’s disordered state.’[22]

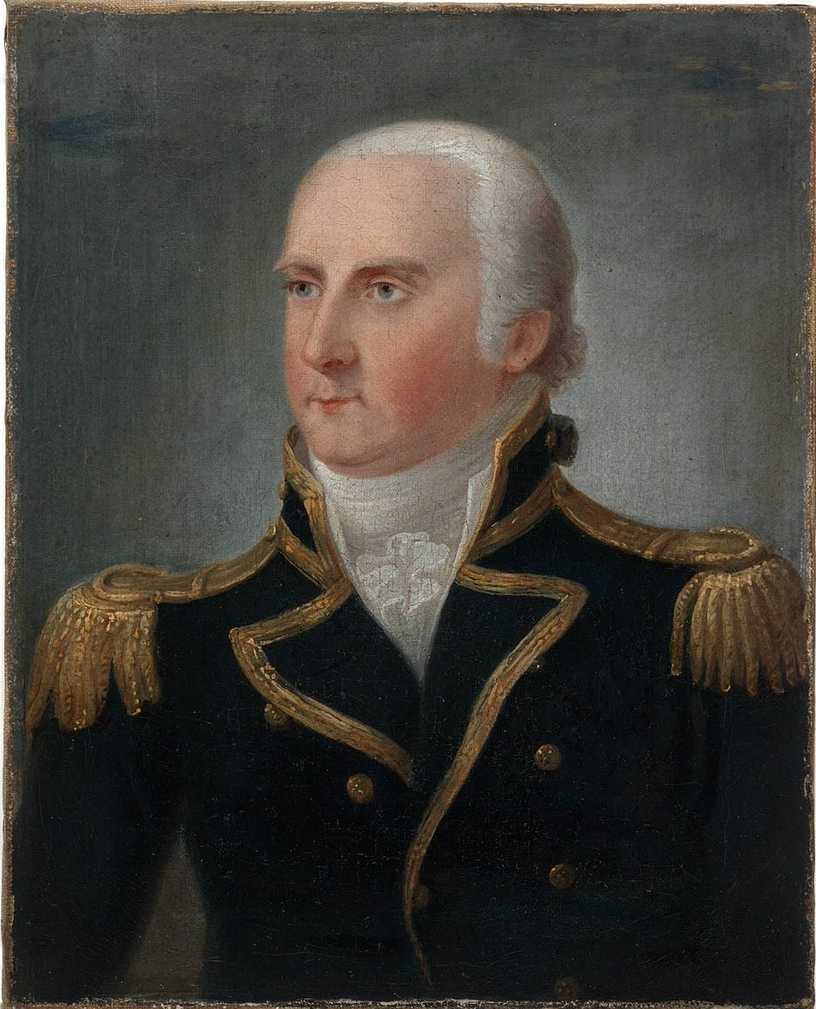

Governor Philip Gidley King tried particularly hard to dampen the rum trade. On becoming governor he quickly issued a general order banning the officers from any involvement in the trade, which aligned with a direct order from the head of the army, the Duke of York.[23] This would put Ensign Nicholas Bayly in the way of conflict and discipline, and down a path which ended in his ignoble exit from the Corps. On 28 December 1801, Governor King searched the premises of Simeon Lord, whom he saw as a leading player in the trade—a dealer, agent, and smuggler, enabling and corrupting the officers. During the search, a cask was discovered with what was left of sixty gallons of spirits from the ship Majorca that King had assigned to Bayly ‘for his domestic purposes.’[24] Each officer received 40 gallons or more per year as a standard indulgence. Lord admitted he was Bayly’s agent and that he had instructions to issue the liquor when and to whom Bayly directed him. The broad-arrow ‘king’s mark’ was placed on the cask and it was confiscated. That afternoon, King issued a fresh general order referring to the ongoing trade amongst the officers and again condemning it.[25] Bayly wrote to the governor to protest that Lord was only holding the spirits for him because they were liable to be stolen from the barracks, and that he had no knowledge of the prohibition against officers trading in alcohol as he had been on Norfolk Island when it was issued—but that, as King pointed out, was no excuse. In a second letter to his commanding officer, William Paterson, Bayly suggested that Governor King’s general reprimand besmirched the honour of all the officers; that if King was referring to him specifically he should identify him by name; and that, now identified by name without cause, he expected Paterson to seek redress on his behalf.[26] King had Paterson assemble the civil and military officers of the colony that Sunday morning, at eight o’clock, and read a series of orders and instructions, to make everything perfectly clear. Bayly refused to attend, for which he was court-martialled on 11 January 1802 and sentenced to a public reprimand in front of the entire corps.[27]

The dressing-down may have had unintended consequences. On 22 January, Bayly severely beat and horsewhipped his servant. He had been in the habit of handing out such extrajudicial punishment, which contravened another of the governor’s orders, as well as most codes of honour and morality. Decades later it would be argued that assigning convicts to colonist ‘masters’ morally compromised those colonists.[28] How much more, then, this mixture of economic privilege and coercive power? Bayly, as before, was either unaware of King’s orders or had no interest in complying with them. He was suspended from his rank and pay for three months.[29]

The Puppeteer

The young ensign’s prospects might have seemed dire, but he had made two important alliances in the Corps. Late in 1801, he had married Sarah Laycock, the daughter of the quartermaster. He had also come under the influence of John Macarthur, who was the Corps’s paymaster, but also the most intense, difficult, and powerful figure in the colony for four decades.

Macarthur was involved in constant skirmishes with a succession of governors and drew Bayly into them. He had sent a sharp critique of Governor John Hunter to the Secretary of State and the Commander-in-Chief, and Hunter, on being recalled, warned his successor of this ‘restless, ambitious and litigious’ man.[30] Macarthur took a disliking to King in turn, and eventually convinced the officers to boycott him socially. When Macarthur tried to co-opt Paterson, his superior, into the boycott he overplayed his hand—something to which he was occasionally prone. The result was a duel between the two in September 1801, which Macarthur won, wounding Paterson in the shoulder. King had Macarthur arrested for sowing discord, but took the unusual and inefficient step of sending him to England for court-martial because he was certain Macarthur would triumph in any colonial trial.[31] These were untenable conditions in which to govern. On 8 November 1801, King wrote a private letter to the Colonial Office: ‘I need not inform you who or what Captain McArthur is. He came here in 1790 more than £500 in debt, and is now worth at least £20,000.’[32] During that time, wrote King, Macarthur had employed himself ‘making a large fortune, helping his brother officers to make small ones (mostly at the publick expence), and sewing discord and strife…Many and many instances of his diabolical spirit had shown itself before Gov’r Phillip left this colony, and since,’ King wrote darkly, ‘altho’ in many instances he has been the master worker of the puppets he has set in motion’ [sic].[33] One of those puppets was Nicholas Bayly. Conveying news of the court-martials of Bayly in March, as Macarthur sailed to England for court-martial, King complained that he and Paterson had had to deal with ‘much vexatious and unwarrantable treatment from Ens’n Bayly and the officers who are become the partisans of Capt’n McArthur.’[34] The influence spread from the officers to the soldiery, as William Gore would later write: ‘every means that intrigue and artifice could suggest were resorted to by him and his adventuring needy associate Bayly to effect the object they had in view. The junta now tampered with the soldiers, who became the dupes of their favoritism [sic], and their minds were withdrawn from their allegiance by the most alluring and insidious promises and misrepresentation.’[35] Driven by the hope of profit, scheming and unruly, King concluded that the officers and soldiers of the Corps could hardly produce that order and discipline so necessary in ‘this distant part of His Majesty’s dominions.’[36]

The officers continued Macarthur’s war in his absence. King had to travel to the outer settlements and was gone four weeks late in 1802. He took ill on his return, and during that illness a series of scurrilous drawings and ‘pipes’ (satirical poems) appeared, targeting his character and administration. Four were discovered in the possession of the Corps, including a rather nasty poem, ‘Anticipation, or Birthday Ode’, kept in a chaise belonging to a lieutenant. In the yard between the barracks of Bayly and Captain Kemp a rather blunter piece was found, called ‘Extempore Allegro’:

My power to make great

O’er the laws and the State,

Commander-in-Chief I’ll assume;

Local rank, I persist,

Is in my own fist,

To doubt it who dare shall presume.

On Monday keep shop,

In two hours time stop,

To relax from such kingly fatigue,

To pillage the store

And rob Government more

Than a host of good thieves—by intrigue.

For infamous acts from my birth I’d an itch,

My fate I foretold but too sure;

Tho’ a rope I deserved, which is justly my due,

I shall actually die in a ditch—

And be damned![37]

Whether they wrote them or only took delight in reading them aloud and sharing them around, it was clear that the officers had become very partisan indeed.[38] All three officers were court-martialled, with some difficulty, since there were fewer and fewer officers available to sit in judgement and less who could be trusted not to be partisan.

In 1793, Bayly’s brother Henry had been promoted to captain in the Coldstream Guards after distinguishing himself during the Siege of Valenciennes.[39] Word had no doubt reached Cadi (Sydney). Bayly had been—routinely—promoted to lieutenant in 1802, whilst trading in spirits, ridiculing the governor, and beating his servants. This he continued to do, in spite of his trial and sentencing, and in such a public way that King could hardly avoid the challenge to his authority. Bayly was court-martialled again in February 1803, and yet again in March. The court made no investigation even though, according to King, Bayly freely confessed to (or boasted of?) the crime.[40] The officers decided that the charge was ‘not within their cognizance,’ and honourably acquitted Bayly.[41] King, no doubt fatigued by the constant battles, deemed it ‘expedient’ to suspend his own orders prohibiting extrajudicial beating, while at the same time making clear that any person, convict or free, had legal redress for assault and other abuses, and that anyone who bypassed the magistrates and meted out their own discipline to convict servants would not receive free labour in future.[42] The Judge-Advocate General, after reviewing the documents, observed that the officers were wrong to have acquitted Bayly, since they had not tried him and yet, ‘for the sake of harmony…His Majesty rather chooses to pass over any seeming irregularity in the proceedings and to recommend to all persons concerned that they will consign to oblivion, if it be possible, all that has passed.’[43]

Bayly, in any case, had resigned his commission in September 1803. The circumstances are not clear, but likely had to do with his steady stream of disobedience and misbehaviour. He turned his attention to his estates: he had the two grants at Eastern Farms and somehow managed to secure a further 480-acre grant from King, which covered present-day Haberfield.[44] He named the new estate ‘Sunning Hill.’[45] Bayly was appointed to committees for repairing roads and assessing the damage after a flood at the Hawkesbury—not glorious positions, certainly, but perhaps an indication of reconciliation.[46] King was tired. He had requested a reprieve and was replaced in August 1806 by William Bligh. Macarthur, who had returned to the colony as a free settler with powerful new patrons, found Bligh worse by far than his predecessors, bent as he was on a more strict subordination of the wayward officers and settlers to imperial authority. Their feud led to a political conflagration which has been called the ‘Rum Rebellion,’ ‘Little Revolution,’ and the ‘Usurpation,’ and it is well known.[47]

Anarchist Junto

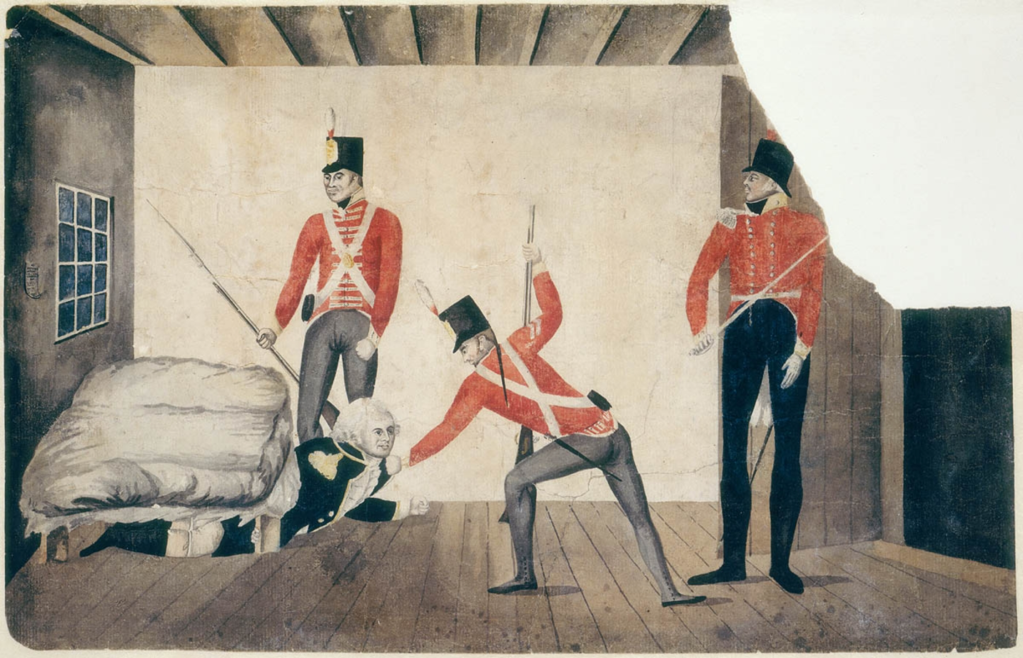

Less well known is the key supporting role played by Nicholas Bayly. He and Garnham Blaxcell offered bail for Macarthur during the legal dance of December 1807 and January 1808 which precipitated Bligh’s deposal. On 24 January, the bailsman and Macarthur’s cousins dined with the officers of the New South Wales Corps, while Macarthur spent the evening walking to and fro on the parade ground nearby.[48] On the 25th, everything was put into motion, and on the 26th, the officers marched on Government House.

Bayly was at the centre of things, as the Commissary, John Palmer, indicated in his description of the ‘infamous and villainous plans’ carried out by ‘the self appointed Lieutenant Governor, with the assistance of Messrs. McArthur, Baily [sic] and others of the Rebellious Party.’[49] Bayly was appointed ‘private secretary’ to Acting Lieutenant-Governor George Johnston directly after the deposal. He helped to search Government House for evidence of tyranny and would later be asked to account for the books and papers he had confiscated.[50] Now, wrote Palmer, the rebels were ‘going about the country and endeavouring by every, artful means in their power to extort affidavits from all descriptions of persons that would alledge [sic] any thing against the Governor or those that were attached to the Government.’[51] Many years later Bayly’s prominence in the rebellion was testified to by George Suttor, botanist, farmer, and sometime superintendent of the asylum at Mogoaillee (Castle Hill), as he set down his memoirs.[52] Suttor was ‘attached to the governor’ by disposition, and was imprisoned and fined by the rebels after he refused to attend a muster and then used certain choice expressions to describe the acting (rebel) governor. Suttor wrote in his memoirs that the rebellion had been orchestrated by a ‘triumvirate’ of Macarthur, Bayly, and Edward Abbott, a captain in the Corps. The senior lawyers asked for advice about the British response to the ‘little revolution’ in Cadi (Sydney) seemed to think Bayly the person of most interest after Macarthur. The two were at the top of the list of people they wanted investigated, those who appeared to have ‘concerted together with Major Johnston’ before the arrest and then helped him assume government: ‘John McArthur, Nicholas Bayly, Doctor Townson, John Blaxland, Garnham Blaxcell, and Thomas Jamieson.’[53]

As well as private secretary to the acting governor, Bayly was appointed to the position of Provost Marshal, responsible for carrying out legal sentences—a crucial one, in the legal turmoil unfolding. He does not appear to have executed these responsibilities in the pursuit of justice. During the height of the disorder, thirteen Hawkesbury settlers penned a memorial to the Secretary of State to distance themselves from the rebel cause—and explain the various ways they had suffered by it. They also offered an astute explanation for the rebellion. By re-establishing discipline and protecting sobriety and industry, they argued, Bligh had fallen afoul of a set of officers who were actively disrupting the agricultural pursuits of small settlers to strengthen their own positions. Those small settlers had no protection, since the rebels had sacked all the decent magistrates following their coup, and if they appealed to the acting governor they were liable ‘to be dragged to prison by convicts and locked up without meat, drink, fire, or candle, or even straw to lye [sic] on, with the most abandoned thieves.’[54] The settlers pointed to the case of poor John Bowman, whom Bayly had prosecuted in the relative calm of the year 1800. In 1808 Bowman had charged one of his servants with a felony, and though he had acknowledged his guilt before a magistrate he had been acquitted because Bowman’s witnesses had not been summoned by the Provost Marshal. Instead, the Provost Marshal—Bayly—had promised to support the convict in a suit against Bowman for false imprisonment. In February 1809, Bowman was tried for calling Bayly a rogue. Bowman had been locked in a cell with three men who were under sentence of death, tried, fined, and returned to the same cell to serve his sentence.[55] The episode suggests Bayly was vindictive as well as unscrupulous.

Bad blood lingered between Bowman, who was a leader amongst the loyalist settlers, and the Corps.[56] William Wood, a soldier in the Corps, printed an advertisement in the Sydney Gazette announcing that Bowman had scandalously misrepresented him as a person of bad character, and while this would have simply incurred his contempt, it had become clear that Bowman meant to ‘injure [his] circumstances in life’ and so Wood ‘fully intended to seek legal redress.’[57] Between August and November that year, in at least four public auctions on Bowman’s premises, Bayly sold off the poor man’s property to pay his debts: wheat, a mare, a number of pigs, sheep, and goats, a ‘capital young horse.’[58]

The settlers voiced their dissent in more creative ways. These included ‘A New Song,’ penned by convict attorney Lawrence Davoren and circulated during the years of the Usurpation, to be sung to the air ‘Health to the Duchess’:

The voice of rebellion resounds o’er the Plain.

The Anarchist Junto have pulled down the banner

Which Monarchical Government sought but in vain

To hold as the rallying Standard of honor,

The Diadem’s here fled

From off the Kings head[59]

Macarthur and Johnston featured, as ‘Jack Boddice,’ a charming reference to his early career in drapery, and his ‘fool,’ Johnston, ‘that Turnip head tool.’[60] There are a few lines reserved for Bayly: ‘The Carmagnol Mayor / Has here got an heir / His name and his crimes still to perpetuate.’[61] The carmagnole, writes Bruce Baskerville, was a popular song of the French Revolution associated with the first mayor of Paris during the revolution, Jean Bailly. An astronomer and freemason, Bailly had been a key leader of the revolution, presiding over the Tennis Court Oath and, writes the poet in a note, ‘principal in the murder of Lewis 16th, a creature of Robespierres.’[62] He himself was sacrificed in time. The poet added a note on ‘his hopeful namesake,’ Bayly, who had ‘been no less active in putting down monarchy here, being a principal in the rebellion now existing.’[63] Bligh, too, invoked the terror to describe Bayly: that ‘self-created Lieutenant-Governor’s secretary’ who had turned up at Government House.[64] ‘He read and delivered a paper to me,’ wrote Bligh, ‘in a very Robesperian manner.’[65]

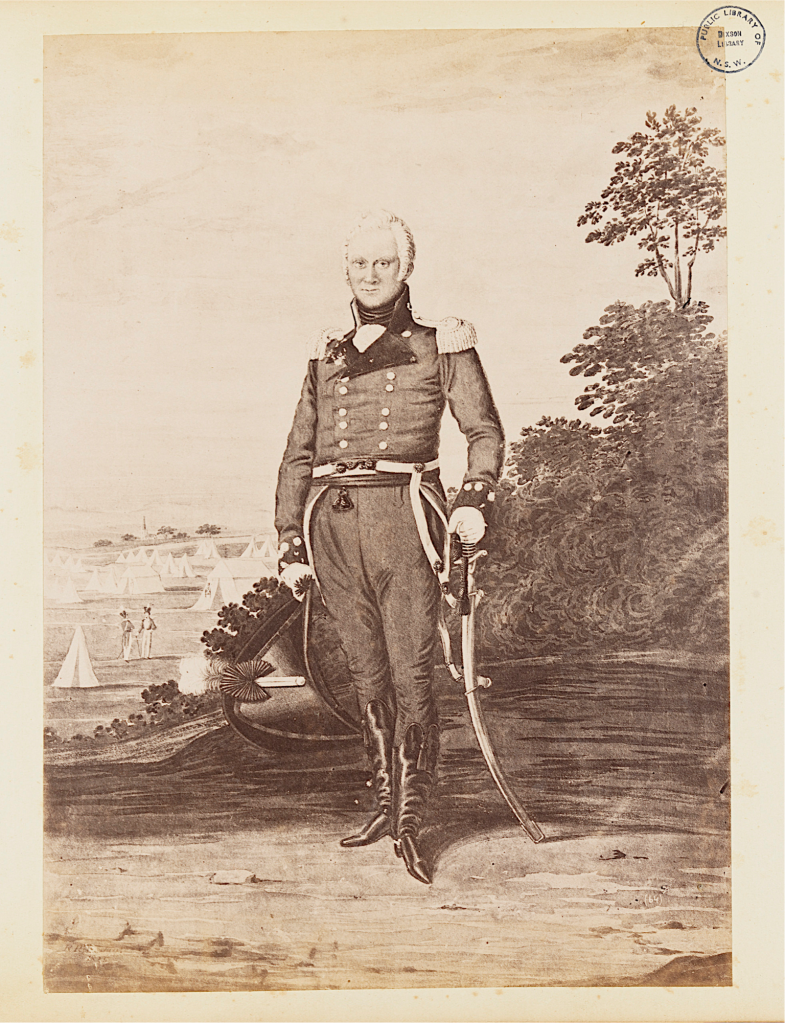

Unlike Robespierre and the carmagnole mayor, Bayly did very well during this later, Antipodean revolution. He continued as private secretary to the acting governor until Paterson, who still commanded the Corps, arrived in January 1809. Paterson had not conspired in the rebellion and wanted no part in it. He had stayed in ‘Van Diemen’s Land’ Lutruwita (Tasmania) as long as he could, begging ill health and for the officers to wait for a successor from England. When his excuses ran out, he proceeded to Cadi (Sydney), where, drinking and ailing, he let the rebels run the colony. They handed out more land in two years than King had in six: 67,000 acres.[66] This included a total of 1,070 acres at Cabramatta in Cabrogal Country to Nicholas, his wife Sarah, and three of their children. Bayly also became Naval Officer, a lucrative position collecting customs and port dues, together with a premium rental property, the naval barracks.[67]

*

Bayly must have managed his relationships well to stay in favour with the senior officers of the Corps, for he had fallen out with Macarthur. ‘Some of our old acquaintance have behaved the most scurvily,’ Macarthur wrote to his friend John Piper on Norfolk Island, just four months after the deposal:

‘Bayly, for whom every proper thing has been done, is become a violent oppositionist—the assigned reason, some information he received from Grimes about my finding fault with him; but the real one, because I would not advise Johnston to make Laycock a magistrate and police officer, with some other like disappointments respecting cows, &c.; in short, I am of opinion that, had [Bayly and the other disloyal officers] been given way to, the whole of the publick property would not have satisfied them. The result is that, although Bayly is Provost-Marshal and Private Secretary, he throws every obstacle in the way of the public business, and such a burden is thrown on me that I have not a moment to devote to my affairs or my friends’ [sic].[68]

Macarthur was embattled himself, and sailed for England the following March to give evidence at the court-martial of George Johnston. There the Major explained that if he had not deposed Bligh, a general insurrection would have erupted; the members of the court seemed to conclude that Macarthur, not Johnston, was ‘the main-spring of every thing.’[69] As a citizen, Macarthur had to be tried in the jurisdiction of his crime. Aware of a standing order for his arrest, Macarthur remained in London fully eight years until he was assured he could return home safely to his family and his sheep. The full weight of the rebellion, then, fell on Johnston, who was cashiered, and on Macarthur, in the form of a difficult exile. There was little talk of trying the other military and civilian rebels—for where, once such a process started, might it end?

Cleaning House

Meanwhile the empire was reasserting its authority over the colony. Lachlan Macquarie was appointed governor. With him travelled Ellis Bent, the new Judge-Advocate, who would inject real legal training and experience into the haphazard, and petty abuse of, due process that had characterised the rule of law in New South Wales during the Usurpation, and in milder ways since colonisation. During their stop in Rio de Janeiro they found that Johnston and Macarthur had just passed through, and that their companions, Drs. Harris and Jamison, were still in port. They talked for hours with Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie, giving the usurpers’ side of the story. Elizabeth, who would go on to have a decisive influence on the progress of the colony, noted in her journal the names that had been ‘particularly specified’ by Bligh.[70] Macarthur and ‘Nicolas Baily [sic]’ were at the top of the list; below were ‘Graham Blaxcell [sic],’ Gregory Blaxland and others. ‘Even by their own account,’ Elizabeth concluded, ‘the conduct of those persons who had acted against the Govr. was not to be justified, or even excused.’[71] The Macquaries felt particularly keenly for Johnston, who had been a close friend of Lachlan’s when they were both junior officers and would now, they imagined, face execution. Lachlan was relieved he had left the colony so that he would not be compelled to arrest him.[72]

It did fall to Macquarie to clean up the mess. He issued a proclamation outlining ‘His Majesty’s high displeasure’ at the state of affairs in the colony and reinstated Bligh for twenty-four hours to create the semblance of an orderly transition.[73] He then set about erasing the last two years. Within ten days, all court cases heard by the rebel courts were annulled, all offices reverted to those who had held them before the Usurpation, and all land grants by the acting governors were cancelled. On 10 January 1810, Bayly wrote to Macquarie explaining his case to keep his land (the particulars have not survived) and was assured that he would receive ‘every due consideration’ when the grants were considered for renewal.[74] He appears to have been successful, and entered the Macquarie decade with extensive landholdings, an apparent amnesty for past misdemeanours and high crimes, and a promising relationship with the governor.

*

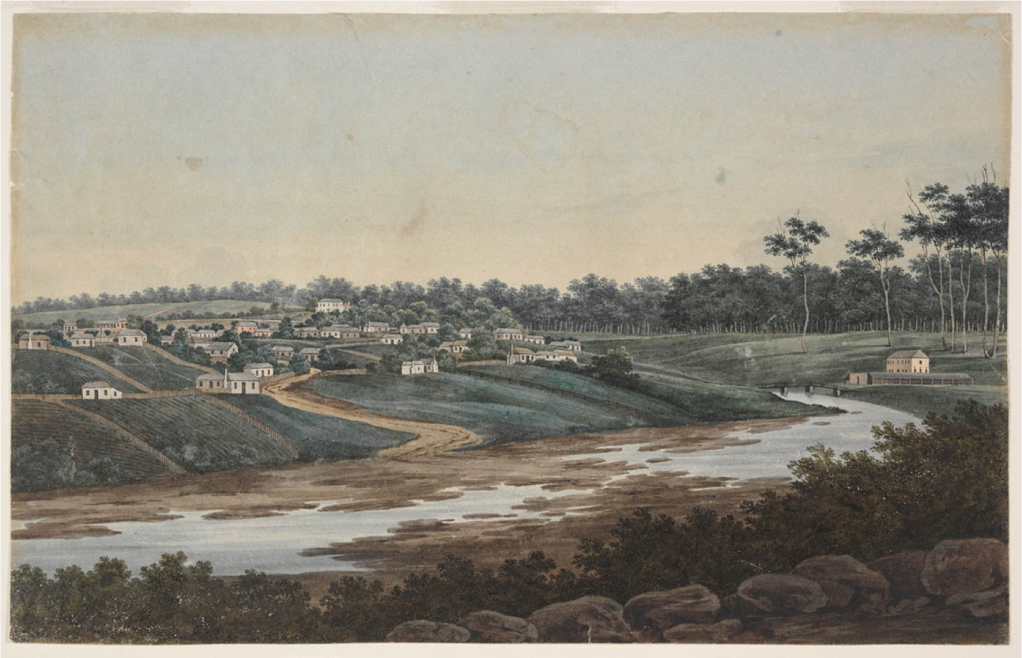

For a while, the happy period continued. Bayly was so good as to give 150 acres, in exchange for twice that in a different part of the colony, and William Bowman, John’s brother, a further 25, so that Macquarie could establish yet another township. Richmond would lie, he wrote in his diary, on ‘the most eligible and convenient spot of ground that could be found in the whole country.’[75] He was so pleased after surveying and marking out the new township that he and his wife Elizabeth returned to Bulyayorang (Windsor) and hosted a celebratory dinner for ‘a large party of friends.’[76] Charles Hook and Nicholas Bayly were appointed to the Court of Civil Judicature in March, and in June Bayly was slated for yet another grant at Bringelly in Cabrogal Country, and Hook for 700 acres at Cooke.[77]

The Final Turn of the Screw

It soon became apparent that Macquarie was not the governor that the ‘principal inhabitants’ had hoped for. In June 1812, Charles Hook, Garnham Blaxcell, Simeon Lord, Nicholas Bayly, and Gregory Blaxland petitioned the government to advance their agricultural interests. They reminded Macquarie that he had promised to take all the surplus grain from the settlers when he reduced the standing price of wheat the year prior. They also sought assurances about the price the government would pay for meat. Macquarie had the colonial secretary pen an unusually expansive response, intimating his ‘surprize [sic] and astonishment that so unfounded and unwarrantable assertion should have escaped from gentlemen in a public address of this nature.’[78] He affirmed his desire to encourage agriculture and promote prosperity, entered into some particulars about the ‘liberal’ price of meat in the prospering colony, but explained that he was responsible for the entire colonial economy. As to the last paragraph of their petition, he wanted only to express ‘his regret and displeasure at its being conceived in so assuming and dictatorial a style,’ and to say that, ‘so far from its having the effect that was probably expected on his mind’ he would continue to consider the interests of the Crown and the public, which would no doubt mean a further reduction in the price of meat and wheat paid to the producers. ‘[I]n so doing,’ Macquarie would not ‘consult the particular accommodation and convenience of a few interested individuals.’[79]

The rebuffed petition may well have been the turning point for Bayly. No doubt missing the salary and perks which had flowed to him during the Usurpation, and finding himself, perhaps, at the mercy of a governor with a frustrating commitment to other sections of the community, Bayly set himself against Macquarie as he had against King, Bligh, and Macarthur. Macquarie was plagued by the letters which flowed between the colony and the metropole—disparaging words which helped to turn his superiors in London against him—and, on 13 March 1816, Bayly wrote one such letter to Sir Henry Bunbury, Under-Secretary in the Colonial Office (where his brother, General Henry Bayly, had helped to establish connections). He began by asking for an ‘eligible situation’ on account of his eight children who were ‘entirely unprovided for’ and had become a sort of anchor, or millstone, binding him to the colony where he was ‘doomed to remain a fixture.’[80] He needed an income, a ‘situation.’ ‘There is none I should be so anxious to fill,’ he wrote, ‘as that of Colonial Secretary.’[81] The Colonial Secretary was the plum job in the colony, but the incumbent also stood with the governor at the head of the administration. It was nothing less than a call for regime change—Bayly never lacked ambition. Perhaps to stake his claim to the position of Colonial Secretary, or perhaps to help clear room for himself, Bayly then offered a series of unflattering ‘observations’ on the configuration of the colony. There was some doubt as to whether it was legal to work convicts after their arrival, since it exceeded the terms of their sentences, an argument that continued to fester, like an untreated wound, until the 1820s.[82] The regulation of convict food, clothing, and shelter was inadequate, and more had to be done to encourage their moral development, like having them attend church, instead of a general muster, of a Sunday.[83] The women were in a particularly poor position, almost as soon as they embarked on the voyage out.[84] There were more serious problems with the conduct of justice also. The week prior to composing his letter, Bayly had toured Parramatta Gaol with Reverend Samuel Marsden, the chaplain magistrate, and saw one prisoner chained to the wall, ‘perfectly mad,’ and four others withering away under a savage sentence: a year in solitary confinement on bread and water, two years in gaol, and then transportation for life to the penal settlement at Newcastle.[85] One of them, Michael Hoare, was particularly wild, and Bayly and especially Marsden decided it was produced by the conditions of his sentence and confinement. That suggestion set off a complex saga involving the magistrate, the surgeons of the gaol and the lunatic asylum, the superintendent, the governor, and the prisoner himself, over how real and feigned insanity presented, and who should make decisions about madness in a penal colony.[86]

Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State, read Bayly’s letter to the Under-Secretary and forwarded anonymised extracts to Macquarie. The charges it contained, he wrote pointedly, reflected ‘to a great degree your character and conduct in the administration of the colony.’ Macquarie found this ‘very insulting,’ as he told Elizabeth.[87] He was, after all, well aware of Bayly’s reputation regarding convicts. Bayly, Gregory and John Blaxland were known for ‘being very severe arbitrary masters and embroiled constantly in quarrels with their servants, whom,’ he noted, they ‘frequently dismiss[ed] on the most frivolous pretences.’[88] It seems Bayly, the convict beater, had remained true to his earlier form. Deeply aggrieved, Macquarie replied to the Colonial Office with a bitter letter of resignation. To this he appended a lengthy justification of his administration, and a ‘list of names, designations, &c., of persons residing at present in the colony of New South Wales, who have always manifested an opposition to the measures and administration of Governor Macquarie.’[89] At the top of the list was the chaplain, magistrate and grazier Samuel Marsden, whom he described as ‘discontented, intriguing and vindictive.’[90] The relationship between governor and chaplain had degenerated to such a point that Macquarie was confident that such a treacherous attack could only have been mounted by him. Robert Townson was listed next, but in third place was Nicholas Bayly, simply described as ‘discontented.’[91] All those listed had been in the continuous ‘habit of writing home the most gross misrepresentations.’[92] A month later, learning that Marsden had taken depositions from three free and two convict men flogged summarily by Macquarie for trespassing in the government domain, the Governor summoned the magistrate and gave full expression to his fury at the investigation, which would ‘inflame the mind of the inhabitants, excite a clamour against my government, bring my administration into disrepute, and disturb the general tranquility of the colony.’[93] He called Marsden the ‘head of a seditious low cabal’ and banned him from his presence.[94] The Secretary sent a mild response encouraging Macquarie to remain as governor, but that letter went astray. The governor grew more and more embattled, from inside the colony and beyond it, having to justify his expenses, building program, and convict policies within the colony and to London. These complaints, together with London’s interest in overhauling aspects of the administration of the colonies, meant that from 1819–21, Macquarie also had to host John Thomas Bigge while he conducted an exhausting commission of inquiry into his administration.[95] Macquarie wrote again to resign his position, and then a third time, before he learned that his resignation was accepted late in 1820.[96] Bayly had played his part in bringing down yet another governor.

Bayly was not, of course, appointed colonial secretary, nor did his influence in the colonial office produce an appointment. In January 1819, his ten-month-old daughter, Ellen, died. She was followed by her mother, Sarah, the following June, shortly after she gave birth to a tenth child that she and Nicholas named ‘Sarah Ellen.’[97]

Bad Investments

Three months after losing his wife, Bayly seemed to finally get a break when he was appointed cashier of the Bank of New South Wales. A savings bank, supported by Macquarie though not by his superiors in London, its shareholders and clientele were generally former convicts and their children, like William Redfern, D’Arcy Wentworth (a serial highwayman who opted for a transportation which was just short of criminal, and went on to be principal surgeon and superintendent of police), and the formidable businesswoman Mary Reibey, who leased the bank its premises in Macquarie Place. The ‘exclusive’ set, who had been in the habit of lending money themselves at exorbitant rates, boycotted ‘the convicts’ bank.’[98] In September 1820, the directors of the bank dismissed its cashier, Francis Williams, after discovering that he had entered imaginary deposits into the books, leaving the bank £2,000 in the lurch. Awkward letters were written to clients, and Bayly was appointed in Williams’s stead. After an audit of the sealed bags he had inherited, it appeared that there was £12,000 missing (an enormous sum relative to the £12,600 starting capital).[99] Williams had advanced money to various settlers and entered imaginary deposits in the registers to square the books, not for personal profit but to advance his social standing: it failed. Williams was transported to Newcastle for fourteen years.[100] All of this, no doubt, meant that the ‘situation’ Bayly had desired for so long must have been one of great embarrassment and anxiety.

At about a quarter to nine in the evening on Friday, 16 May 1823, twenty-year old Frances Bayly heard a gunshot, shrieked, and ran down the stairs, crying ‘Oh Lord, what is the matter!’ Thomas Loyd, the Baylys’ servant, was on his way to his master’s bedroom carrying a night candle. He ran ahead of Frances and saw Bayly’s body lying on the sofa with a pistol lying on his thigh, two or three inches from his right hand. His feet remained on the ground. Loyd, who had been with the family five years, went out and prevented Frances from entering the room.

At the coroner’s inquest the next morning, Loyd said that Bayly had been in a ‘bad state of health’ for some time and ‘very wild’ for several days, ‘from the appearance of his eyes.’[101] Dr. Thomas Stevenson, who had only just left the house, having seen Bayly at eight o’clock, agreed he had been in ‘a very disturbed state’ for some time, and ‘remarkably restless and irritable’ for two or three days.[102] His illness was of a kind that made it ‘very injurious to him to talk much’ and Stevenson had frequently recommended that he stay silent.[103] Joseph Potts, a clerk at the Bank, swore that Bayly had been ‘in quite a deranged state of mind’ for some time past, especially the day before his death, when he seemed ‘quite lost.’[104] On the day of his death he had been rambling, asking the same questions over and over and not knowing of what he was speaking. ‘Nicholas Bayley [sic] put an end to his existence by shooting himself through the head in a fit of derangement,’ the twelve jurors concluded.[105]

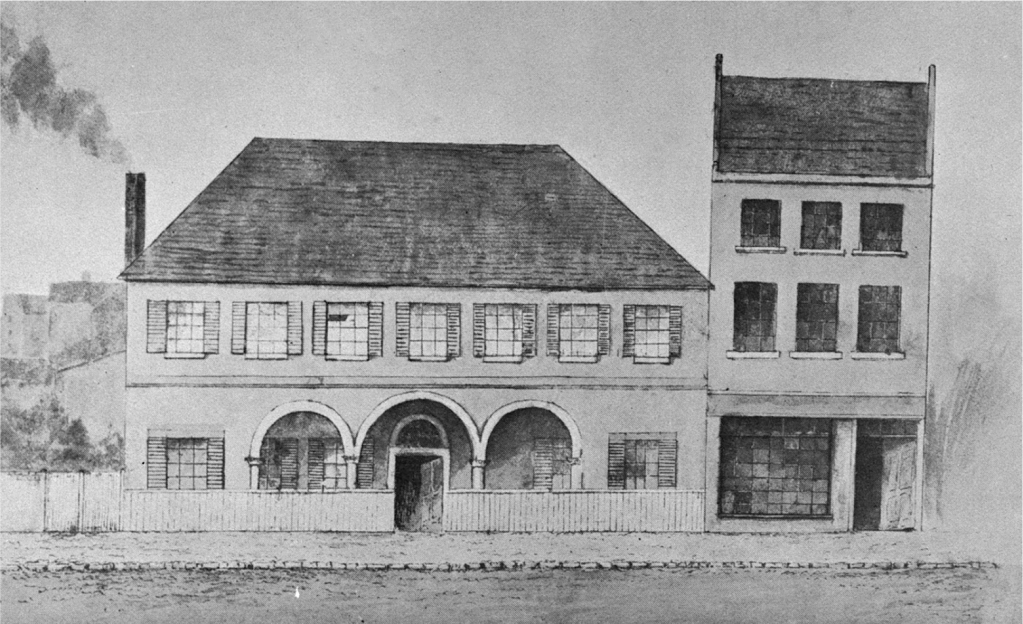

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. The Bank of New South Wales was established in 1817 in rooms rented from Mary Reibey at her Macquarie Place property, Sydney, so Bayly would have worked there for the first two years of his role as cashier. By 1822, Reibey’s house was ‘damp,’ wanting repair, and unfit for the purposes of a bank, so the Bank moved to the property depicted above, which stood opposite the Military Barracks on what was then the commercial heart of Sydney: George Street. It was at this location that Bayly took his life, and from which his hearse departed in his grand funeral procession to St. John’s Cemetery, Parramatta in 1823. Bank of New South Wales, Head 0ffice, 1822–53. Government Printing Office 1–17946 / FL1862445, State Library of New South Wales.

At 11am on Monday, 19 May 1823, the body of Nicholas Bayly was taken in a hearse from the bank building, where it seems his family lodged, to Parramatta. ‘As far as the toll-gate,’ the Gazette reported, ‘a long train of Civil and Military Officers, and other Gentlemen, followed. Several Gentlemen, we understand, proceeded all the way to Parramatta; in the church-yard of which town the body was interred in the same vault with his lately beloved wife, who died about 3 years ago, shortly after the birth of her ninth child.’[106]

* * *

Nicholas Bayly lies buried with his wife, several of his children and grandchildren, in a subterranean vault at St. John’s Cemetery, Parramatta in Burramattagal Country. The ageing stone of the vault he had had built to house his family honour, together with his illustrious connections and the social delicacies afforded to the ‘gentle,’ have protected Bayly from the ravages of time. He has been largely left in peace. A brief entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography has him a confirmed ‘malcontent,’ but leaves it there.[107]

Henry, the eldest child of Nicholas and Sarah, cared for his nine siblings after the death of his parents. After six years, he took his two brothers, Charles and Nicholas Paget, to England to finish their schooling. They returned in the following years, moved to the newly colonised land around Mudgee, and became prominent landholders and members of the community. It has been suggested that the Portuguese street names there—Douro, Madeira, Lisbon, Oporto—recall the scenes of their uncle Henry’s exploits in the Napoleonic Wars.[108] If that is true, it may have been, like Nicholas and Sarah naming their second son ‘Nicholas Paget,’ a means of strengthening the association with the successful family line.

Nicholas Bayly lived his colonial life in the shadow of John Macarthur, of whom he seems a less charismatic, less theatrical, and far less successful version. John Hunter understood that Macarthur wanted nothing less than the full power of the governor; King saw him as ‘the great perturbator’ and puppet master, with basilisk eyes, as one perfecting a system of persecution and opposition.[109] He was a man of prodigious energies to match his almost unbounded ambitions. He, like Bayly, also slipped into insanity before his death—a more protracted madness with violent delusions of persecution that took even his family from him, and left him pleading for military aid from the government that he had spent his life undermining. When Macarthur died, however, he left a thriving wool empire and a family steeped in wealth and political influence which reached around the globe. Bayly, Macarthur’s ‘adventuring needy associate’, left his eight surviving children as orphans, with £2,000 between them and a legacy of internecine violence and despair.[110]

And yet he seems worth remembering—not as a successful colonist, a ‘principal inhabitant’ of the settler colony, whatever that might mean, or as a masculinist hero of the rebellion, but as the marked anti-settler of the colony, the one who could not or would not settle.[111] Not that he was the only colonist to fail at colonisation, but he failed with a certain splendour. With every advantage imaginable, Nicholas Bayly epitomised the failure to ‘settle’ all his life, until he went, ‘restless and irritable,’ into death.[112]

Will Andrews, (L.26.Q) Bayly, Allan, Macarthur Memorial, St. John’s Cemetery, Parramatta © 2024 Will Andrews (Heritage Spatial) for St. John’s Online. Commissioned by Michaela Ann Cameron. All rights reserved. Press the play button to load the model. For instructions on how to interact further with the 3D models featured on this website, click the ? symbol that appears in the bottom right corner of each model once loaded, or see Navigation and Controls.

If this essay has raised any personal issues for you please contact: Lifeline 13 11 14 for Australian residents, or a mental health service near you.

CITE THIS

James Dunk, “Nicholas Bayly: The Anti-Settler,” St. John’s Online, (2021), https://stjohnsonline.org/bio/nicholas-bayly, accessed [insert current date]

Acknowledgements

Biographical selection, assignment, research assistance, editing & multimedia: Michaela Ann Cameron.

3D Memorial: Will Andrews (Heritage Spatial). For more, see Sensing the Dead.

References

- Matthew Allen, “Alcohol and Authority in Early New South Wales: The Symbolic Significance of the Spirit Trade, 1788–1808,” History Australia, Vol. 9, No. 3, (2012): 7–26.

- Alan Atkinson, “The Free-Born Englishman Transported: Convict Rights as a Measure of Eighteenth-Century Empire,” Past & Present, No. 144 (Aug., 1994): 88–115.

- Alan Atkinson, “The Little Revolution in New South Wales, 1808,” The International History Review, Vol. 12, No. 1 (1990): 65–75.

- Bruce Baskerville, “‘Ready at all times’: the Hawkesbury Resistance to the Rum Rebels,” History Matrix, (2013), https://historymatrix.wordpress.com/2013/08/06/ready-at-all-times-the-hawkesbury-resistance-to-the-rum-rebels/, accessed 31 October 2019.

- Anthony Bruce, The Purchase System in the British Army, 1660–1871, (London: Royal Historical Society, 1980).

- Lawrence Davoren and George Mackaness, (ed.), “A New Song, Made in New South Wales on the Rebellion,” (Sydney: D. S. Ford, 1951).

- James Dunk, Bedlam at Botany Bay, (Sydney: NewSouth, 2019).

- Ross Fitzgerald and Mark Hearn, Bligh, Macarthur and the Rum Rebellion, (Sydney: Kangaroo Press, 1988).

- B. H. Fletcher, “Bayly, Nicholas (1770–1823),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bayly-nicholas-1758/text1959, published in hardcopy 1966, accessed 13 June 2014.

- R. F. Holder, “Williams, Francis (1780–1831),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/williams-francis-2792/text3959, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed 8 November 2019.

- Max Howell and Lingyu Xie, Convicts and the Arts, (Palmer Higgs, 2013).

- David Hunt, Girt: The Unauthorised History of Australia, Volume 1, (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2013).

- Sue Jackson-Stepowski, “Yasmar,” Dictionary of Sydney, (2008), http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/yasmar, accessed 3 March 2020.

- Grace Karskens and Richard Waterhouse, “‘Too Sacred to be Taken Away’: Property, Liberty, Tyranny and the “Rum Rebellion,’” Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol. 12 (2010): [1]–22.

- N. D. McLachlan, “Macquarie, Lachlan (1762–1824),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/macquarie-lachlan-2419/text3211, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed 3 March 2020.

- Sam Paine, “Streets of Mudgee: The Portuguese Mystery, Henry Bayly and the Napoleon Link,” Mudgee Guardian, (10 April 2014), https://www.mudgeeguardian.com.au/story/2209332/streets-of-mudgee-the-portuguese-mystery-henry-bayly-and-the-napoleon-link/, accessed 31 October 2019.

- Vivienne Parsons, “Throsby, Charles (1777–1828),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/throsby-charles-2735/text3861, published in hardcopy 1967, accessed 4 November 2014.

- Margaret Steven, “Macarthur, John (1767–1834),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/macarthur-john-2390/text3153, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed 31 October 2019.

- Margaret Steven, “Hook, Charles (1762–1826),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hook-charles-2196/text2835, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed 25 October 2019.

NOTES

[1] They had been delegated by the merchants, landholders, traders, free settlers, ‘and other principal inhabitants’ of Sydney, Parramatta, the Hawkesbury and Georges River, at a public meeting which had proposed and voted on the words: “No title,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 5 January 1811, p. 4.

[2] “No title,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 5 January 1811, p. 4.

[3] For the public meeting, see “Public Advertisement,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 18 January 1812, p. 2. Similar meetings were held, and addresses drafted and voted and presented, in the Hawkesbury, Liverpool and Parramatta.

[4] “Public Advertisement,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 18 January 1812, p. 2.

[5] Michael M. Robinson, “ODE For the Queen’s Birth Day, 1812,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 18 January 1812, p. 2.

[6] Sic. Michael M. Robinson, “ODE For the Queen’s Birth Day, 1812,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 18 January 1812, p. 2.

[7] “Public Advertisement,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 18 January 1812, p. 2.

[8] R. v. John Palmer [1809] NSWKR 1; [1809] NSWSupC 1, Decisions of the Superior Courts of New South Wales, 1788–1899, (Division of Law, Macquarie University, 2011), https://www.law.mq.edu.au/research/colonial_case_law/nsw/cases/case_index/1809/r_v_palmer/#fn1, accessed 25 October 2019.

[9] Margaret Steven, “Hook, Charles (1762–1826),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hook-charles-2196/text2835, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed 25 October 2019.

[10] Blaxcell left his associate, Charles Throsby, security for a ship worth £4000. Throsby struggled through lengthy litigation before the Supreme Court found him liable for the debt. Battered by drought, the declining wool market, and poor health, he fell into a severe depression and took his own life: Ralph Darling, “Governor Darling to Right Hon. W. Huskisson, Sydney, 5 April 1828,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, Series I, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. XIV, March, 1828–May, 1829, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1922), pp. 118–19; Vivienne Parsons, “Throsby, Charles (1777–1828),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/throsby-charles-2735/text3861, published in hardcopy 1967, accessed 4 November 2014.

[11] According to family tradition, Henry was standing near the Duke of Wellington when he was hit by cannon fire, and exclaimed to the Duke “By God, Sir! I’ve lost my leg,” with the Duke replying, “By God Sir! So you have.” He was fitted with the world’s first articulated prosthetic leg, made from lime wood and leather; his own leg was buried in a miniature coffin with its own tombstone, visited by the likes of the King of Prussia and the Prince of Orange. See “The 7th Marquis of Anglesey,” The Telegraph, 15 July 2013, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/10181126/The-7th-Marquis-of-Anglesey.html, accessed 31 October 2019; “The Anglesey Leg,” National Trust Collections, http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1175888, accessed 31 October 2019.

[12] “Paget [formerly Bayly], Henry William, first marquess of Anglesey (1768–1854),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/21112, accessed 31 October 2019.

[13] Mary M. Drummond, “BAYLY, Nicholas (1749–1814), of Plas Newydd, Anglesey,” in Sir Lewis Namier and John Brooke (eds.), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1754–1790, (1964), http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1754-1790/member/bayly-nicholas-1749-1814, accessed 31 October 2019.

[14] “General Sir Henry Bayly, G. C. H.,” The Gentleman’s Magazine,26 July 1846, p. 94; Robert Burnham and Ron McGuigan,Wellington’s Brigade Commanders: Peninsula and Waterloo, (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2017), pp. 42–43.

[15] Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 1787–1868 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2004), p. 166.

[16] John Hunter, “Governor Hunter to the Duke of Portland, Sydney, New South Wales, 12 September 1798,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. II, 1797–1800, (Sydney: Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1914), p. 225, and see Elsbeth Hardie, The Passage of the Damned: What Happened to the Men and Women of the Lady Shore Mutiny, (Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2019).

[17] B. H. Fletcher, “Bayly, Nicholas (1770–1823),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bayly-nicholas-1758/text1959, published in hardcopy 1966, accessed 13 June 2014.

[18] “R. v. Bowman,” [1800] NSWKR 4; [1800] NSWSupC 4, Court of Criminal Jurisdiction Minutes of Proceedings, 1798–1800, Item: X905/473, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), also available online, “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction, Dore J.A.., 28 June 1800,” Decisions of the Superior Courts of New South Wales, 1788–1899, (Division of Law, Macquarie University, 2011), http://www.law.mq.edu.au/research/colonial_case_law/nsw/cases/case_index/1800/r_v_bowman/, accessed 31 October 2019.

[19] “R. v. Bowman,” [1800] NSWKR 4; [1800] NSWSupC 4, Court of Criminal Jurisdiction Minutes of Proceedings, 1798–1800, Item: X905/473, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), also available online, “Court of Criminal Jurisdiction, Dore J.A.., 28 June 1800,” Decisions of the Superior Courts of New South Wales, 1788–1899, (Division of Law, Macquarie University, 2011), http://www.law.mq.edu.au/research/colonial_case_law/nsw/cases/case_index/1800/r_v_bowman/, accessed 31 October 2019.

[20] Grace Karskens and Richard Waterhouse, ‘“Too Sacred to be Taken Away”: Property, Liberty, Tyranny and the “Rum Rebellion,”’ Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol. 12, (2010): 21; and see Anthony Bruce, The Purchase System in the British Army, 1660–1871, (London: Royal Historical Society, 1980).

[21] Matthew Allen, “Alcohol and Authority in Early New South Wales: The Symbolic Significance of the Spirit Trade, 1788–1808,” History Australia, Vol. 9, No. 3, (2012): 8. https://doi.org/10.2104/ha-v9n3p

[22] Matthew Allen, “Alcohol and Authority in Early New South Wales: The Symbolic Significance of the Spirit Trade, 1788–1808,” History Australia, Vol. 9, No. 3, (2012): 8. https://doi.org/10.2104/ha-v9n3p

[23] Matthew Allen, “Alcohol and Authority in Early New South Wales: The Symbolic Significance of the Spirit Trade, 1788–1808,” History Australia, Vol. 9, No. 3, (2012): 11. https://doi.org/10.2104/ha-v9n3p

[24] Philip Gidley King, “Acting-Governor King to Lieutenant-Colonel Paterson, 1 January 1802,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), pp. 459–69.

[25] Philip Gidley King, “Acting-Governor King to Lieutenant-Colonel Paterson, 1 January 1802,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), pp. 459–69.

[26] Nicholas Bayly, “Ensign Bayly to Lieutenant-Colonel Paterson, Sydney, 29 December 1801,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), pp. 458–59.

[27] Charles Morgan, “Sir Charles Morgan to Governor King, Judge-Advocate General’s Office, 11 December 1802,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), pp. 744–45.

[28] William Molesworth, Sir William Molesworth’s Speech in the House of Commons, March 6, 1838, on the State of the Colonies, (London: T. Cooper, 1, Birchin Lane, 1838), p. 27.

[29] Charles Morgan, “Sir Charles Morgan to Governor King, Judge-Advocate General’s Office, 11 December 1802,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), pp. 744–45.

[30] John Hunter, “Governor Hunter to the Duke of Portland, Sydney, New South Wales, 25 July 1798,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. II, 1797–1800, (Sydney: Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1914), p. 160.

[31] Margaret Steven, “Macarthur, John (1767–1834),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/macarthur-john-2390/text3153, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed 31 October 2019.

[32] Philip Gidley King “Acting-Governor King to Under-Secretary King, Sydney, New South Wales, 8 November 1801,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 321

[33] Philip Gidley King “Acting-Governor King to Under-Secretary King, Sydney, New South Wales, 8 November 1801,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), pp. 322–23.

[34] Philip Gidley King, “Governor King to The Duke of Portland, Sydney, New South Wales, 1 March 1802,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 457.

[35] William Gore, “Provost-Marshal Gore to Viscount Castlereagh, Cells, Sydney Jail, NSW, 27th March 1808,” in F. M. Bladen (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales: Vol. VI.—King and Bligh, 1806, 1807, 1808, (Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer, 1898), p. 553.

[36] Philip Gidley King, “Governor King to The Duke of Portland, Sydney, New South Wales, 1 March 1802,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. III, 1801–1802, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 457.

[37] Sic. Seditious Anonymous Papers, with remarks thereon, enclosure in Philip Gidley King, “Governor King to Lord Hobart, Sydney, New South Wales, 9 May 1803,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IV, 1803–June, 1804, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 164.

[38] Philip Gidley King, “Governor King to Lord Hobart, Sydney, New South Wales, 9 May 1803,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IV, 1803–June, 1804, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), pp. 158–59.

[39] “General Sir Henry Bayly, G. C. H.,” The Gentleman’s Magazine, 26 July 1846, p. 94.

[40] Philip Gidley King, “Governor King to Lord Hobart, Sydney, New South Wales, 9 May 1803,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IV, 1803–June, 1804, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 164.

[41] Charles Morgan, “Sir Charles Morgan to Governor King, 4 January 1804,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IV, 1803–June, 1804, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 452.

[42] “[Enclosure No. 7]: Government and General Orders, 8 March 1803,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IV, 1803–June, 1804, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 335; Philip Gidley King, “Governor King to Sir Charles Morgan, Sydney, N. S. Wales, 9 May 1803,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IV, 1803–June, 1804, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 267.

[43] Charles Morgan, “Sir Charles Morgan to Governor King, 4 January 1804,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IV, 1803–June, 1804, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1915), p. 453.

[44] “Augt 9 [1803], Mr. Nich.s Bayley, District of Petersham, 480 acres, granted by Governor King, Consolidated grant,” Colonial Secretary: List of all Grants and Leases 1788–1809, Reel: 1999; Series: NRS 1213, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, NSW, Australia).

[45] Sue Jackson-Stepowski, “Yasmar,” Dictionary of Sydney, (2008), http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/yasmar, accessed 3 March 2020.

[46] “General Orders,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 30 March 1806, p. 1.

[47] On the rebellion, see Ross Fitzgerald and Mark Hearn, Bligh, Macarthur and the Rum Rebellion (Kenthurst, NSW: Kangaroo Press, 1988); Alan Atkinson, “The Little Revolution in New South Wales, 1808,” The International History Review, Vol. 12, No. 1, (1990): 65–75; Grace Karskens and Richard Waterhouse, “‘Too Sacred to Be Taken Away’: Property, Liberty, Tyranny and the ‘Rum Rebellion,’” Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol. 12, (2010): 1–22; James Dunk, Bedlam at Botany Bay, (Sydney: NewSouth, 2019), pp. 180–209.

[48] Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. VI, August, 1806–December, 1806, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1916), p. xxiv.

[49] John Palmer, “Commissary Palmer to the Secretaries to the Treasury, Sydney, New South Wales, 29 April 1808,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. VI, August, 1806–December, 1806, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1916), p. 614.

[50] “J. T. Campbell to Nicholas Bayly,” Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence, Item: 4/3490B; Reel 6002, pp. 77–78, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia).

John Palmer, “Commissary Palmer to the Secretaries to the Treasury, Sydney, New South Wales, 29 April 1808,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. VI, August, 1806–December, 1806, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1916), p. 614.

[52] James Dunk, “Authority and the Treatment of the Insane at Castle Hill Asylum, 1811–1825,” Incarceration, Migration, Dispossession and Discovery: Medicine in Colonial Australia, special issue of Health and History, Vol. 19, No. 2,(2017): 17–40. https://doi.org/10.5401/healthhist.19.2.0017.

[53] English counsel, quoted in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. VI, August, 1806–December, 1806, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1916), p. xxvi.

[54] Settlers’ memorial to Viscount Castlereagh, 17 February 1809, in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. VII, January, 1809–June, 1813, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1916), p. 149.

[55] “Settlers’ memorial to Viscount Castlereagh, 17 February 1809,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. VII, January, 1809–June, 1813, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1916), p. 149. One signee was William Bowman, John’s brother, who he had encouraged to migrate to the colony.

[56] Bruce Baskerville has written at length about the resistance to the rebels offered by the Hawkesbury settlers, and the flag sewn by the women of the Bowman family used as a symbol of that resistance: “‘Ready at all times’: The Hawkesbury Resistance to the Rum Rebels,” History Matrix, (2013), https://historymatrix.wordpress.com/2013/08/06/ready-at-all-times-the-hawkesbury-resistance-to-the-rum-rebels/, accessed 31 October 2019.

[57] “Classified Advertising,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 26 March 1809, p. 2.

[58] “Classified Advertising,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 27 August 1809, p. 1; “Classified Advertising,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 10 September 1809, p. 2; “Classified Advertising,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 22 October 1809, p. 2; “Classified Advertising,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Sunday 5 November 1809, p. 1.

[59] The song was circulated anonymously, and an unattributed copy included in Bligh’s collected papers relating to the Rebellion. See Max Howell and Lingyu Xie, Convicts and the Arts, (Palmer Higgs, 2013); Lawrence Davoren and George Mackaness, (ed.), “A New Song, Made in New South Wales on the Rebellion,” (Sydney: D. S. Ford, 1951).

[60] Lawrence Davoren and George Mackaness, (ed.), “A New Song, Made in New South Wales on the Rebellion,” (Sydney: D. S. Ford, 1951).

[61] Max Howell and Lingyu Xie, Convicts and the Arts, (Palmer Higgs, 2013); Lawrence Davoren and George Mackaness, (ed.), “A New Song, Made in New South Wales on the Rebellion,” (Sydney: D. S. Ford, 1951).

[62] Max Howell and Lingyu Xie, Convicts and the Arts, (Palmer Higgs, 2013); Lawrence Davoren and George Mackaness, (ed.), “A New Song, Made in New South Wales on the Rebellion,” (Sydney: D. S. Ford, 1951).

[63] Lawrence Davoren and George Mackaness, (ed.), “A New Song, Made in New South Wales on the Rebellion,” (Sydney: D. S. Ford, 1951).

[64] William Bligh, “Governor Bligh to Viscount Castlereagh, Government House, Sydney, New South Wales, 30 April 1808,” in F. M. Bladen (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales: Vol. VI.—King and Bligh, 1806, 1807, 1808, (Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer, 1898), p. 623.

[65] William Bligh, “Governor Bligh to Viscount Castlereagh, Government House, Sydney, New South Wales, 30 April 1808,” in F. M. Bladen (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales: Vol. VI.—King and Bligh, 1806, 1807, 1808, (Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer, 1898), p. 623.

[66] David S. Macmillan, “Paterson, William (1755–1810),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/paterson-william-2541/text3455, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed 4 November 2019.

[67] B. H. Fletcher, “Bayly, Nicholas (1770–1823),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bayly-nicholas-1758/text1959, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed 3 March 2020.

[68] John Macarthur, “John Macarthur to Captain Piper, Sydney, 24 May 1808,” in F. M. Bladen (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales: Vol. VI.—King and Bligh, 1806, 1807, 1808, (Sydney: William Applegate Gullick, Government Printer, 1898), p. 643.

[69] John Ritchie, (ed.), A Charge of Mutiny: The Court Martial of Colonel George Johnston for Deposing Governor William Bligh in the Rebellion of 26 January 1808, (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1988), p. 90.

[70] Elizabeth Macquarie, “23 August–23 September 1809,” in Elizabeth Macquarie, Journal of a Voyage from England to Sydney in the ship ‘Dromedary,’ 15 May 1809–25 December 1809, (1809), SAFE/C 126 (Safe 1/303), C 126 (Safe 1 / 303) / FL418035– FL418036, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales., , transcribed at Journeys in Time, https://www.mq.edu.au/macquarie-archive/journeys/1809/1809a/aug23.html, accessed 5 November 2019.

[71] Elizabeth Macquarie, “23 August–23 September 1809,” in Elizabeth Macquarie, Journal of a Voyage from England to Sydney in the ship ‘Dromedary,’ 15 May 1809–25 December 1809, (1809), SAFE/C 126 (Safe 1/303), C 126 (Safe 1 / 303) / FL418035– FL418036, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales., , transcribed at Journeys in Time, https://www.mq.edu.au/macquarie-archive/journeys/1809/1809a/aug23.html, accessed 5 November 2019.

[72] Elizabeth Macquarie, “23 August–23 September 1809,” in Elizabeth Macquarie, Journal of a Voyage from England to Sydney in the ship ‘Dromedary,’ 15 May 1809–25 December 1809, (1809), SAFE/C 126 (Safe 1/303), C 126 (Safe 1 / 303) / FL418035– FL418036, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales., , transcribed at Journeys in Time, https://www.mq.edu.au/macquarie-archive/journeys/1809/1809a/aug23.html, accessed 5 November 2019.

[73] Lachlan Macquarie, “Proclamation by Lachlan Macquarie reinstating William Bligh as Governor for twenty four hours, after which Macquarie will assume command, 1 January 1810,” (Sydney: George Howe, Gov.t printer, 1810), New South Wales. Governor – General Orders and Proclamations [printed broadsides], 1800–1810, Safe 1/87 / FL1145788, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

[74] “J. T. Campbell to Nicholas Bayly, 10 January 1810,” Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence, Item: 4/3490B; Reel: 6002, p. 15, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia).

[75] Lachlan Macquarie, Memoranda and Letters. 22 December 1808–14 July 1823, SAFE/A772 (Safe 1/359), 29f; Reel CY301; Frame 36, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, transcribed at https://www.mq.edu.au/macquarie-archive/lema/1811/1811jan.html, accessed 15 October 2019.

[76] Lachlan Macquarie, Memoranda and Letters. 22 December 1808–14 July 1823, SAFE/A772 (Safe 1/359), 29f; Reel CY301; Frame 36, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, transcribed at https://www.mq.edu.au/macquarie-archive/lema/1811/1811jan.html, accessed 15 October 2019.

[77] “Government and General Orders,” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 30 March 1811, p. 2; “On list of persons to receive grants of land in different parts of the Colony as soon as they can be measured at Bringelly,” Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence, Item: 9/2652, Fiche 3266, p. 6, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia).

[78] “J. T. Campbell to Messrs. Hook, Blaxcell, Lord, Bayly, and Gregory Blaxland, under cover to C. Hook Esq., 23 June 1812,” Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence, Series: 935; Item: 4/3491; Reel 6002 (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), pp. 278–81.

[79] “J. T. Campbell to Messrs. Hook, Blaxcell, Lord, Bayly, and Gregory Blaxland, under cover to C. Hook Esq., 23 June 1812,” Colonial Secretary’s Correspondence, Series: 935; Item: 4/3491; Reel 6002, (State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia), pp. 278–81.

[80] Nicholas Bayly, “Nicholas Bayly to Sir H. E. Bunbury, Bayly Park, New South Wales, 13 March 1816,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IX, January, 1816–December, 1818, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1917), pp. 856–58.

[81] Nicholas Bayly, “Nicholas Bayly to Sir H. E. Bunbury, Bayly Park, New South Wales, 13 March 1816,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IX, January, 1816–December, 1818, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1917), pp. 856–58.

[82] Alan Atkinson, “The Free-Born Englishman Transported: Convict Rights as a Measure of Eighteenth-Century Empire,” Past & Present, No. 144, (Aug., 1994): 88–115.

[83] Nicholas Bayly, “Nicholas Bayly to Sir H. E. Bunbury, Bayly Park, New South Wales, 13 March 1816,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IX, January, 1816–December, 1818, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1917), pp. 198–200.

[84] Nicholas Bayly, “Nicholas Bayly to Sir H. E. Bunbury, Bayly Park, New South Wales, 13 March 1816,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IX, January, 1816–December, 1818, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1917), pp. 199–200.

[85] Nicholas Bayly, “Nicholas Bayly to Sir H. E. Bunbury, Bayly Park, New South Wales, 13 March 1816,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IX, January, 1816–December, 1818, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1917), p. 200.

[86] See James Dunk, Bedlam at Botany Bay, (Sydney: NewSouth, 2019), pp. 127–38.

[87] Elizabeth Macquarie, “Elizabeth Macquarie to James Drummond, 12 December 1817,” Lachlan Macquarie Papers, 1787–1824, CY 306 (A797, Safe 1/382–391), p. 135, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

[88] Lachlan Macquarie “Governor Macquarie to Earl Bathurst, Government House, Sydney, New South Wales, 4 December 1817,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IX, January, 1816–December, 1818, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1917), p. 509.

[89] [Enclosure] “List of the Names, Designations, &c., of Persons residing at present in the Colony of New South Wales, who have always manifested an Opposition to the Measures and Administration of Governor Macquarie,” in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia, SeriesI, Governors’ Despatches to and from England, Vol. IX, January, 1816–December, 1818, (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1917), p. 500.